Early Indigenous Americans relied heavily on meat from mammoths to survive, according to a new study, which suggests they were top-notch experts at hunting the massive beasts.

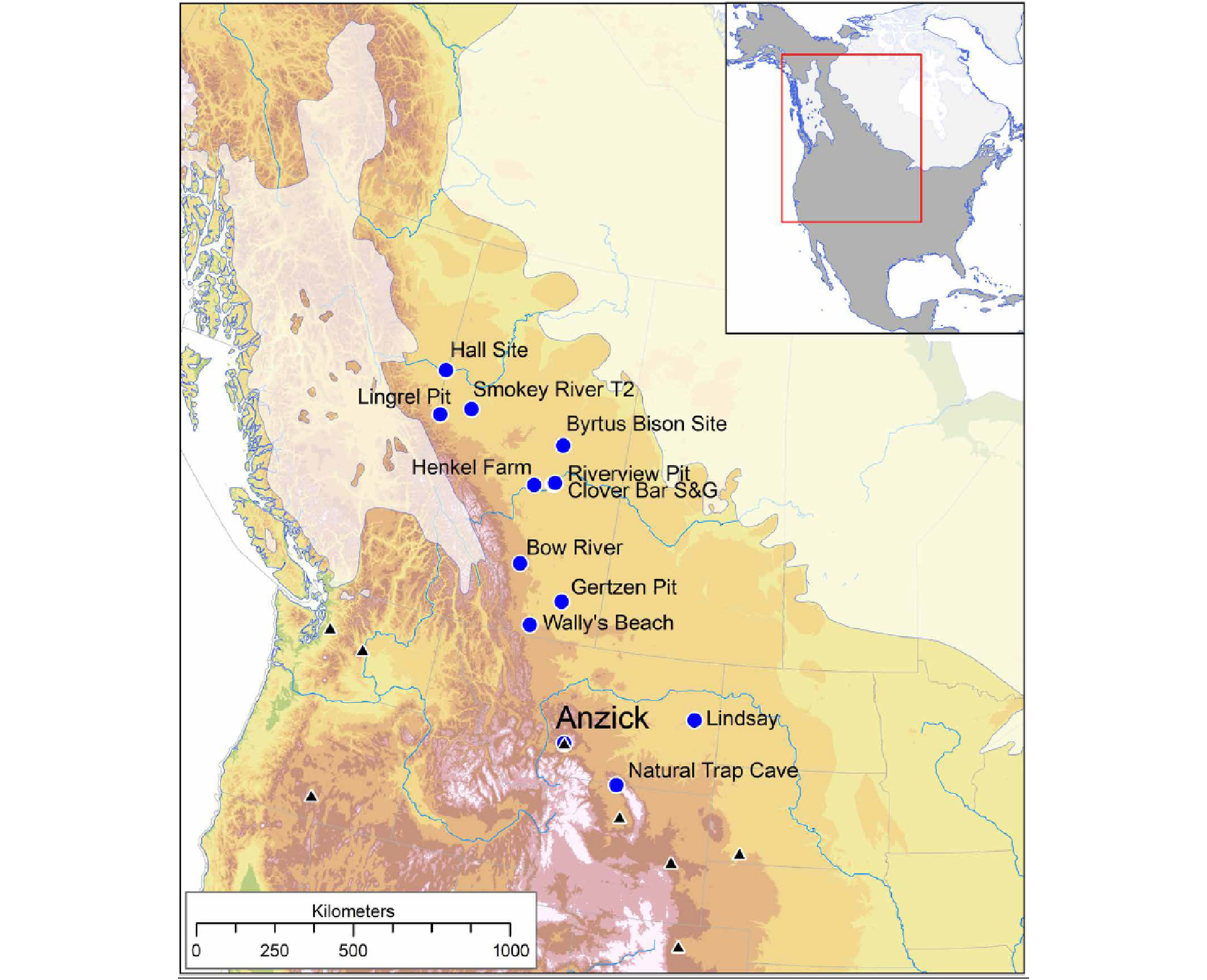

The findings, reported in a study published Wednesday (Dec. 4) in the journal Science Advances, are based on chemical analyses of the bones of an 18-month-old boy — dubbed Anzick-1 — who lived almost 13,000 years ago in what is now Montana.

The boy was probably still breast-feeding, and the results reveal that the diet of his mother was "closest to that of [the now-extinct] scimitar cat, a mammoth specialist," the researchers wrote in the study.

To investigate the diet of the boy's mother, the team looked at stable radioisotopes — atoms of an element that have a different number of neutrons in their nuclei — in the boy's bones. The technique measures the distinctive abundance of specific radioisotopes, which can be used to reconstruct the diet of an ancient person.

The boy's "isotopic fingerprint" was probably inherited directly from his mother and showed that mammoths were an important source of food for his entire family group, the authors wrote in the study.

That, in turn, suggests that people from the Western Clovis culture, to which the boy belonged, were regularly hunting mammoths — and to a lesser extent elk (Cervus canadensis), bison (Bison bison and B. antiquus) and a now-extinct genus of camel (Camelops).

The results are direct evidence of Western Clovis diets about 12,800 years ago, showing they preferred the meat of mammoths (mainly Mammuthus columbi) above all other sources — contrary to theories they mainly hunted smaller game, the authors wrote in the paper.

"These data suggest that Western Clovis people … were more focused on larger-bodied megafauna grazers, primarily Mammuthus [mammoths], and were not generalists who regularly consumed smaller-bodied herbivores," the authors wrote in the study.

Ancient Americans

The Clovis people lived in North America between about 13,000 and 12,700 years ago. They were once thought to have been the earliest humans in North America, but recent studies suggest the first Americans arrived even earlier, possibly around 23,000 years ago.

Mammoths also roamed the Americas at that time and migrated for long distances, making them a reliable source of fat and protein for early humans, the authors wrote.

"The focus on mammoths helps explain how Clovis people could spread throughout North America and into South America in just a few hundred years," co-lead author of the study, James Chatters, an archaeologist and paleontologist at McMaster University in Canada, said in a statement.

Co-lead author Ben Potter, an archaeologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, added that the results of the study confirmed what had been found at other archaeological sites. He said that hunting mammoths provided a flexible way of life and allowed the Clovis people to move into new areas without having to rely on smaller game animals, which could vary from one region to the next.

"This mobility aligns with what we see in Clovis technology and settlement patterns," Potter said in the statement. "They were highly mobile."

The new study modeled the diets of Clovis people by analyzing previously-published isotopic data from Anzick-1, and then adjusting it for nursing to estimate the isotopic values of his mother's diet.

The resulting isotopic fingerprint showed that about 40% of her diet came from mammoth meat, while other large animals like elk and bison made up most of the rest.

The results also show that small mammals played a very minor role in the ancient woman's diet, contrary to ideas that they may have been an important food source. The authors also suggest that the Clovis preference for mammoth meat may have played a part in the demise of these giant beasts in the Americas toward the end of the last ice age.