When the Liberal Party’s most senior right-wing figure, Peter Dutton, forced a leadership spill in 2018, ending Malcolm Turnbull’s premiership, even some moderates in the party room preferred him over the hyper-ambitious Scott Morrison. Yet it was to the latter they reluctantly turned, judging him less frightening to voters.

That calculation paid off handsomely with Morrison’s almost lone-hand “miracle” win in the 2019 general election.

Four years later though, after the religious and secretive Morrison had steered the party into its current trench, Liberals unanimously decided there was no viable alternative to Dutton as leader after all.

Many on the Labor side were delighted, viewing Dutton as essentially unelectable, citing his bullish fear-mongering over African gangs, Chinese drums of war, and asylum-seekers.

The decision to install, unopposed, a largely unpopular right-wing leader after Australian voters had just shifted to the left and towards female candidates, speaks to an entirely different calculation being made by Liberals about their leadership in 2022.

Read more: Did Australia just make a move to the left?

Where Morrison had been considered more sellable, by 2022, Dutton’s image problem with young people, cosmopolitans, and particularly with women, hardly mattered.

It was not his ability to win seats three years hence that was paramount in their minds, but the Queenslander’s bona fides as a native conservative speaker capable of holding the centre-right parties together after their electoral drubbing.

Put simply, the fact that Dutton is from Queensland, is well-liked internally, and moreover is trusted, meant he offered the best chance of steadying a party banished from office and adrift from its core values of small government and fiscal restraint.

It is against this largely existential metric in the early months of an ascendant Labor government that Dutton’s preferment is best understood.

Of course, from Dutton’s point of view, he wants to do both – hold his beleaguered show together and then win back voters by putting Labor under such extreme pressure that he might ultimately become prime minister.

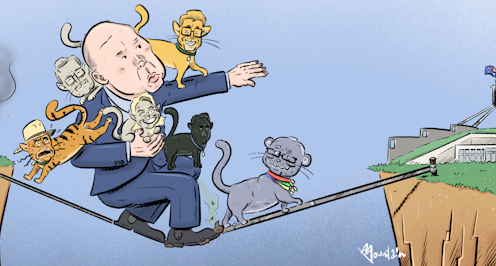

Right now though, these objectives are pulling him (and them) in different directions.

Published opinion polls such as Resolve Monitor and Newspoll suggest voters saw little in Dutton’s ascension to reassure them that the former government imbibed their stern message through the ballot box.

Read more: Labor extends big lead in Newspoll, but Morgan is much better for Coalition

Yet Dutton remains unchallenged in his leadership and committed to his course. So far, there has been no moderate repositioning.

Despite a key take-out from the election being the defeat of several prominent Liberal men in “safe seats” at the hands of strong female independent candidates, it was left to Dutton’s deputy leader Sussan Ley to acknowledge the Liberal Party’s need to do better on women’s issues.

Neither was there any acceptance that the Coalition’s decade-long assault on climate science had been a political and policy disaster, damaging Australia’s reputation and driving voters across the country towards pro-climate action candidates.

True to his image, Dutton offered no real contrition or apology, no reflection on the electorate’s judgement, and no white flag.

The reason for this bullish stance, underlined by refusing to support the 43% 2030 target in legislation? In two words, Coalition unity.

Presumably, Dutton knows that retreating on climate would weaken a distinct electoral advantage now enjoyed by Labor, while also helping to soften his “hard man” image into the bargain.

Yet the fear is that certain Nationals and even some hard-line Liberals, would rebel and perhaps even break away if the Coalition parties were to go green. Defections to Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, and from the Liberals to the Nationals, are thought possible.

As one party insider and Dutton admirer told me, “Peter can’t guarantee a win at the next election from here but he can pretty much lock in a loss if the centre-right fractures or goes to war with itself”.

Yet Dutton faces a critical dilemma. Self-evidently, playing hard-ball to hold his forces together in defeat takes him further away from the disaffected Liberal voters he needs to win back to be competitive.

Boycotting the recent jobs and skills or “union” summit as he dubbed it, while decrying attendees as union “thugs”, seems straight out of the high-impact/maximum aggression playbook used by Tony Abbott.

Does Dutton seriously hold the view that this tactic can work again in the greener and more feminised politics of the 2020s – especially against a unified Labor government?

For him, reaching the requisite 76 seats in the 151-seat House of Representatives without retaking some or all of the previously “safe” electorates lost to so-called “teal” independents in 2022 is a mammoth task. It could even see further metropolitan losses to highly credentialed independents.

And yet retaking these electorates without a decisive step to the middle-ground on key issues such as climate, women’s representation, corruption/parliamentary integrity, and the Uluru agenda, seems equally unlikely.

However, according to one school of thought, Dutton has made all the right calls.

On emissions, former minister and fellow Queensland senator, George Brandis, has argued Dutton should ignore current public opinion, and presumably the national interest (or even what is right) and hope that soaring energy and living costs remain sufficiently salient at the next election to drive voters back to the Coalition. Again, this is right out of the Abbott playbook.

This might play well in the base but risks further shredding the Liberal Party’s standing in middle Australia – especially as younger voters enter the electoral roll. Is it worth the reputational damage?

It is well known in Australian politics that opposition leaders appointed in the wake of removal from office almost never become prime minister. Some don’t even get the chance to contest an election.

The last example federally was in the 1910s.

This is hardly surprising when you consider that the most recent single-term government federally was Labor’s James Scullin 1929-32. Thirty-two, by the way, was also the unemployment rate, whereas currently it is closer to 3%.

Strategically, Dutton is right to prioritise his own survival, given that opposition leaders are more vulnerable to their own party rooms than they are to voters.

But he must also lead in a way that provides his colleagues with a realistic belief that government is attainable. This is where greater electoral sensitivity might be useful.

While new governments are invariably re-elected, what is less appreciated is that they also tend to lose seats at their first return to the ballot box. Think Bob Hawke in 1984, John Howard in 1998, Kevin Rudd/Julia Gillard in 2010 and Tony Abbott/Malcolm Turnbull in 2016.

Anthony Albanese’s two-seat majority would be easily obliterated by the seat losses sustained by each of these prime ministers facing their first elections as incumbents.

So the question for Dutton is, does aggressive partisanship on climate, women, and the other issues, really offer the best hope for regaining Australia’s centre-ground in 2025?

An alternative course would be to use his conservative credibility with his colleagues to affect a modernisation along similar lines to those of the broader population.

Call it the difference between being a leader or merely a cheerleader.

Mark Kenny does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.