The Dutch government formally apologised last week for its role in “systematic and extreme violence” during Indonesia’s fight for independence from Dutch colonial rule between 1945 and 1949.

The apology overturns the official Dutch government position since the last state-sponsored inquiry in 1969. That inquiry held that Dutch military “excesses” during the Indonesian National Revolution had been irregular and exceptional.

The Dutch government based the official apology on Dutch and Indonesian historians’ findings. Their project was funded by the Dutch government through three Dutch research institutes.

The historians conclude that Dutch leaders in the late 1940s enabled extreme violence by fostering conditions of impunity for military perpetrators. Their atrocities went largely unpunished. The researchers were careful to emphasise the findings lay no blame on individual soldiers.

Yet Dutch soldiers’ own records – especially amateur photographs, many thousands of which survive – have long contained evidence of atrocities. They also recorded other kinds of violence that have yet to receive proper attention.

My research has shown these personal photographs were not like secret diaries. Soldiers copied and shared them. They were even sometimes used by military authorities.

Photographs are an important part of the story

Photographs were sometimes the only records left by Dutch servicemen. They were an outlet for wartime experiences that soldiers omitted from official reports.

The photographs provide “off-the-record” evidence of atrocities, such as the summary execution of Indonesian combatants and civilians.

They also provide views of violence the Dutch considered acceptable, like the punitive torching of villages and heavy artillery fire on civilian targets.

Such photographs also routinely show the patrols during which Indonesians were arbitrarily detained, intimidated and tortured.

These photographs were part of war memories that may well have been kept from newspaper journalists, Dutch bureaucrats or even veterans’ children, but they circulated among particular groups.

Their concealment and “forgetting” has been part of a broader social and political phenomenon, enabled by the lack of official will to confront the war or the longer history of Dutch colonialism in Indonesia.

Another version of history

As late as the 1990s, Dutch veterans’ books were still using soldier photographs from the 1940s to illustrate the myth of the military actions as a peace-keeping mission rather than a war.

Military leaders like General Simon Spoor, chief of staff of the Dutch national and colonial armies fighting in Indonesia, directed the image of humanitarian intervention. It was also the self-perception of tens of thousands of Dutch volunteers and conscripts deployed with national forces from 1946.

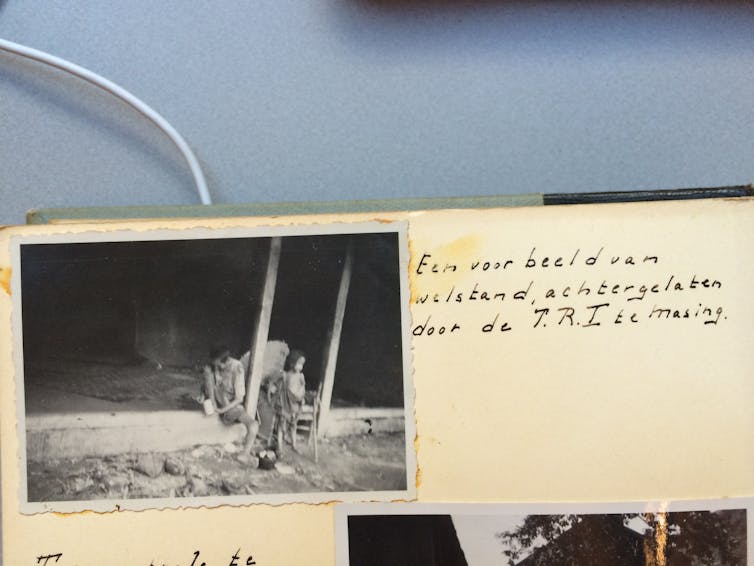

Their photographs portray outrage and dismay at Indonesian civilians suffering from malnutrition and disease. They attributed this to the neglect of militant “terrorists” – rather than the effects of the recent Japanese occupation (1942– 1945) or, indeed, the Dutch blockades that stopped supplies from reaching Republican-held areas.

Cameras also captured the reality of violence by Indonesians

Soldiers’ cameras also recorded atrocities committed by Indonesians.

These remain a complex and sensitive topic, as demonstrated by recent controversy over the use of the term “bersiap” to remember Indo-European victims of violence in the Rijksmuseum exhibition, Revolusi!.

In Indonesia, recent artistic and community work to recognise the persecution of Chinese Indonesians during the revolution reconsiders the long history of ethnic violence and its troubled role in a struggle that was, at times, as much about conflicting visions of a nation and who would be included in it as it was a fight against colonialism.

My research suggests Dutch soldiers’ photographs raise questions about what it took for vulnerable Indonesian civilians to survive a conflict that followed right after the serious deprivations of the Japanese occupation.

Indonesian women, for example, sometimes worked as domestic servants and provided companionship and sex for Dutch soldiers. The soldiers’ photographs typically romanticise a transaction that, for the women, was a way to earn a living.

Soldiers’ records show a situation fraught with danger for these women. They could be treated with contempt and suspicion in a militarised environment where rape and sexual coercion frequently went unpunished.

Dutch soldiers’ photographs, therefore, provide glimpses of Indonesians overlooked in debates over who gets remembered as a hero, victim or perpetrator in war commemorations, both in the Netherlands and Indonesia.

Susie Protschky menerima dana dari Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.