An analysis of over 4,000 stone artifacts discovered on an island off northwestern Australia provides a snapshot of Aboriginal life tens of thousands of years ago.

The discovery underscores the "long-term connections" that Indigenous peoples have to modern-day Australia, said David Zeanah, an anthropologist at California State University, Sacramento and lead author of a new study describing the analysis.

The diverse artifacts found on the island also reveal intriguing insights about the movement of people between Australia's mainland and the island, especially during the peak of the last ice age, between 29,000 and 19,000 years ago, according to the study, which was published April 1 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

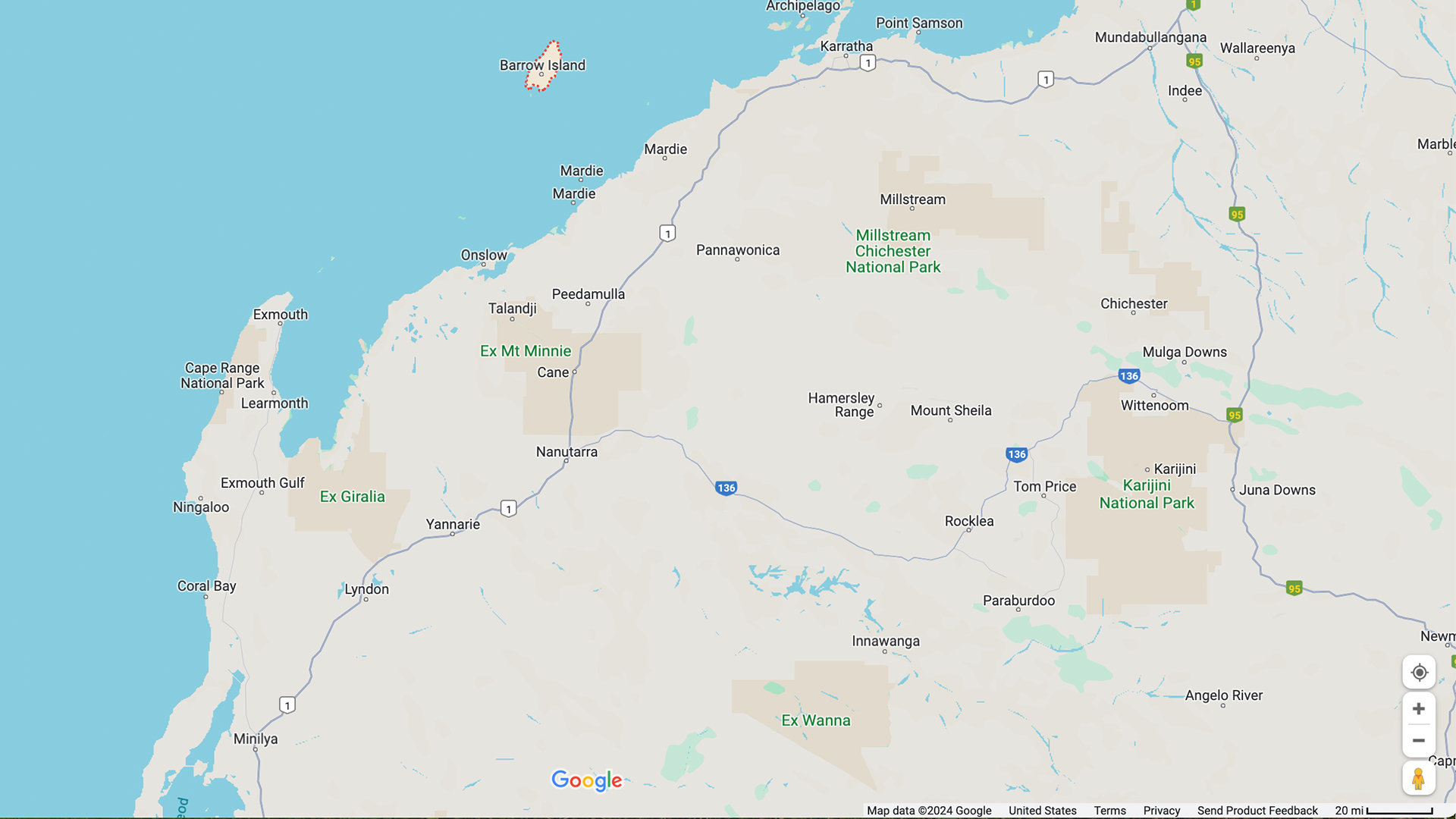

At that time, sea levels were low enough to expose the continental shelf between Australia and what is now Barrow Island, a 78-square-mile (202 square kilometers) territory about 37 miles (60 km) off Australia's northwest coast. Thousands of years ago, it would have formed the high plateau of a vast, continuous plain spanning over 4,200 square miles (10,800 square km), Zeanah told Live Science.

Archaeologists already knew that people once lived on the island, thanks mainly to a trove of archaeological evidence left behind in rock shelters — most famously, in one called Boodie Cave. But for the new research, the scientists looked beyond the island's caves to explore several open-air deposits scattered across Barrow Island.

Over three years, they examined 4,400 slicing, cutting and grinding tools from a mix of sites. What surprised the researchers was the variety in the artifacts' compositions. Most of the tools found in caves were fashioned out of limestone, the most abundant geological material on the island. Those discovered at the open-air sites, by contrast, were made mostly from rocks, including igneous and sandstone, that matched sources on mainland Australia.

The findings show "a surprising amount of diversity in stone tool composition over a relatively small area," said Tiina Manne, an archaeologist at The University of Queensland in Australia who was not involved in the research.

This diversity is significant because it reveals details about the people who frequented Barrow Island, Zeanah said.

"The open sites provide clear links to the mainland geologies, and that infers that people were using the coastal plain that's underwater now," Zeanah said. An example he found particularly intriguing was the roundish, flat grinding stones that are derived from geological sources beyond Barrow Island. The team discovered that these stones were water-worn, suggesting that before they were crafted into grinding tools, they had been hand-selected from stream beds or tidal regions, perhaps from coastal flats or rivers that may have run across the exposed plain that once connected Barrow Island to mainland Australia when sea levels were low.

The indication that many of the island's tools came from far-flung locations is exciting, Zeanah said, as it suggests that the ancient exposed plain may have been a thoroughfare for trade and exchange between different groups.

"This was probably not like a single group of people moving seasonally across the plains," Zeanah said. "The area is vast. The materials may have been transmitted by trade, or by Aboriginal people going from group to group. So that implies a social network."

The presence of those grinding stones on Barrow Island supports the idea that mass movement and knowledge sharing unfolded for thousands of years across this landscape, the study authors said.

"What that suggests to us is that people knew that there wasn't good stone on Barrow Island, and they often brought cobbles to provision the landscape there, so that they could revisit in the future," Zeanah said. "That shows a lot of logistics, foresight and knowing the landscape well, I believe."

The researchers are unsure why the geological makeup of the cave tools differs from those found outside. The most likely explanation is that artifacts made of limestone do not survive exposure on the surface as well as artifacts made of harder stone from the mainland. Another possibility has to do with how sea levels rose as the ice age declined, which would have gradually severed Barrow Island from the mainland and constricted the movement of people across the plain. In Boodie Cave, only a handful of unearthed tools were made of rocks that originated elsewhere. And in the protected cave environment, it has been possible to show that those tools tend to be older, and therefore may have been deposited earlier, when sea levels were at their lowest.

Therefore, it's likely that these remote tools were brought to the site by groups that could move freely between Barrow Island and the mainland. Limestone tools were used more intensively when rising sea levels began to cut-off the island from the mainland, the study authors said. This separation would have driven the islands' inhabitants to settle in caves and rely on the abundant local limestone to make the tools, the researchers suggested.

Thalanyji people, representatives of whom co-authored the study with Zeanah and colleagues, note there are oral histories about the islands on their sea country. Zeanah hopes this new research will help to highlight these ancient connections.

The study is "absolutely unique in Australia," Manne said. "It provides a record of coastal and hinterland desert landscape use by Aboriginal peoples during a time period that is virtually unknown from elsewhere on the continent — because other similar coastal-hinterland areas now lie drowned beneath the sea."