Aerial drones equipped with lasers have revealed the secrets of the Battle of the Bulge, the largest and bloodiest battle fought by the U.S. in World War II.

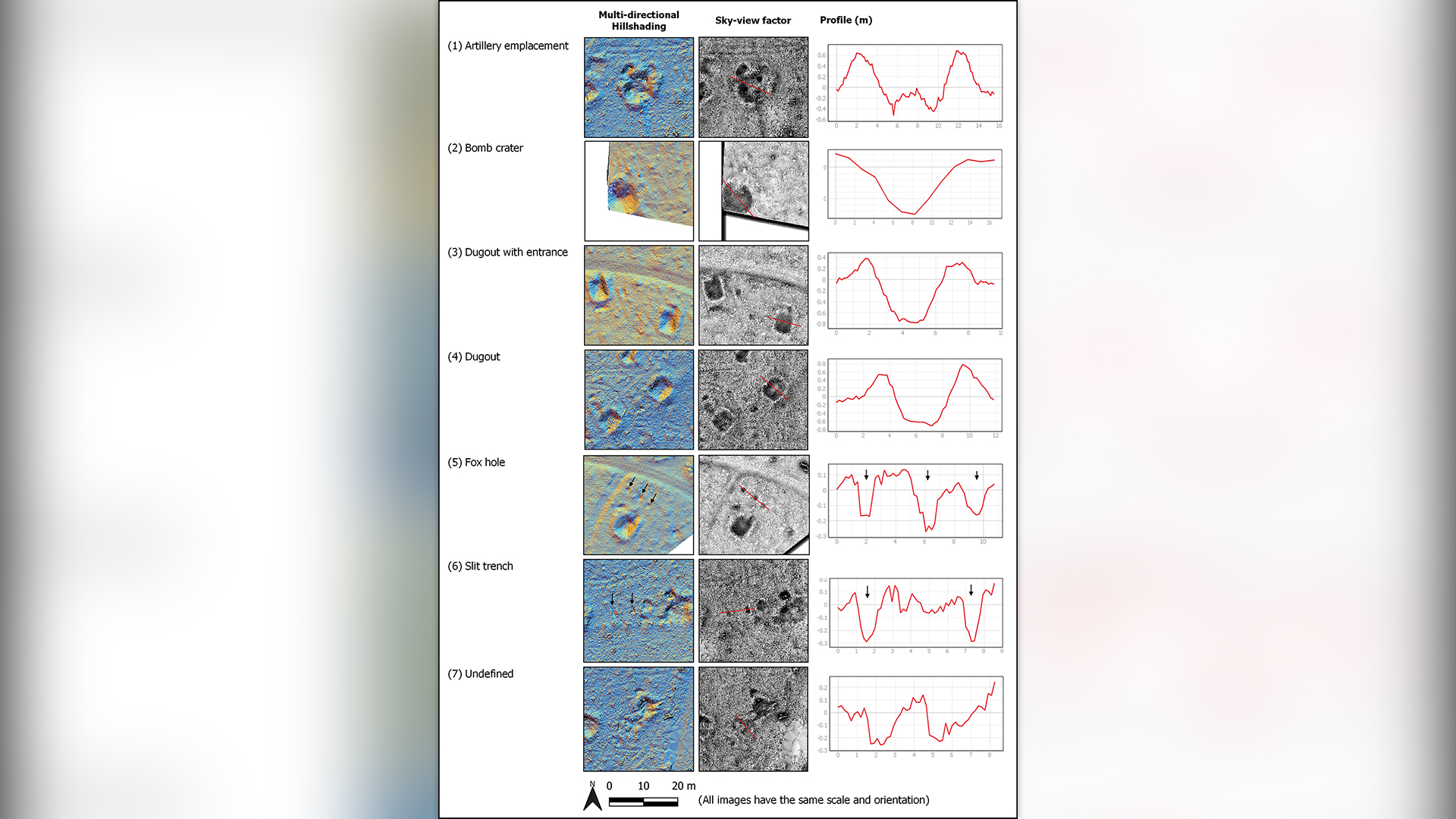

The drones revealed 941 traces of the battle, including dugouts and bomb craters, according to a study published Tuesday (Aug. 15) in the journal Antiquity.

Officially known as the Ardennes Counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge took place between December 1944 and January 1945 in eastern Belgium and Luxembourg, according to the Imperial War Museum in London. Despite being such a huge WWII battle, dense forests in the region shrouded much of the archaeological evidence left behind.

"Although this is a 'high-profile' battlefield, studied intensively by military historians and the subject of significant attention in museums and the popular media, little has been published on its material remains," study lead author Birger Stichelbaut, an archaeologist at Ghent University in Belgium, said in a statement.

Related: World War II 'horror bunker' run by infamous Unit 731 discovered in China

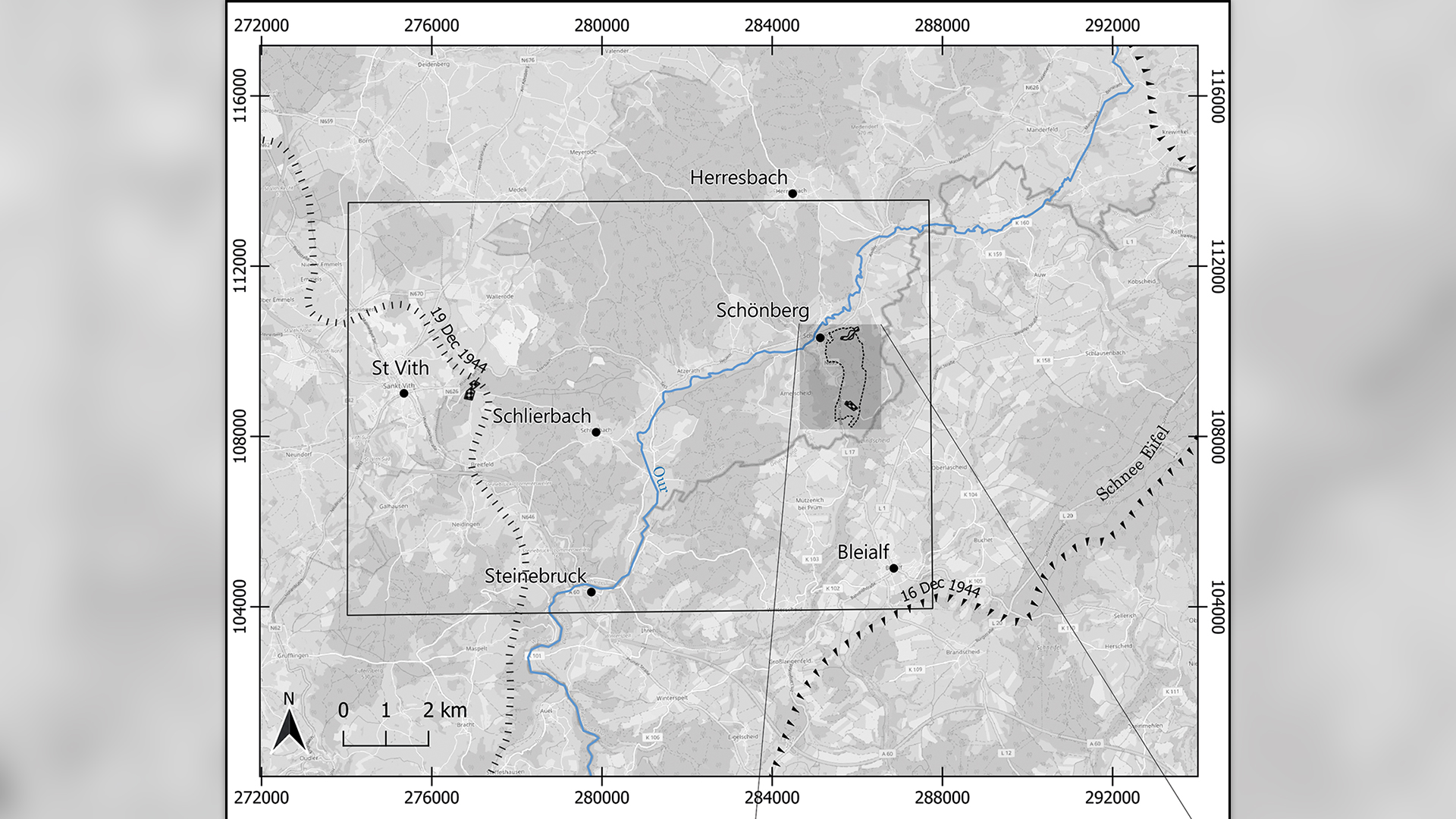

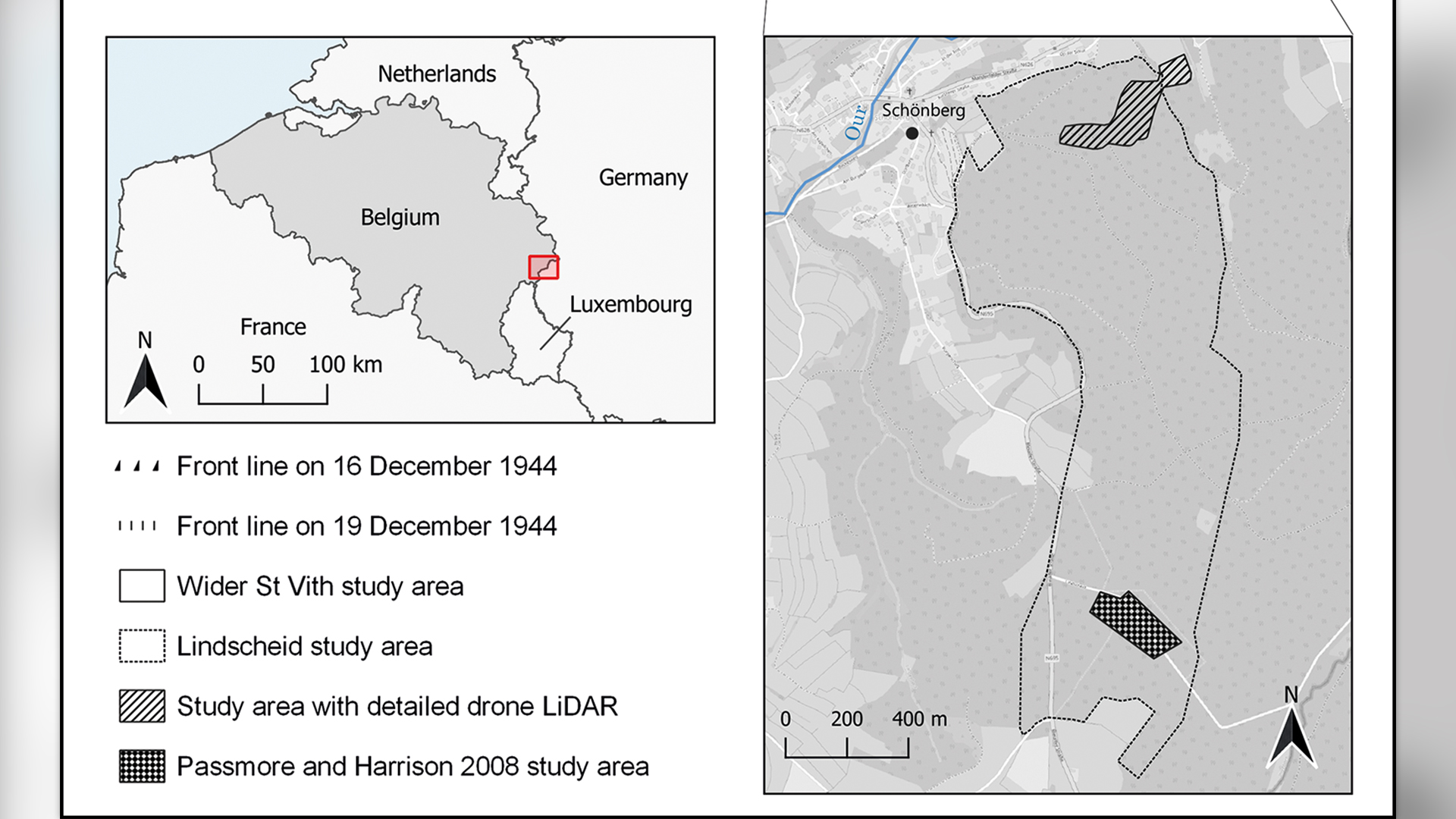

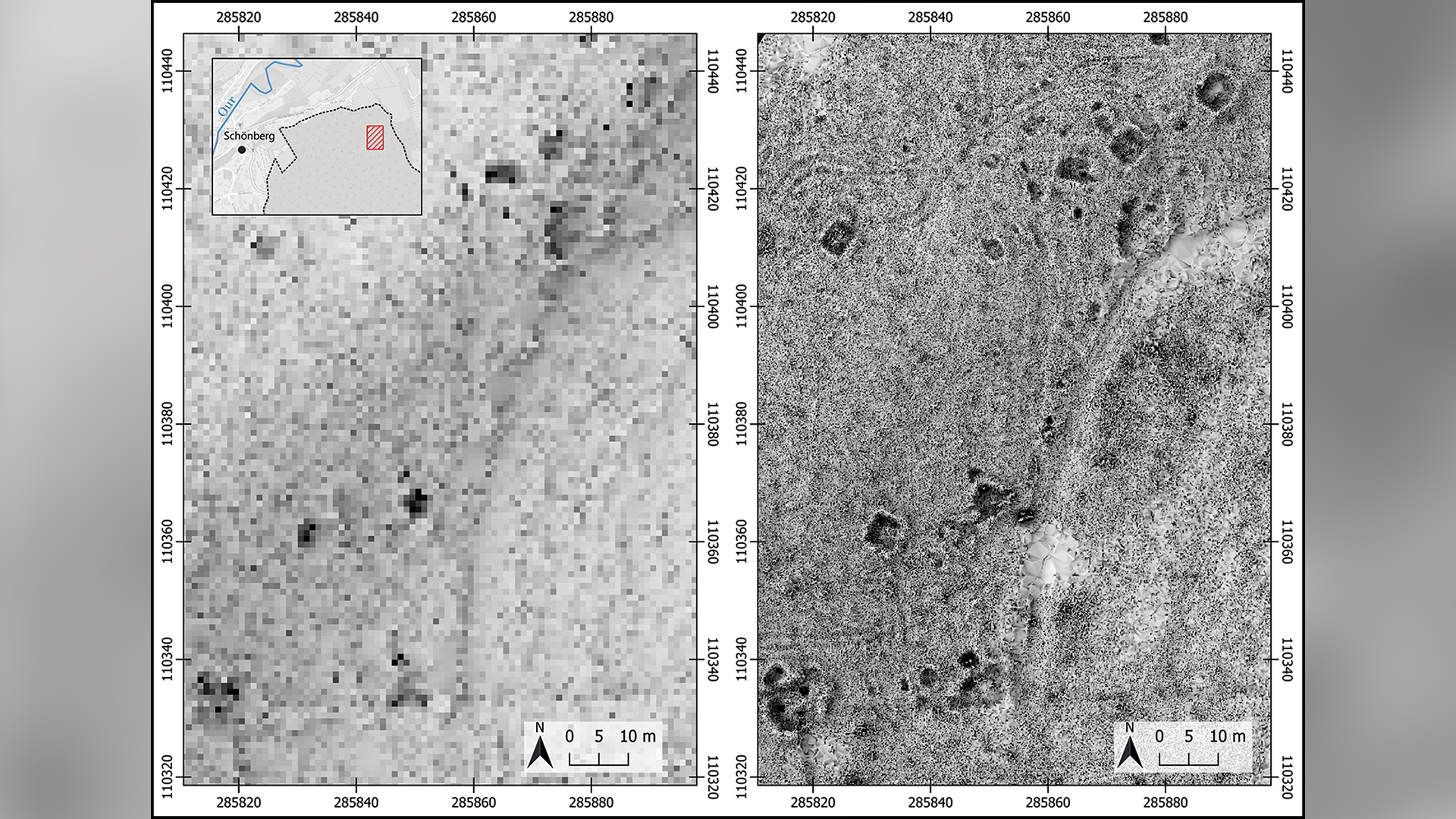

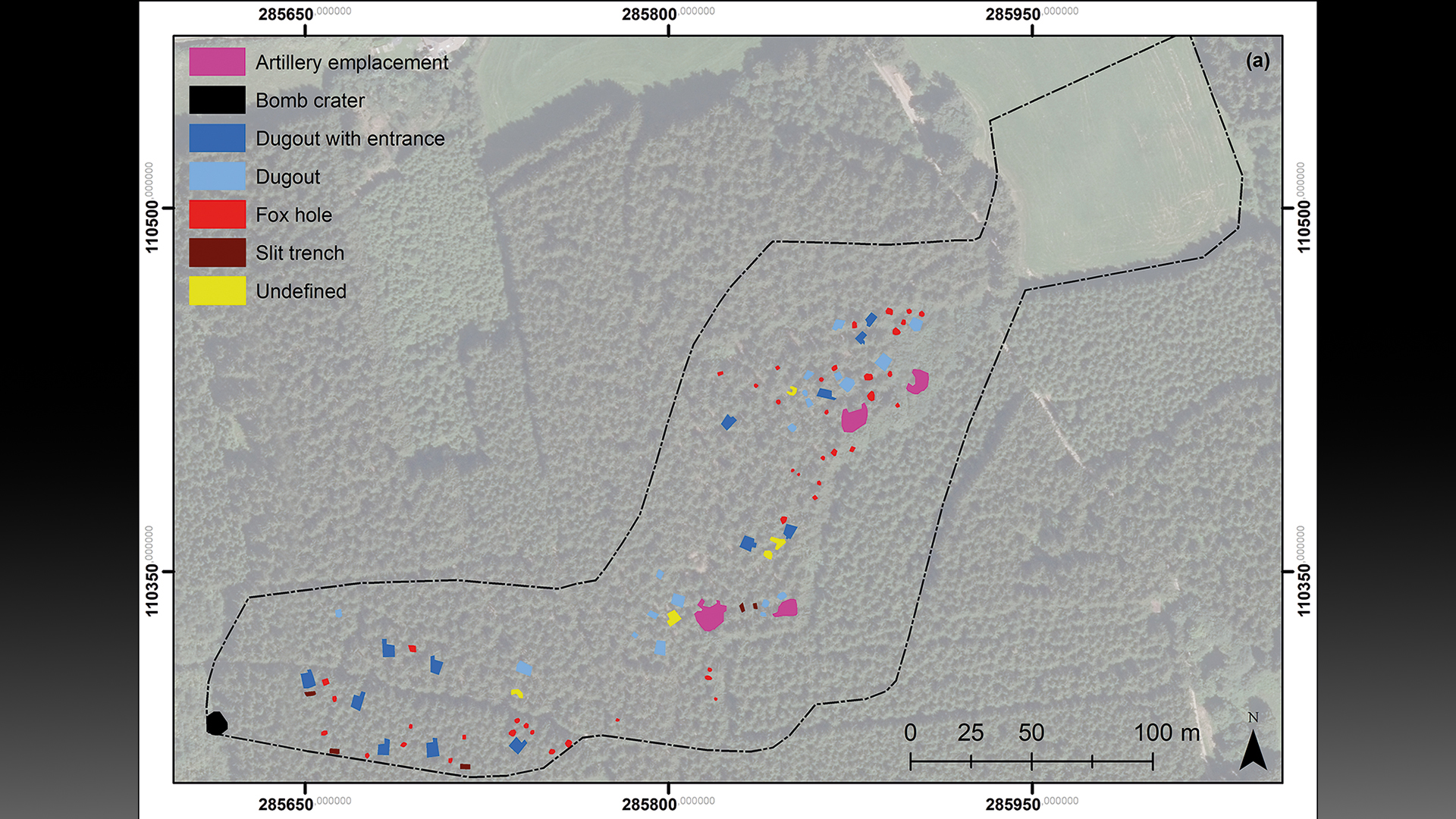

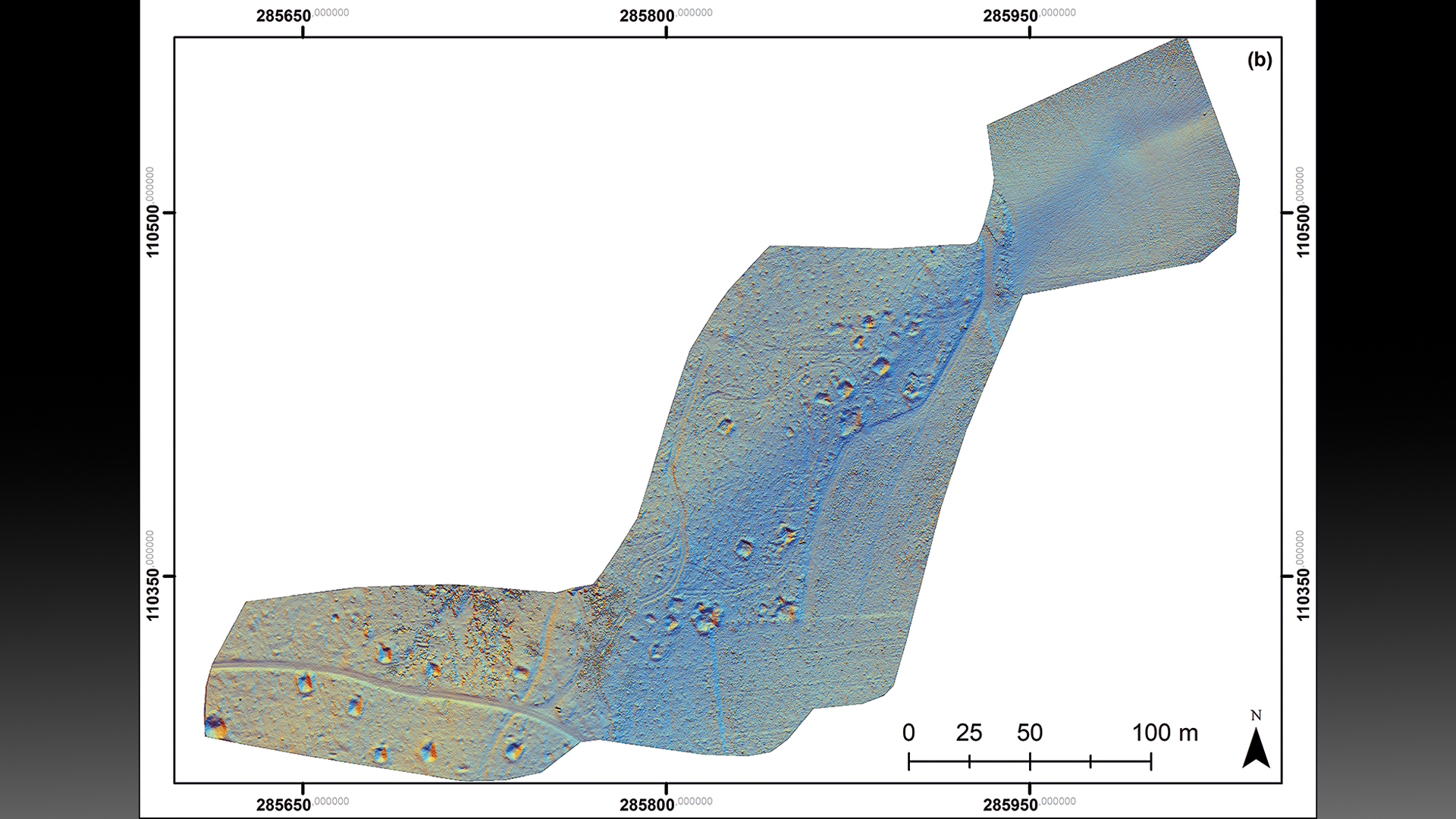

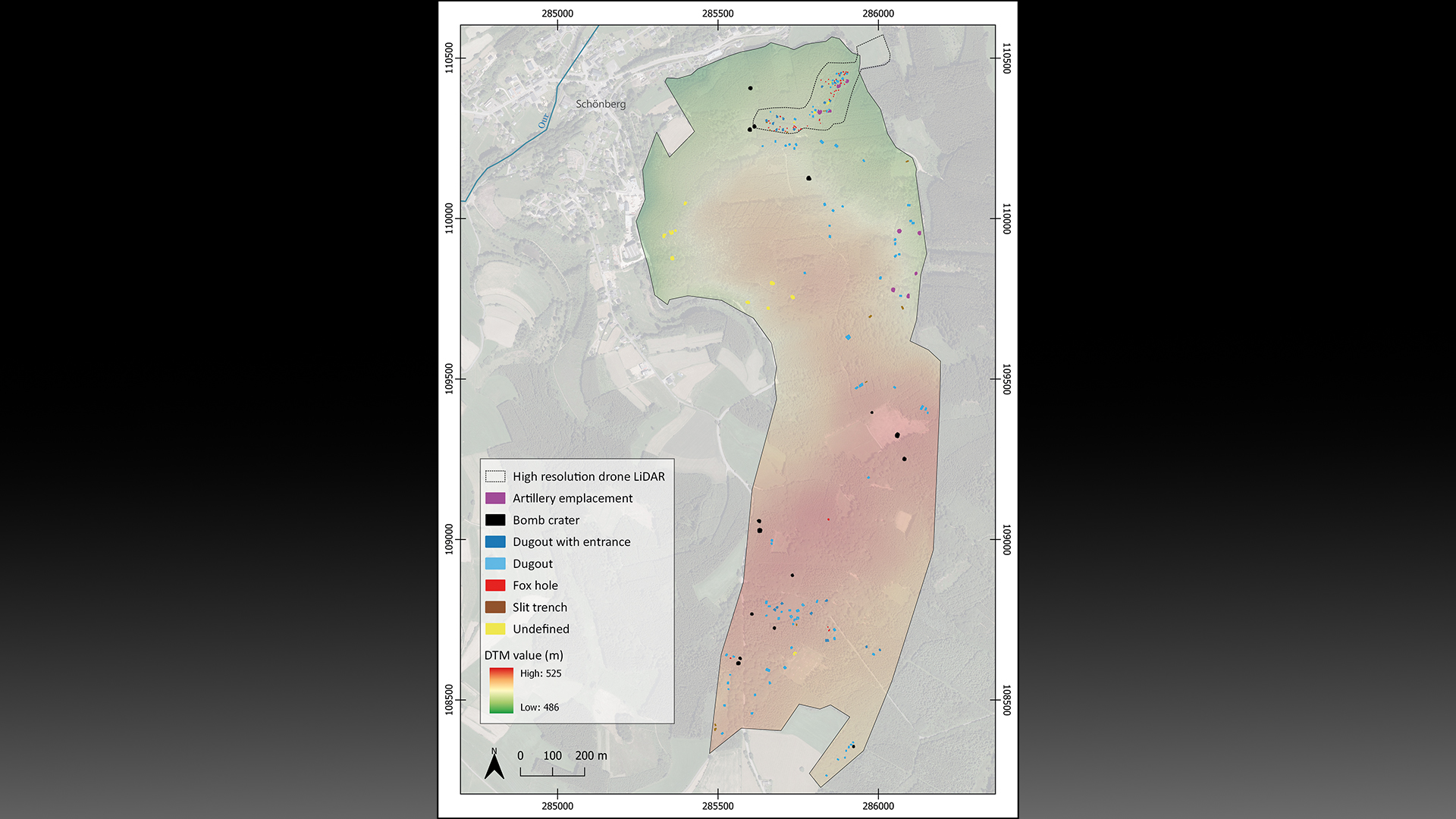

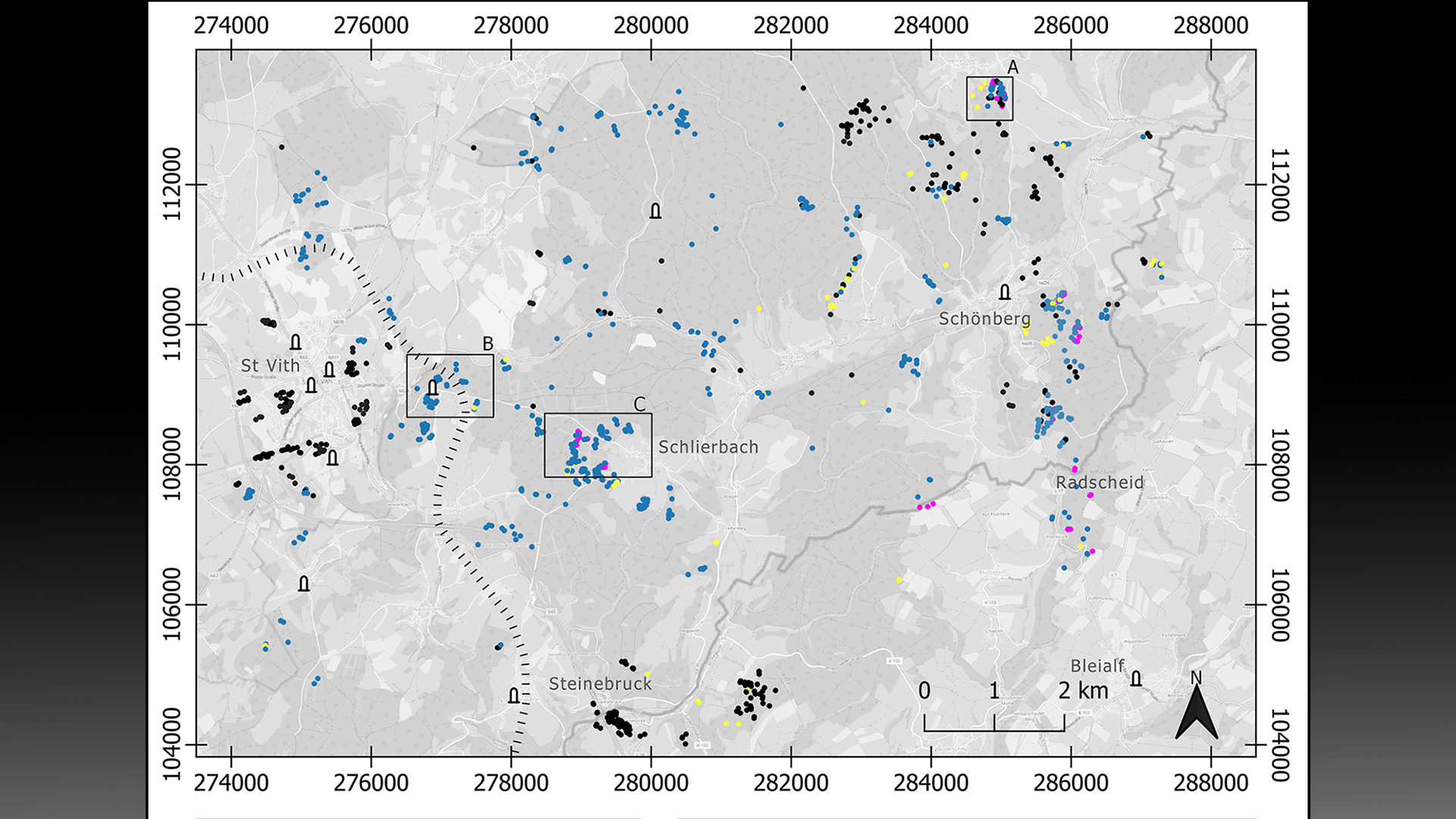

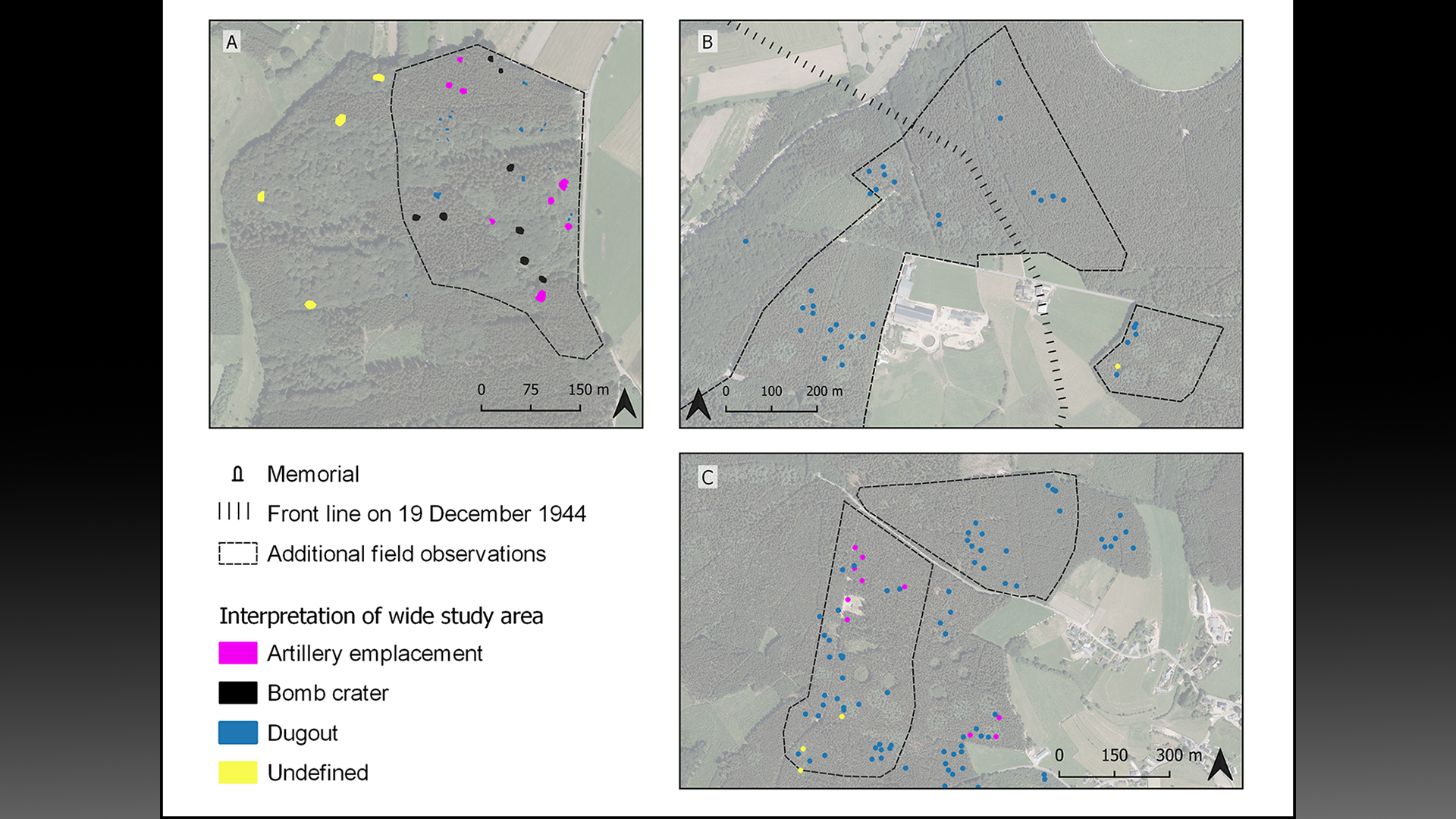

To uncover remnants from the battle, scientists outfitted drones with a remote sensing technology called lidar (light detection and ranging), which uses pulsed lasers to form digital maps of the landscape. They surveyed between the city of St. Vith and the village of Schönberg — an area that was once the central zone of the Battle of the Bulge — and discovered various traces of the war, including artillery platforms, trenches and foxholes (small forts to protect soldiers from enemy fire).

"This [lidar technique] allowed for traces of the battle to be observed on a scale not known until now," Stichelbaut said.

After discovering these features on the virtual map, researchers visited the sites, which helped them identify three distinct phases of the Battle of the Bulge. During the first phase, before the offensive, the Allies maintained a steady front line using U.S. field artillery battalions positioned a few miles west of the area. The researchers surveying this area found artillery fuses, artillery platforms and field fortifications that they believe can likely be attributed to this pre-offensive phase.

During the second phase, at the start of the German offensive, more than 200,000 German troops and nearly 1,000 tanks launched an attack on Allied soldiers. This mayhem left behind field fortifications and German objects at American artillery banks, which likely means that German forces used abandoned American fortifications during the battle, the study's authors wrote.

The final phase was the turning point of this battle, marked by "numerous extant bomb craters," which "indicate that the Allied air forces were able to establish tactical dominance once the weather improved," they wrote. However, the researchers added that some of these craters may have been from earlier points in the battle.

"This paper highlights the wide range of new technology, including LiDAR and drones, that is now being employed by [conflict] archaeologists," James Symonds, a professor of historical archaeology at the University of Amsterdam who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. He added that this research shows how contemporary archaeology can shed new light on "well-known historical events from the recent past."

Moving forward, this technique could be applied to other forested areas of Europe, thereby growing our understanding of different battlefields, the study's authors said. It could also help protect valuable heritage sites, according to Symonds.

"It is significant as it highlights the need to devise cultural heritage strategies to safeguard future heritage, while at the same time demonstrating the difficulties of recovering traces of mechanised and highly mobile modern warfare," he said.