Dawn breaks and the vastness of Hexham Swamp awakes from its slumber.

The stillness gives way to a hidden universe of colour and movement that bursts forth across the 2000-hectare wetland.

Tens of thousands of commuters pass by this natural wonder as they travel between Maitland and Newcastle each day.

Yet few are familiar with the story of how this ecological gem was once sacrificed in the name of urban development before it was transformed back into a globally-recognised wetland rehabilitation project.

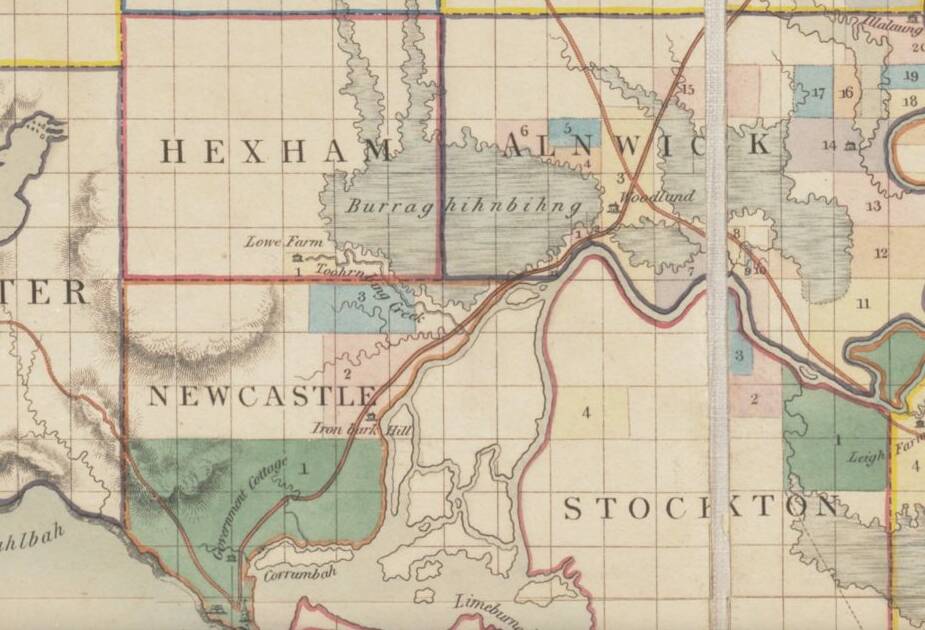

Burraghihnbihng

Before European settlement, the Indigenous inhabitants knew the area bounded by Shortland, Beresfield and the Hunter River as Burraghihnbihng, meaning "country of lots of freshwater eel".

Located near the foot of Keemba Keemba (Mt Sugarloaf), the estuarine wetland's tributaries would have stretched to Port Stephens and Lake Macquarie.

The vast array of Indigenous artefacts found around the swamp area suggest it was likely a shared space between the Awabakal and Worimi peoples.

"This is a place where people would have met up and shared stories," Awabakal cultural and heritage officer Matt Syron said as he surveyed the vast open space from a high point at Fletcher.

"We also know that it would have been a place for hunting and gathering."

A small tree-covered hill that juts out from the flat plain on the wetland's western fringe is known locally as Rocky Knob.

While little is known about the site, it is thought it may have been a ceremonial area.

"We don't know a lot about its cultural significance, or whether it was a sacred site," Mr Syron said.

"But the fact that it's a high point in such a flat area, makes it seem like it must have been a place of significance."

In her 1986 book, the Settlers of the Big Swamps, the late Hunter historian Dulcie Hartley provided a possible reconstruction of the landscape that the area's Indigenous communities would have lived in for thousands of years.

"Huge melaleucas surrounded the shallow margins interspersed with reeds; casuarinas abounded on the verges intermingled with dense undergrowth and many species of eucalypts. On the southern extremity, magnificent strands of Eucalyptus Maculata were found on the rises and rainforest species hugged the banks of the water courses meandering down to the big swamps," Hartley, whose great great grandfather was allotted a land grant at Hexham, wrote.

Colonial settlers, most likely passing through from Newcastle to the Hunter Valley, were first reported in the area in the early 1820s.

While there are no recorded interactions between Indigenous people and Europeans around Hexham, elsewhere in the Hunter the early 19th century was a period of intense conflict.

"You can imagine the turmoil it would have caused as the settlers pushed into this area from Newcastle and down from Port Macquarie," Mr Syron said.

"The families that would have been living in an established area for thousands of years were suddenly getting forced out. It would have been chaos because they would have been trying to stay away from the Europeans but also not cause trouble with other mobs that they would have been colliding with."

Bunyips stalked early settlers

As Newcastle and Lake Macquarie grew throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Hexham Swamp remained largely unchanged.

The first land grant in the Hexham area occurred in 1828 when Edward Sparke Senior received 809 hectares. A year later Alexander W Scott was granted 1000 hectares, which was increased to 1130 hectares.

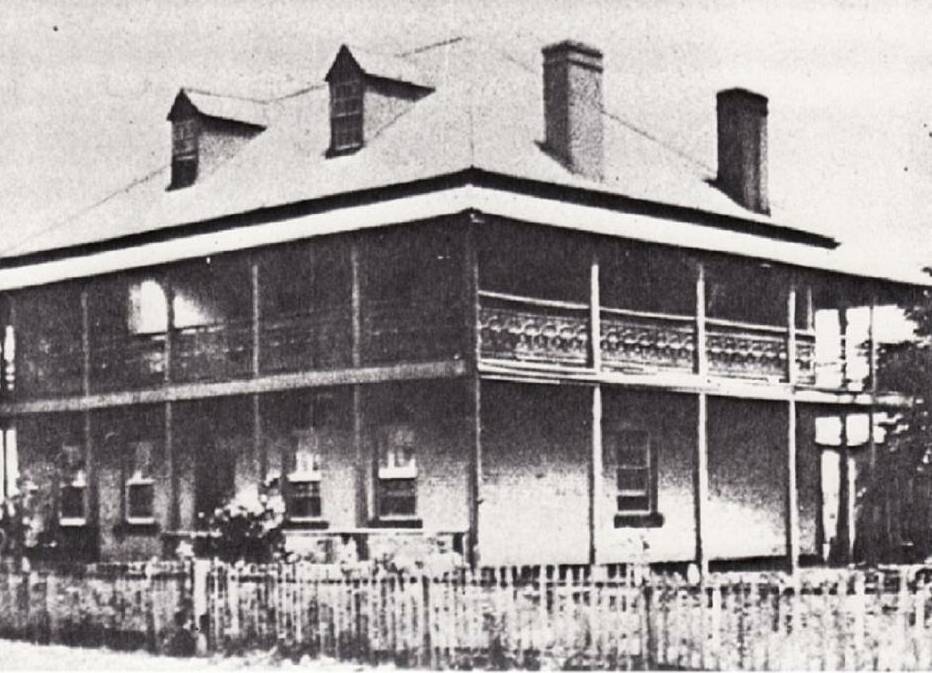

Another prominent identity was John Hannell (1815-1891), the brother of Newcastle's first mayor James Hannell.

In addition to being the proprietor of the Wheat Sheaf Inn, one of the two hotels that once stood in Hexham, John Hannell also operated a nearby racecourse.

A stone vault that once held the remains of Hannell and his wife Mary Ann still stands on the Hunter River bank near the confluence of Purgatory Creek.

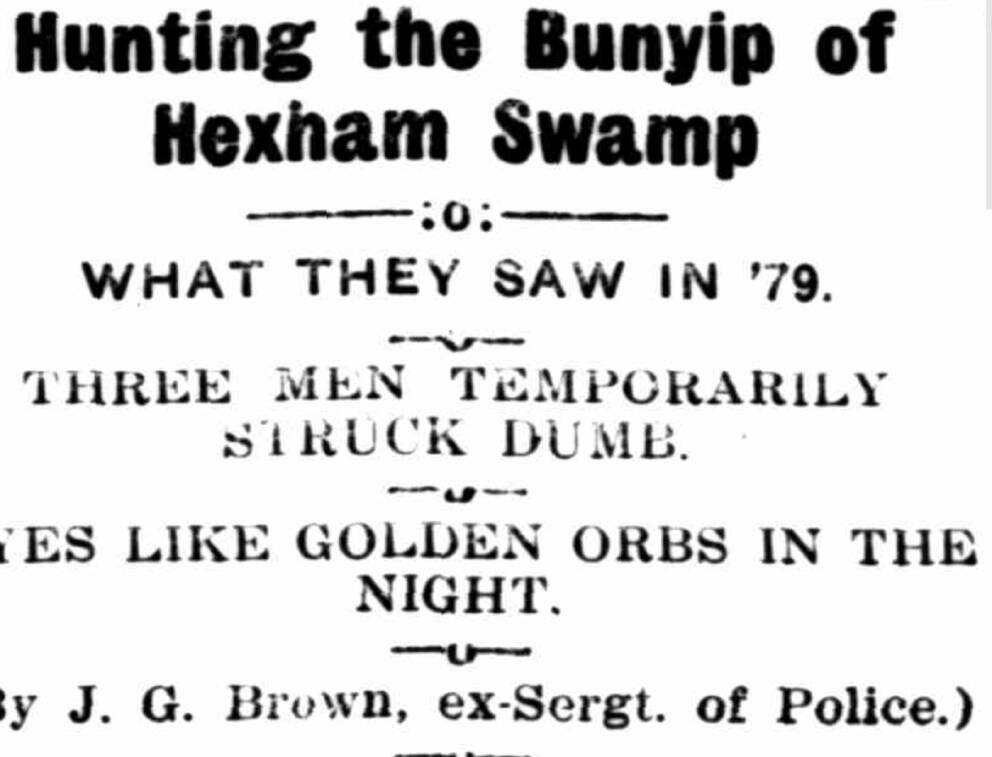

Many of those early settlers believed the area was haunted following reports of guttural growls emanating from deep within the swamp.

It was widely believed these sounds were made by a bunyip that inhabited the area.

Former police sergeant J.G Brown recalled an incident in 1878 when three men believed they had encountered the creature as they were leaving the swamp following an evening's duck hunting.

"While saying unkindly things about the absence of the ducks, without warning, a tremendous roar, like that of a lion, but very much more powerful, coming from one throat, rang out in the still night," Mr Brown told The Don Dorrigo Gazette and Guy Fawkes Advocate in 1925.

They looked in the direction from where the sound came, and they subsequently stated that all they saw were two golden orbs, about the size of soup plates, at a distance of 20 yards.

"The loudness of that roar and the sight of those golden orbs entirely took their speech and the power of their arms away. They looked at each other, blankly and stupidly, quite unable to utter a word or to lift their guns to their shoulders and fire."

A year earlier Mr W. Turton, who was born at Hexham's Wheatsheaf Inn in 1856, told the Newcastle Sun that stories about the bunyip, which the Irish settlers referred to as a banshea, were rampant during his childhood.

That was until he and his grandfather John Hannell were able to provide a factual explanation for the mysterious noise.

"About 1864 Mr Hannell [who was a noted duck-shooter] and others started investigating, and as he and myself were almost continuously on the swamps, it was not long before we located the 'bunyip', which proved to be not a mosquito but a bird named the bittern," Mr Turton wrote.

"After some years absence from the district I returned to Hexham in 1918 for a period of two years, and while there the bunyip and banshea were still to be heard."

Do you think that Hexham swamp is fully appreciated by the Hunter community? Email news@newcastleherald.com.au or join the discussion below.