In the latest reported incident of atrocities towards people from the Bahujan community, a group of Dalit and OBC students were forced to clean the septic tank at the Morarji Desai residential school in Kolar district. The principal and a few staff were arrested following the incident.

Caste and all the problems associated with it continue to be an ugly reality in Indian society even today, eight decades after Dr. B.R. Ambedkar wrote about the annihilation of caste. A structural problem, it often goes unnoticed or gets brushed aside, thanks to the extent of its normalisation and a certain gaze through which people have been conditioned to view.

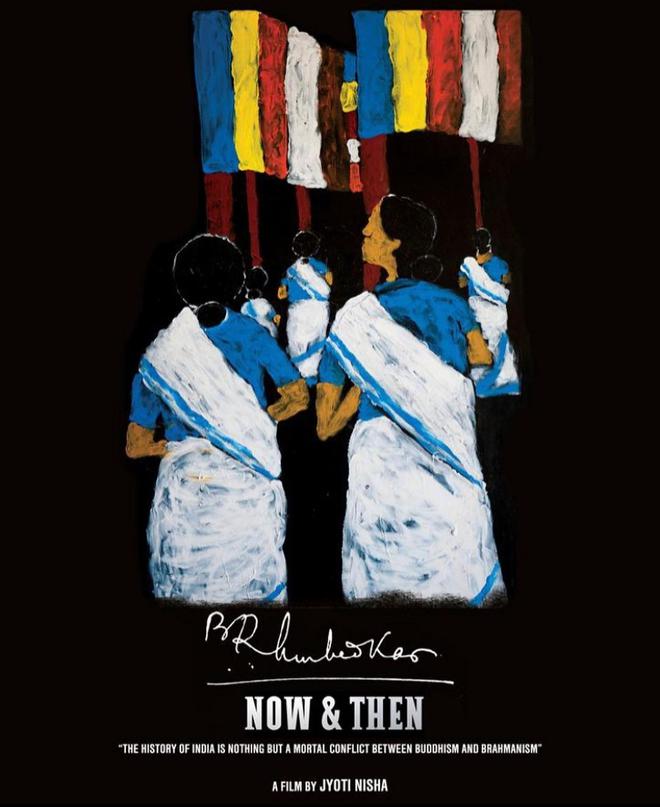

In her debut documentary film Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: Now and Then Jyoti Nisha, a Mumbai-based film maker, tries to break this gaze and dons the role of the protagonist to offer the audience a new way of seeing things.

Ms. Nisha’s movie progresses through multiple events and stories - from Poona pact to Una Dalit flogging incident to the mythological story of Ekalavya to Rohit Vemula’s death - in a non-linear fashion, while also talking to prominent voices from the Bahujan community including film-maker Pa Ranjit (co-producer of the movie), Raya Sarkar who compiled the LoSHA list of sexual harassers in academia, politicians like Jignesh Mevani, Bhim Army president Chandra Shekhar Azad, and so on.

To all of their voices and experiences, the protagonist apposes her personal experiences and (un)learnings and weaves together a story of resistance from an angle unfamiliar to many. She slowly unfurls before the audience how caste rears its ugly head not just during extreme acts of violences that get reported, but in our everyday lives, all around us.

The feature-length documentary discusses multiple issues including the entrenched casteism in the Indian society, Brahmanical patriarchy, appropriation of Ambedkar, influence of popular culture, dominant narratives and importance of Ambedkarite values. The idea is to educate, says Nisha.

The film, which premiered at Dharamshala International Film Festival on November 7, was screened in different parts of Bengaluru in December followed by discussion with the maker.

In a conversation with The Hindu, Jyoti Nisha talks about why she made the movie, the new lens it tries to offer the viewer, and the need to educate people.

Excerpts from the Interview:

Your documentary Dr. B.R. Ambedkar: Now and Then takes a very comprehensive approach and touches upon a lot of topics and incidents including those from the past to more recent events. What was the motive behind covering all of them in one documentary?

My work is about identifying a certain kind of gaze. It’s a new knowledge. Of course, I draw on a lot of thinkers. But where did that gaze come from? Who was writing, who was painting and who had the power to tell the story? So, I look at it primarily from the perspective of gaze which is also a very male gaze.

Of course, I draw from thinkers like Bell Hooks. Women from our community, like Urmila Pawar, have always been talking about it. We’ve heard stories of Savitribai Phule.

Caste also comes into perspective because it’s a structural institution which oppresses you, and that is very conditioned in the psyche of people. It has come to a level that it has become a pedagogy. My work is also about addressing those structures and I wanted to talk to more people about it.

For example, you understand race. Similarly, caste also exists, but it’s very invisible. To realise it becomes a question of lived experience, representation and agency. It’s a question of having the capacity to tell our stories and educate. In popular culture, unconsciously we are imbibing whatever we are watching. Especially when you are at an impressionable age, you’re just having fun watching it. I have also done that. Popular culture creates that pedagogy which has conditioned a certain gaze. And then it takes away the opportunities of having serious intense real conversations. It’s really sad how it hijacks those moments, the labour and the agency.

So, when I understood the gravity of the situation and started thinking about my work, then it became about gaze, representation and agency, and having a completely different imagination of existence. I wanted to tell a story about assertion, a story about having this conversation.

These are the real things, I think, as an artist, that are very important to be raised. I wanted to say it because Bell Hooks says ‘popular culture is where the pedagogy is’ and it’s true. I don’t underestimate anybody. I just wanted to really speak with the structures.

I think that possibility really exists where you can seriously educate and behave like an intelligent and empathetic person. You should have the ability to give back. It’s very important and I wanted to address all of those things.

The movie nowhere tries to provoke the viewer although there was an option of doing it given the atrocities against the Bahujan community even today. Was that a deliberate approach?

Yes. When I understood the gravity of the situation, there was no space for personal anger. I think it’s a tragedy such things continue to happen and it’s completely structural. But I didn’t want to sensationalize it. The movie makes it evident that I’m not trying to offend you. I’m trying to tell you something, that these things exist, and this is how I feel about them. If it makes sense to you, it makes sense to you; If not, then I don’t know. People are different.

The intention is to educate, and I’ve made it with a lot of heart and honesty. I think in India, we are a caste-oriented society. Even if I don’t tell the story, I can see it. This movie is my way of addressing it.

Were there specific instances that made you feel that society is trying to assign a certain space for you or was it a gradual process of understanding?

I was raised as a child with a lot of self-respect. I did not understand the issues so well then but would still hear the stories. I have come across questions on how I dressed so well or spoke good English. I didn’t understand it then, but it felt weird.

I started understanding it really well only recently. When I went to the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, I really found a language for it and then it became really easy for me. It was when I understood it that it started feeling very personal.

Did the movie turn out as you had imagined it initially?

I did two edits. I’ve never made a film before, not even a short film. Of course, I’ve written about issues and taught in school. So, I understood a lot of these things. But the first cut, I felt, was not up to the mark. So, I took a break.

Then we did another edit. I’m also the producer of the film, so cost was a factor. It is so tough to independently do it. Friends, family and some money that I had made helped. But I had so much faith in the film always. There was never a thought of not doing it. It was always about how to do it.

So, I did another paper edit, sat down, brainstormed and contemplated. This time when I thought of it, it was about my gaze, who I am and the way I see things. I always wanted to speak to more and more people because it is about education. It is not an offensive film. It is really trying to have this conversation to make you understand the gravity of things, how long it’s been going on and how harsh it is.

In the documentary, you’re talking about how national movements have been predominantly viewed through a Gandhian gaze. How difficult is it to break away from dominant narratives in your opinion?

Not at all difficult actually. I have always heard stories which talked about ideologies, representation, the absence of representation and so on.

When I started shooting the film, I had some idea of how to do it from a perspective of assertion. I want to have a conversation, and you are free to question me. I will be very happy to answer.

Then it became about understanding social science and society. Reading amazing scholars like Noam Chomsky, Foucault, Bell Hooks, ‘Ideology and ideological state apparatuses’ by Louis Althusser and so on blew my mind. There’s so much literature out there including Maharashtrian literature and they really informed me. The theories made a lot of sense to the personal questions I had. When that happens, you start identifying with them.

I wanted to create some kind of a scientific structure with the film as well. I’m just asking people to have a scientific temperament when you are representing people from marginalised backgrounds or anybody from the margins for that matter. Another important question is who funds the discourse.

Have you started planning your next project?

I would love to do fiction and would really like to direct a feature film. I have written a couple of stories and am looking for producers. It really depends on the timing for something to click. But I’m a writer, I’m always writing.