But to advocates of the Chicago River and ecological preservationists, the Bally’s plan to replace the Chicago Tribune printing plant in River West can be a meaningful next step in the makeover of the riverfront.

The casino plan, still unfolding, will join an urban landscape in mid-transformation. Roughly since the beginning of this century, the banks of the Chicago River have been growing from bit player to star attraction, an ever more alluring aspect of a city where natural beauty can be scarce.

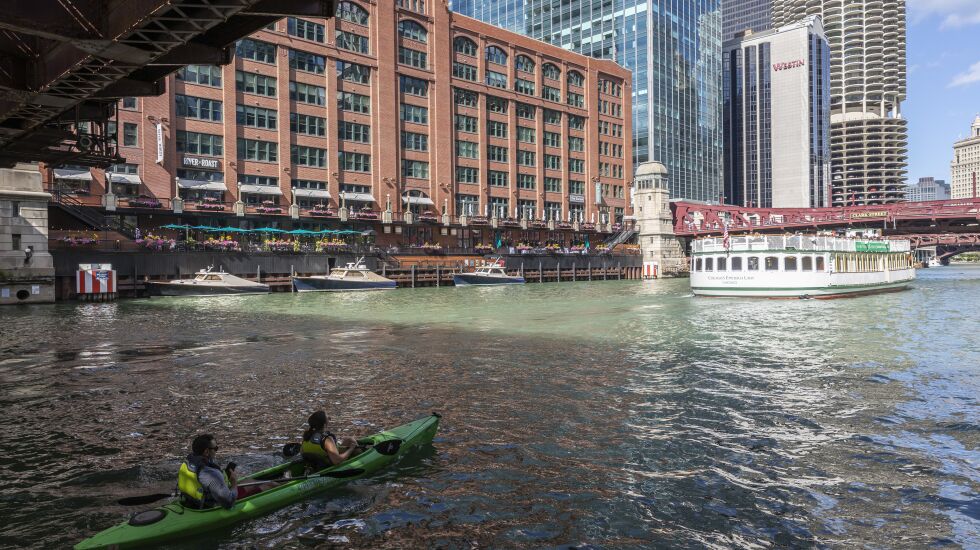

The Riverwalk is the shining example. The mostly unfenced waterside pathway has become an instant icon, a place to grab a drink or stroll for blocks without traffic. It’s a stark contrast to decades of riverfront development that put cold seawalls and sterile parking lots up against the waterway.

Things were so bad for so long that the city’s design guidelines for the river begin by noting its history of being “neglected and abused.”

“The Riverwalk has shown that people aren’t going to fall in and that we want to have that connection to the water,” said Jen Masengarb, executive director of the American Institute of Architects Chicago, noting that, in earlier phases of river development, protective fences were the norm.

Now, that centerpiece is mostly done, and the riverfront beautification is expanding up the North Branch and down the South Branch. The major, multifaceted real estate developments Lincoln Yards between Lincoln Park and Bucktown and the 78 south of Roosevelt Road enfold the river into their plans not only because the city requires it but because the people who would live and work in those places expect it.

That’s why the planned Bally’s Casino — which won the blessing of Mayor Lori Lightfoot and the Chicago City Council — feels so important. More than an opportunity for tourists to pretend they’re James Bond at the craps table, the casino is a chance to do riverfront development the right way, advocates say, with green space and easy public access by canoe, Divvy or shoe leather and a land-use plan that embraces the waterway rather than tolerates it.

Many of the details are being sorted out. But advocates say enough safeguards are in place to ensure that what happens at the casino site will improve the river, too.

“I’m stating the obvious here, but the transformation of that stretch of the river between Function A, what it was, and Function B, what it will be, is going to be one of the most dramatic switches that we’ve seen in the river,” Masengarb said.

For now, the big printing plant known as Freedom Center shrugs off the river with its stark brick wall. Along with the property’s massive private parking lot, it holds the “saddest park ever,” according to what Masengarb said she’s heard Chicago Architecture Center river tour docents call it: “There’s, like, one picnic table.”

So what’s going in its place will be, almost by default, a big improvement. And it will be significant beyond its site as a key part of the connective tissue linking the improved river downtown to what it will be elsewhere.

“The casino district now creates a destination,” said Maurice Cox, Lightfoot’s planning and development commissioner. “So, for me, I feel like that’s the next thing: Let’s establish a green agenda and character of the casino district. And that will then inform the way the rest of the river should develop.”

River access a key selling point

The Chicago River Design Guidelines is the city’s bible for riverfront development, a peek into dark history surrounded by rules for a brighter future.

“Renewed development and changes in technology have made it possible to reclaim the river,” it says, “as an aesthetic and recreational resource to improve the quality of life for all Chicagoans.”

In the renderings Bally’s has released, the riverside portions of the site are transformed into a kind of Riverwalk north, with dining options along the promenade. Wide steps descend from the casino’s clear-glass walls to the river edge, where water taxis can dock. Kayakers paddle out front. A terraced park toward the south of the property brings in fountains and green space, albeit in front of a fence at the waterside. A pedestrian bridge connects the casino site’s park area to an existing park across the water.

It all looks fairly friendly, a nice enough place to saunter even if you have no intention of tugging the handle of a slot machine. But pull back the focus, and you see how very long and low-slung the casino building appears to be, its mass overshadowing the pedestrian pathway and, to some degree, the river.

“There was a lot of outrage about a casino on the lakefront,” said Margaret Frisbie, executive director of the advocacy group Friends of the Chicago River. “And we said, ‘Well, the river is not any better of a place for the casino than the lake is. It’s a natural resource. It’s a human resource. It’s a community amenity.’

“However, if you look at that particular location now, it’s a seawall and a big building. So, if that turns into natural habitat and public access, I see that as a win in the long term, in the bigger picture.”

At this stage in the $1.7 billion Bally’s development — with an opening targeted for 2026 and including a 500-room hotel and 3,000-seat theater on the 30-acre site — a rendering can be a sort of Pinterest board of pretty possibilities designed to win over critics. In the interim few years, the city has said the casino can operate in the landmark Medinah Temple in the heart of River North, another fairly contentious choice.

But according to the river design guidelines the city adopted in 1999 and continually updated since, the property is required to have a 30-foot setback from the river. A community agreement between City Hall and Bally’s says the property must include riverwalk and parks and a publicly accessible pathway along its eastern edge, the border with the river.

The renderings “are very true to the general flavor that we want to introduce for the riverwalk environment,” said Joyen Vakil, senior vice president of design and development for Bally’s Corporation. “Having said that, they were conceptual…. It’s fair to say that, like with every rendering, they’re going to evolve.”

Vakil anticipates the essential plan for the site outlined in the renderings will remain, as will the general profile of the buildings. He sees the riverwalk as “a nice, walkable riverfront with food and beverage options.”

“At this time, we don’t have any plans for any kind of private boat docking,” he said, just a water taxi stop.

So there’ll be no high-rollers pulling up to the gambling den in their cigarette boats — or kayaks.

Now, as the casino proposal makes its way through various city and state approvals, Bally’s has started a kind of listening tour and sell job to community groups. Any pushback the casino can eliminate can help make the final zoning approval go more smoothly. And the path to least resistance involves, in part, riverfront design and access.

“We’ve been listening to what they have to say,” Vakil said. “And we are trying to incorporate as much of it as possible.”

The River North Residents Association, which represents more than 90 buildings across the river from the casino site, met with Bally’s representatives in July and has pivoted from its initial opposition to the site.

“We turned to trying to improve the project in a variety of ways that would lessen negative impacts” and ensure that provisions for riverfront access and green space will be upheld, said Brian Israel, association president.

One aspect of the plan includes an outdoor concert venue amid the park space at the south of the property. But the association told Bally’s the group isn’t keen on concert noise and traffic.

That venue plan remains under development, according to Vakil. “We are sensitive to what community groups have mentioned about nuisance” and are working to help make it “well-received among community members,” the Bally’s executive said.

The group also critiqued the planned pedestrian bridge connecting the bustling casino site to what’s now a quiet park.

“Based on community input, we decided that the bridge was not a good idea,” Vakil said. “So we’ve eliminated that from the project.”

Bally’s met with Frisbie’s group and has meetings scheduled with public-private advisory panels, the city’s River Ecology and Governance Task Force and its Committee on Design.

“We had a really good, open-ended conversation with them,” Frisbie said. “We talked about the design solutions we’d like to see: cutting down sea walls to minimum heights and slopes so that you can really get down to the water — and have a natural edge actually near the water as much as possible.”

Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development will have a big say in the final plan. As with the Lincoln Yards and 78 developments, the city is forming a casino community advisory council to keep people engaged ahead of and through the construction process and beyond.

“We’ve been really clear about the need both to program the [river] edge and to have a healthy setback,” Cox said, “but that we also wanted a kind of more naturalized edge.”

A more final plan is expected soon, said a planning department spokesperson, and its compliance with river design guidelines will be assessed. That plan, which will be part of Bally’s zoning application, will have to pass muster with the Chicago Plan Commission, the Chicago City Council zoning committee and the full council.

Even before that, the Bally’s plan needs license approval from the Illinois Gaming Board, an application it filed in August.

Slow to catch on to vision of ‘second lakefront’

The conversation happening now would have been unthinkable even a few decades ago. In early Chicago, the river was a place to dump human and industrial waste and a means of conveyance comparable to rail lines. The 1900 reversal of the river, sending the sewage toward St. Louis, was one step in its evolution.

Well into the 20th century, riverfront developers still seemed mostly uninterested in the river as a thing of potential beauty. Take the Freedom Center, opened in the early 1980s and still an example of an industrial-age waterfront.

“This is the second lakefront,” said Kathleen Dickhaut, the planning department’s deputy commissioner for systems and the river. “Chicago has done an excellent job of preserving the lakefront for public access. And the river was developed differently. That’s where all the industry went because it was the first highway.”

A turning point was the 1972 passage of the landmark federal Clean Water Act. Friends of the Chicago River was founded seven years later and has worked with the city to make the long-polluted river less grimey, even swimmable. The advocacy group has pushed the post-industrial vision for the Chicago River that calls for public use.

Ald. Brian Hopkins (2nd) was a critic of Bally’s plan for the Freedom Center site, preferring a plan proposed for the South Branch, amid the 78 development. Now, he is part of the chorus calling for key improvements in the winning plan.

“They put a lot more thought into how their casino at the 78 site would activate the riverfront,” Hopkins said. “Despite the fact that the Bally’s site is also on the river, they just gave it a cursory glance and really didn’t put a lot of emphasis on what they could do there.”

Cox disagrees. The Bally’s proposal was “the most inspired in many ways” of the contenders and meets city criteria to “actually address the river,” he said.

Vakil bristled at the suggestion the river was an afterthought in the plan. Bally’s executives and project designers spent a day in a bus, he said, touring a handful of Chicago riverfront sites for inspiration.

The river “has certainly not been an afterthought,” he said. “It is an integral part of the design of the project.”

That sort of thinking is still evolving in Chicago. Even the first phase of the downtown Riverwalk, the portion that runs from Michigan Avenue east toward the lake, was “pretty far above the water,” said Frisbie, a distance that was removed for the second and third phases. Now, people stroll past floating gardens, have a drink on riverfront steps near docking boats and sit in Adirondack chairs for concerts.

South of the Loop, the recent Southbank development goes even further. Yes, there is a riverwalk out front of its two apartment towers, part of a South Side path planned to extend to Chinatown. But the river edge, with native plantings that support biodiversity, is what really caught Frisbie’s eye.

“This is the evolution,” she said. “And I think, going north, that the casino site can be that face of a green, healthy, natural river in an urban area” — a lovely, lively riverfront first and then, yes, slot machines.”