PHILADELPHIA — Doug Collins finally got his golden moment 37 years after his heart was broken in Munich.

After Mike Krzyzewski guided Team USA to the gold medal in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he rewarded his staff by giving them replica gold medals. One went to Doug’s son, Chris — then Coach K’s assistant at Duke but for the last 10 years the head coach at Northwestern.

A year later, Collins was being celebrated in Springfield, Massachusetts, as a Hall of Fame recipient of the Curt Gowdy Award for broadcasting. The irony certainly wasn’t lost on Collins that if not for chronic foot problems during a four-time All-Star career, he might’ve gone in as a player. He also had 442 regular-season wins as a coach, including 137 with the Bulls.

Then this already triumphant occasion suddenly became even more memorable.

“Chris stood up and was trying to fight back tears,” Collins, 71, recently recalled. “He said, ‘Dad. I have something for you. It’s 37 years too late, but you’ve got your gold medal.’ And he walked over and put it around my neck.”

Chris Collins wasn’t even born on Sept. 9, 1972, when his father and the rest of Team USA were denied the gold in what went down as a 51-50 loss to the Soviet Union. He has only watched video and heard stories about how the Soviets were given three chances to win after his dad swished two free throws with three seconds left to put the Americans ahead for the first time all night.

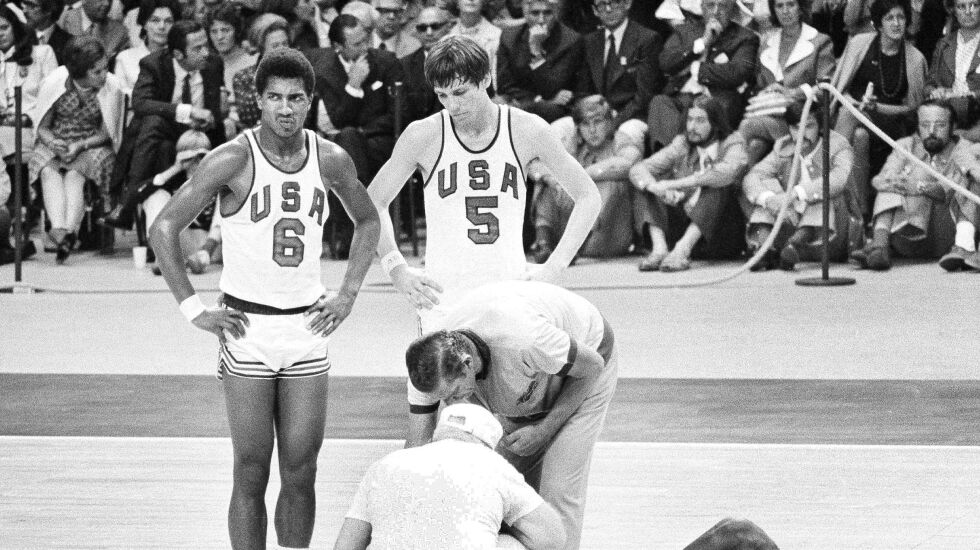

That came after Collins swiped a pass and was driving hard to the basket before being submarined so hard by a Soviet defender that he wound up on the stanchion behind the basket. But Collins and everyone else remain so convinced they were wronged in those final three seconds that the silver medals they refused to accept remain locked in a vault in Lausanne, Switzerland, 50 years later.

“We don’t want that silver medal; we didn’t win a silver medal,” Collins said defiantly. “We all feel we won the game and should receive gold.”

The Munich Games were rocked four days earlier when eight Palestinian Black September terrorists broke into the Olympic Village. They killed an Israeli coach and wrestler before holding nine Israelis hostage, demanding the release of 236 political prisoners.

Collins, then a 21-year-old Illinois State junior who had spurned a chance to turn pro early and landed a spot on the U.S. team, had never seen anything like it.

“We could see the terrorists had face masks and machine guns,” recalled Collins, who divides his time between Scottsdale, Arizona, and suburban Philadelphia. “When we came back from practice, there were armored tanks.

“We had no idea what was going on.”

He and the rest of the world would soon learn the nine hostages had been killed after a failed rescue attempt.

“Afterward, we’re wondering, ‘Are we going to continue the Games?’ ’’ Collins said. “My feeling was if we could honor those people killed by winning a gold medal, that would’ve been great. I just don’t think they would’ve wanted the Games stopped.”

That extra motivation seemed about to be rewarded when the Soviets inbounded the ball and were dribbling frantically up the court before the referee stopped play with one second left.

“I’m thinking they better not call a foul,” said Collins, who would coach Michael Jordan and the Bulls for three years before Phil Jackson took over and guided them to the top. “I never touched the guy.

“But they stopped the game. To this day, there was no reason for them to stop the game.”

Not only was the game stopped because the Soviets had illegally run onto the court to call a timeout, it was reset to three seconds at the insistence of William Jones. The British head of FIBA, Jones had made no secret that he was tired of America’s 63-0 Olympic basketball supremacy.

The timer was still winding the clock down when the referee, who spoke no English, inexplicably handed the Soviets the ball to start play. It was still showing 50 seconds when a short inbounds pass was followed by a desperation shot that went off the backboard as the horn sounded.

“It goes off the backboard, and the game is over!” Collins said. “I jump in the arms of Eddie Ratleff, my best friend, thinking, ‘My God, we just won the gold medal!’ All I could think was, ‘You’re going to step on that stage and get a gold medal! You’re from Benton, Illinois, a town of 7,000.’

“All this is going through your mind. And then, ‘No! No! No! They’re gonna let them do it again!’ ’’

Indeed, Jones and the officials decided that since the clock had never been properly reset, the play would be wiped out. That meant the Soviet Union would get another chance to win it — and it did.

Even on that play, when Ivan Edeshko threw a pass the length of the court to center Alexander Belov, who outfought defenders Jim Forbes and Kevin Joyce for the ball, then laid in the game-winner to set off a wild Soviet celebration, there was controversy.

First, the ref motioned 6-11 Tom McMillen, who was contesting the pass, to back off the line, giving Edeshko a clear look at Belov. Second, though the video is fuzzy, Edeshko appears to touch the end line before releasing the ball.

“It was one of those moments you wonder, ‘What just happened?’ ’’ Collins said. “It was snatched right out of our hands.”

The United States filed an official protest, which was rejected 3-2 because Cuba, Hungary and Poland were all Soviet-bloc countries. In frustration, the Americans voted unanimously not to attend the medal ceremony or accept the silver.

The bitterness stayed with Collins over the years, especially when he found himself broadcasting Olympics for NBC in Los Angeles (1984), Sydney (2000) and Athens (2004). That might have been why Krzyzewski and USA Basketball head Jerry Colangelo wanted him to address their troops in Beijing.

“We never got to hear the national anthem,’’ Collins recalled telling the team. “I told them I wanted those guys to stand on the podium and hear it as their last song.”

It worked.

“Before every game, LeBron [James] would point to me and say, ‘You’re a part of this’ ” Collins recalled. “When they won the gold, he jumped over the barricade and hugged me.”