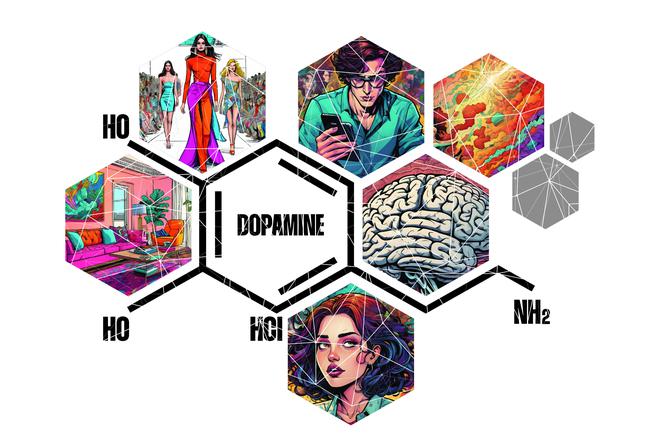

At 66, a ‘respectable’ age to slow down and retire, dopamine is having a moment. Discovered in 1957 by Swedish pharmacologist Arvid Carlsson, who won a Nobel Prize for the breakthrough, the neurotransmitter is thumping its squiggly little ‘tail’ and outrunning its fellow feel-good chemical cousins (serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins) in public consciousness. In fact, the reason we even know its physical structure is not through science, but because it’s a tattoo many non-scientists are getting and posting on social media (you can even buy it as a stick-on from Etsy.com).

Dopamine is in the news not because of any sudden breakthrough scientific research — researchers have been hard at work all along, slowly unravelling the mysteries of the neurochemical — but because of its ‘discovery’ by non-scientists. First, by the media over the past decade, fuelled by books on the subject, and more recently by social media, mostly over the years following the pandemic.

A little over a week ago, the Merriam-Webster dictionary updated its entry on the word, with examples just from 2023, from the world’s leading publications: The New York Times, Vogue, Elle, and more. Mostly though, it has been appropriated by the wellness industry, now pegged at $5.6 trillion, according to the non-profit Global Wellness Institute. Dopamine that is made in the brain, snuggles neatly into the space that sees an overlap of mental health, nutrition, and physical activity.

The chemical looking for reach

Dopamine, along with serotonin, oxytocin, and endorphins are together called the happiness hormones, and while scientists are studying their pathways and interactions, dopamine is of particular interest, says Chennai-based neuropsychiatrist Ennapadam S. Krishnamoorthy, because it plays a key role in the three Ms: “movement, memory, and motivation”.

Dopamine is a hormone that sends out that tingling feeling of anticipation, say like the night before a party at which you’ll be honoured with an award. Or the rush after a fantastic exam result. A substance released at the end of a nerve fibre, effecting the transfer of an impulse from one nerve to another, dopamine is, in essence, our morning’s get-up-and-go neurochemical. “We used to believe it’s all about pleasure and reward; this is an old story. Now we say that dopamine amps up desire. Dopamine is the brain signalling you to indulge in an activity; it is the anticipation of the activity from which you derive pleasure,” he says.

Like all good things, too much or too little is a problem. Too much has been found in the brains of those who live with Tourette syndrome; too little in those with Parkinson’s disease. But what’s really worrying researchers is the way it’s being increasingly pumped out in the brain through our daily behaviours.

“We used to believe dopamine is all about pleasure and reward; this is an old story. Now we say that dopamine amps up desire. Dopamine is the brain signalling you to indulge in an activity; it is the anticipation of the activity from which you derive pleasure”Dr. Ennapadam S. KrishnamoorthyNeuropsychiatrist

This anticipation of a good thing is at the root of additive behaviour. “We live in a dopamine amplified world,” says Dr. Krishnamoorthy, adding that while he wouldn’t go so far as to say our lives are driven by the neurochemical, it does feel that the way work and entertainment are structured today triggers its frequent release. For instance, online shopping in the world of 24-hour deliveries can heighten a dopamine release, triggering this repeated behaviour. It’s the same reason people have, for generations, been addicted to alcohol or drugs, but now, the easy access to technology has made screen addiction not just acceptable, but also desirable.

This makes us dopamine junkies waiting for our next ‘hit’. Phone addiction is real, with notifications, constant messaging, and endless scrolls, all feeding into the sense of micro-expectancy, which is key in dopamine release. And the ‘high’ of dopamine means the body wants that feeling again and again. Like a bottomless glass of cola that keeps getting refilled.

Anna Lembke in her book Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence, calls them digital drugs. “…We’ve transformed the world from a place of scarcity to a place of overwhelming abundance: drugs, food, news, gambling, shopping, gaming, texting, sexting, Facebooking, Instagramming, YouTubing, tweeting… the increased numbers, variety, and potency of highly rewarding stimuli today is staggering,” says the American psychiatrist.

Manoj Sharma, who runs NIMHANS’ SHUT (Service for Healthy Use of Technology) clinic in Bengaluru, published an article in the Asian Journal of Psychiatry this year, tweaking Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The theory that first came out in 1943, is based on a triangle, with physiological needs such as air, water, food, shelter, sleep, clothing, and reproduction forming its base — the most important for survival. Going up the triangle, there are safety needs (health, property), love and belonging (family, friendship), esteem (freedom, status), and self-actualisation. “We have brought technology under basic physiological needs because no one can survive without it today,” says Sharma.

All this is geeky brain-scientist stuff, though. Until fashion took it out of the textbook and gave it a nuance-flattening spin.

Fashion’s dalliance

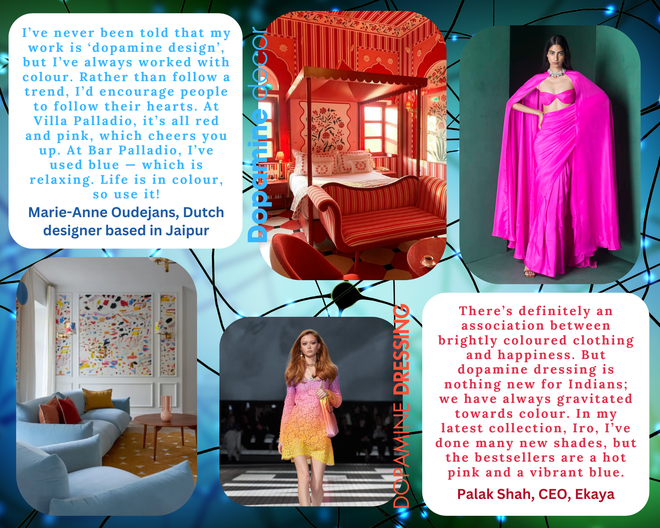

Post-pandemic, as people emerged from the collective grief of COVID-19, designers — tired from a year of disease and death, but also flush with the overdose of science news, through 2020 — showed spring-summer 2021 collections that were meant to cheer. Models wearing ‘mood-boosting’ riots of colour, pattern, and texture in ways that deviated from the controlled norm, strutted down the runway. Valentino did it and American rapper Lizzo wore it.

Soon, Dawnn Karen, dubbed by The New York Times as the “Dress Doctor”, coined the term ‘dopamine dressing’. The concept interpreted dopamine as a pleasure ‘particle’ (which it is not), but like all trends, spread quickly into home interiors with dopamine design and dopamine décor. Staid cream or white walls were thrown out the window and bold stripes, dots, and leafy patterns, sometimes all mixed and matched, began to be seen in homes — at least in photos from international magazines. Dopamine, the way designers saw it, brought in cheeriness.

In fact, dopamine isn’t the instant joy-giver it is made out to be. In The Molecule of More, co-authors psychiatrist Daniel Z. Lieberman and physicist-writer Michael E. Long, say the purpose of the neurochemical is “to maximize future rewards”.

Just as fashion got bored of the ‘trend’ — as fashion is wont to do — Gen Z, a generation that loves labelling everything, began to speak about dopamine dating, the buzz of looking forward to new experiences. This is closer in meaning to what dopamine really does. The forging of connections with the excitement that comes along, sees a dopamine secretion, heightened by dating apps, where people know very little about each other. As people enter long-term committed relationships, dopamine dwindles with time, though other happy hormones may kick in. The mid-life affair is a lot to do about the ‘high’ of dopamine.

Tech highs and lows

Investors latch on when they see an opportunity. This year, a few innovators are set to launch the AI-driven social fitness network dopamine.fit, with a seed funding of $1.1 million. They’re taking us back to the screen.

“Fads follow market economics,” explains Dr. Krishnamoorthy. Right now, the market is all around the screen, with careers such as user experience design and audience research coming into being this decade. In October this year, technology company Meta was sued by several states in the U.S. for deliberately designing features on Instagram and Facebook that are addictive.

The problem, as Sharma puts it, is heightened because technology is all around and inescapable. Unlike a person with an alcohol or drug addiction — who must abstain for life — someone living with tech dependence cannot say no to screens. Instead, they must learn to navigate the world differently.

One way of helping the brain cut back on this dopamine overdrive is what mental health professionals have called a digital fast for some years now, but what social media influencers call a dopamine detox or diet. “Dopamine detox” became a term that went through a “breakout” search on Google, meaning it saw a surge like never before, from being barely searched pre-pandemic.

Sharma uses digital fasting in his treatment of patients. He cites the example of a 15-year-old boy from an upper middle-class family in Bengaluru, who started gaming when he was nine. “He would spend up to 10 hours a day gaming. He had a history of ADHD, and an overinvolved, permissive mother, who had depression. The child was also witness to marital conflict,” he recalls. Many factors feed into addiction, just one of them being the excitement and euphoria of dopamine.

Immersion, involvement, interest are the words that Sharma uses for games and apps that are “difficult to decondition” people off. “This is because feedback is immediate in a game. In real life it may not be [no instant ‘likes’ or comments]. With family relationships suffering, real-life acknowledgement is also deteriorating. As the brain is stimulated with screens, it gets conditioned to this reinforcement of rewards. When you take it away, there are withdrawals,” says the psychologist, who sees 20 to 25 people in his clinic every week.

Pop science perceptions

This year, Poosh, American socialite Kourtney Kardashian’s lifestyle guide, posted to its 4.8 million users on Instagram, about dopamine, saying, “Chase real dopamine. Sun. Ice. Sauna. Weights. Runs. Walks... Do real work. You’ll never reach your potential, if fake dopamine is always within reach.” Hashtag pooshtheboundaries. By fake dopamine, perhaps Kardashian is referring to the chemical released when addictive behaviour is at play, or even medicines.

Many factors have brought us to this point of oversimplification of complex science, says professor Sujata Sriram, dean of School of Human Ecology, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. The industry around happiness itself, which includes self-help books, the rise of wellness that is often pushed through expensive products and services, over-zealous HR teams co-opted into plying employees with productivity matrices, and the positive psychology movement popularised by Harvard professor Tal Ben-Shahar. “Human beings like simple solutions,” she says, of pop science.

Prajwal B.S., 27, based out of Kolar, Karnataka, calls himself a dopamine induced copywriter on LinkedIn. It’s his job as a direct-response copywriter in a digital marketing agency to get people to buy products or services immediately, through the emails and other communications he writes. Prajwal grapples with the question: “Everyone makes a sale, but how are you triggering your customer at a subconscious level? And can you do this consistently?”

However, despite using it at work, he felt that for his personal well-being he had to have checks. He first heard about digital fasting from a friend, going on to learn more about it through American neurobiologist and ophthalmologist Andrew Huberman’s podcast episode in 2021, Controlling Your Dopamine For Motivation, Focus & Satisfaction. “We are constantly pulled to distraction, so I aggressively started deleting what was distracting me on my phone,” he says. The app he tackled first was Instagram, the most addictive for him. While he couldn’t uninstall it because he needs it for work, he cut his usage from 40 to 15 minutes a day. Prajwal blogged about it in his newsletter, BendTheReality. True to his generation, he believes he can write about things as he learns.

The present and future

Dopamine, like any other molecule, does not work in isolation in the body, and many parts of the brain’s workings are still a mystery. We do know that as people age, dopamine decreases, but the neurotransmitter is also related to genes — making dopaminergic impulses (rash, sometimes destructive decisions) hereditary, in much the same way that addictions like alcoholism are.

Last year, a team at the Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee developed a dopamine sensor to detect neurological diseases such as schizophrenia and Parkinson’s at an early stage. In the future, this could be a point-of-care device to calculate the amount of dopamine in samples. Professor Partha Roy, from the Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering, who was a part of the team that developed the device, says that dopamine’s role in regulating organs that govern the immune and digestive system is also being studied.

Today, in India, it can only be measured through functional imaging of the brain or a spinal tap, but food is a way to help keep levels balanced. Dopamine is made from an amino acid called tyrosine, a building block of protein. “There is a direct correlation of tyrosine and the formation of dopamine,” says Delhi-based dietician Manjari Chandra, who suggests that people make sure they get enough nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, hung curd, and good quality cheese for a vegetarian diet, and fatty fish and chicken, for those who eat it. “Without enough dopamine, even adrenaline [that can make you fight or flee in a tricky situation or get you to feel a rush when you play sport or exercise] may be affected, since this is a product of dopamine,” she says, adding that low dopamine levels could result in brain fog.

Roy adds that neural function is controlled by the microbiome, the community of organisms living in the gut. These flourish depending on the food we eat and the air we breathe, so the better the quality, the higher the number of ‘good’ bacteria. Despite its dopaminergic urges, if we feed it right, with healthy food, rest, and exercise, what the body bends towards is a state of balance.