Tonight (Aug. 19) skywatchers will be able to gaze upon a most "unconventional" full moon, because it will also be — a "Blue Moon."

But wait a minute, you might ask ... isn't a "Blue Moon" defined as the second full moon that occurs during a calendar month? August's full moon falls on Aug. 19 and it will be the only full moon of August 2024. So how can we call it a "Blue" moon?

Yet it indeed is a "Blue" moon, but only if we follow a now somewhat obscure rule. In fact, the current "two full moons in one month" rule has superseded the rule that would allow us to call this month's full moon "blue."

The Almanac rule

The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of the night sky. It's sturdily built, quick to set up and automatically locates night sky targets and provides crisp, clear views of them. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review

The confusion over exactly how to brand a particular full moon as "blue" can be traced back to "Sky & Telescope" magazine, which turned a literary lemon into lemonade by proclaiming that — however unintentional — it changed pop culture and the English language in unexpected ways.

In the July 1943 issue of "Sky & Telescope," in a question-and-answer column written by Lawrence J. Lafleur, there was a reference made to the term "Blue Moon." Mr. Lafleur cited the unusual term from a copy of the 1937 edition of the now-defunct Maine Farmers' Almanac (NOT to be confused with The Farmers' Almanac which is still published in Lewiston, Maine).

On the almanac page for August 1937, their calendrical meaning for the term "Blue Moon" was given.

That explanation said that occasionally "... one of the four seasons would contain four full moons instead of the usual three."

"There are seven Blue Moons in a Lunar Cycle of nineteen years," continued the Almanac, ending on the comment that, "In olden times the almanac makers had much difficulty calculating the occurrence of the Blue Moon and this uncertainty gave rise to the expression 'Once in a Blue Moon.'"

An unfortunate oversight

But while Mr. LaFleur quoted the Almanac's account, he made one very significant omission: He never specified any date for the Blue Moon.

And as it turned out, in 1937, it occurred on Aug. 21. That was the third full moon in the summer of 1937, a summer season that would see a total of four full moons. Names were assigned to each moon in a season: For example, the first moon of summer was called the early summer moon, the second was the midsummer moon, and the last was called the late summer moon. But when a particular season has four moons the third was apparently called a "Blue" Moon so that the fourth and final one can continue to be called the late moon.

So where did we get the "two full moons in a month rule" that is so popular today?

Pruett's Mistake

Once again, we must turn to the pages of "Sky & Telescope." This time, on page 3 of the March 1946 issue, James Hugh Pruett wrote an article, "Once in a Blue Moon," in which he made a reference to the term "Blue Moon" and referenced Mr. LaFleur's "Sky&Telescope" article from July 1943. But because Pruett had no specific dates to fall back on, his interpretation of the ruling given by the Maine Farmers' Almanac was highly subjective. Pruett ultimately came to this conclusion:

"Seven times in 19 years there were - and still are - 13 full moons in a year. This gives 11 months with one full moon each and one with two. This second in a month, so I interpret it, was called Blue Moon."

How unfortunate that Mr. Pruett did not have a copy of that 1937 almanac at hand, or else he would have almost certainly noticed that his "two full moons in a single month assumption" would have been completely wrong. For the Blue Moon date of August 21, 1937 — as is the case in August 2024 — was most definitely not the second full moon that month!

Going viral!

Mr. Pruett's 1946 explanation was, of course, the wrong interpretation and it might have been completely forgotten were it not for Deborah Byrd who used it on her popular National Public Radio program, StarDate on Jan. 31, 1980. We could almost say that in the aftermath of her radio show, the incorrect Blue Moon rule "went viral." Over the next decade, this new blue moon definition started appearing in such diverse places such as the Kids edition of the World Almanac, and the board game Trivial Pursuit.

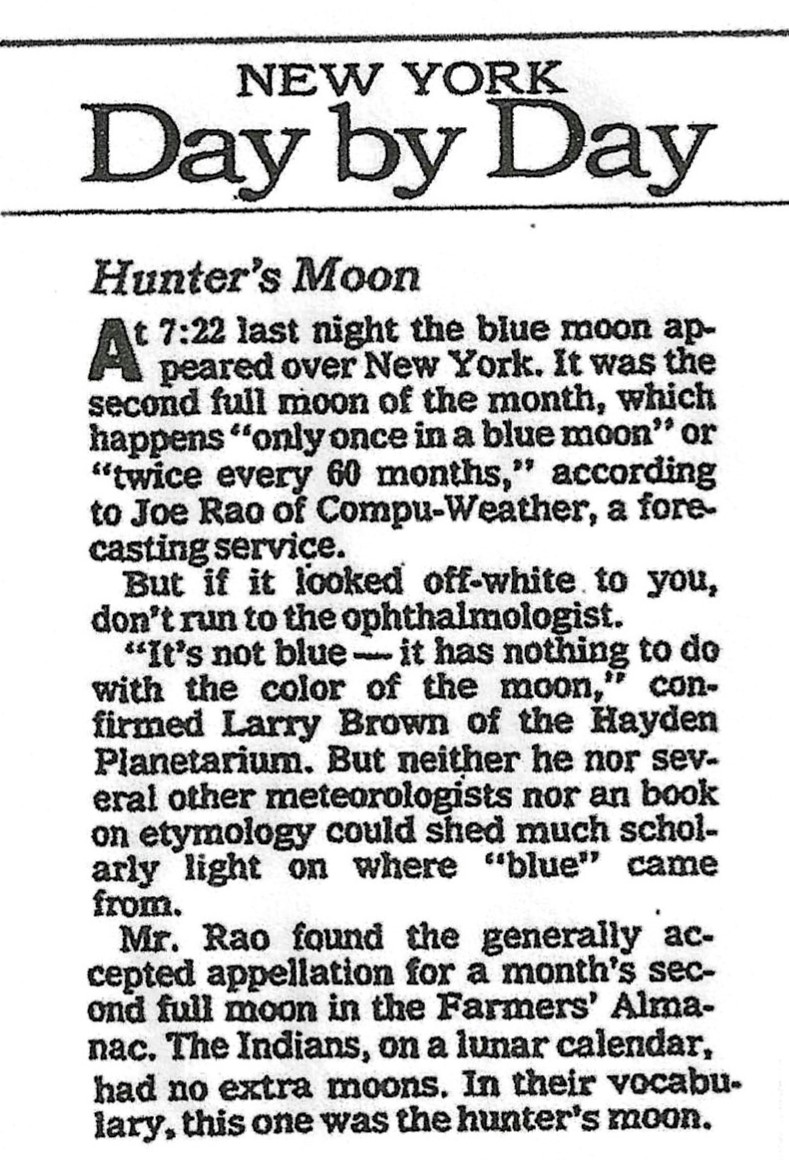

I must confess that I was even involved in helping to perpetuate the new Blue Moon phenomenon. More than 40 years ago, in the Dec. 1, 1982 edition of The New York Times, I made reference to it in the "New York Day by Day" column.

And shortly thereafter the new definition started receiving international press coverage.

Meanwhile, the original Maine Farmers' Almanac rule had been all but forgotten.

Playing by the (old) rules

Now, let's come back to this August's full moon.

Under the "old" Almanac rule, this would be a "Blue Moon."

For the summer season of 2024, there are four full moons:

June 21 Early Summer Moon

July 21 Midsummer Moon

Aug. 19 Blue Moon

Sep. 17 Late Summer Moon

This means that under the original Maine Almanac rule — the one promoted by Mr. Lafleur and later misinterpreted by Mr. Pruett — the third full moon of the 2024 summer season on Aug. 19 would be a Blue Moon.

Truly blue!

So, can the moon ever appear to actually turn blue?

Yes ... but only under certain atmospheric conditions. In the aftermath of the massive 1884 volcanic eruption of Krakatoa, a tremendous cloud of ash and dust was injected into the stratosphere (5 to 30 miles or 8 to 48 km) above Earth's surface). The tiny ash particles — about one micron in size — acted as a filter, scattering red light and turning both the moon and the sun a distinct bluish hue as seen from many locations in the Northern Hemisphere for many months after the explosion.

In addition, other volcanic eruptions have also been known to cause blue moons including the 1983 eruption of El Chichon volcano in Mexico and the eruption of the Philippines Mount Pinatubo in 1991.

And on Sept. 24, 1950, a 200-mile-wide (321 km) swath of smoke from a series of smoldering fires in the forests of Northern Alberta in Canada cast an awesome pall over the Great Lakes, parts of New York State and Southern New England. The smoke produced an unusual midday darkness and caused the disk of the sun to shine in eerie hues of pink, blue and even lavender!

Additional information

Explore Blue Moons in a nutshell with ESA's useful Blue Moon infographic. Check out this cool image of a Blue Moon captured by the European weather satellite MSG-3 just before the moon disappeared out of sight. Discover the difference between types of full moons with NASA.

Interestingly, this is the second consecutive August containing a Blue Moon. Last year, on Aug. 30, we had the second of two full moons in a calendar moon — maybe we should call it "Pruett's Blue Moon Rule." In addition, that full moon was also the closest and largest full moon of 2023; a "Super Blue Moon."

Take your pick!

So which definition of a Blue Moon do you prefer? If you go by Pruett's misinterpretation of the second full moon occurring within a calendar month, then that will happen in May 2026. The second full moon in that month — the "blue" moon — will come on May 31.

But if you prefer the "Maine Almanac Rule," where there are four full moons occurring during a single season (as will be the case this year), that will happen again in 2029. During that summer, the fourth full moon arrives a mere 39 minutes before the occurrence of the autumnal equinox (the official start of the fall season). So, the full moon of Aug. 23, 2029, can also be considered "blue."

And if you don't care for the blue moniker, you can always fall back on the traditional Native American branding of the August full moon: The Sturgeon Moon, named after North America's largest fish, the sturgeon.

Seems a bit fishy to me.

Want to get a closer look at the moon? Make sure to take a look at our guides to the best telescopes and best binoculars.

And if you want to photograph the moon, we have tips for how to photograph the moon as well as guides to the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.