For the next week or so, if you happen to be outside during the overnight hours and happen to catch a glimpse of a bright and colorful "shooting star" you might very well have just caught sight of a Taurid meteor. This annual meteor display shows up like clockwork every year between the middle of October and the middle of November, but Nov. 5 through Nov. 12 will be the best time to look for them when they reach a broad maximum.

Roughly 8 to 12 meteors per hour might be seen under dark skies during this period. Most meteor showers are at their best after midnight, because their radiants (apparent points of origin) are highest in the sky just before dawn. The Taurid meteor shower is an unusual case where the radiant is highest soon after midnight so the shower can be observed all night.

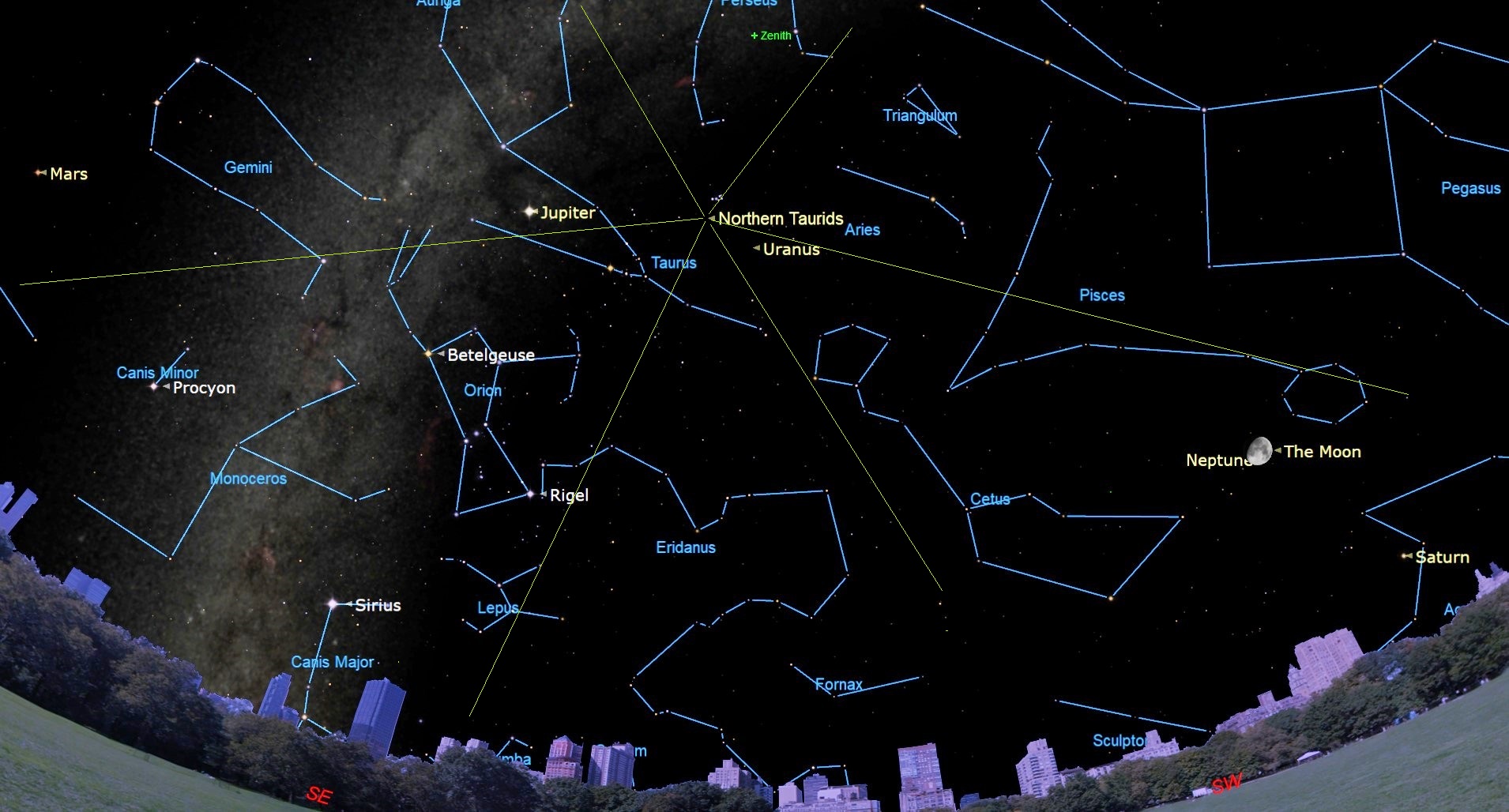

Their name comes from the way they seem to radiate from the constellation Taurus, the Bull, which sits low in the east a couple of hours after sundown and is almost directly overhead by around 1:30 a.m. The higher a shower's radiant is in the sky, the more meteors can be seen emanating from it. The moon was new on Nov. 1, and by Nov. 7, it will stay up until around 9:40 p.m. local time. By the morning of Nov. 12, it will be up until about 2:30 a.m., leaving the rest of the night dark for meteor viewing.

Bright, but sluggish streaks

Want to see the stars of the Taurid constellation up close? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

Meteors — popularly referred to as "shooting stars" — are generated when cosmic debris enters and burns up in Earth's atmosphere. In the case of the Taurids, they are attributed to debris left behind by periodic comet Encke, which last passed through the inner solar system in October 2023 and expected to return in February 2027.

The Taurids are the slowest of any major shower's meteors, encountering the Earth at only about 19 miles (30 km) per second. The Taurid stream is noted for its many brightly colored meteors. Although the dominant color is yellow, many orange, green, red, and blue meteors have been recorded. Occasionally this shower includes spectacular so-called "Halloween fireballs." These may grab attention anytime for several weeks, not just on Halloween.

This shower's debris stream contains noticeably larger fragments than those shed by other comets, which is why this rather elderly meteor stream occasionally delivers a few unusually bright meteors known as "fireballs."

Two showers for the price of one

The Taurids are actually divided into the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids. This is an example of what happens to a meteor stream when it grows old. The southern component of the Taurid shower peaks in early November, the northern component in mid-November. They overlap, and each runs for many weeks. During this time their large, diffuse radiants migrate all the way from southeastern Pisces across southern Aries to well east of the Pleiades. The radiant regions climb the eastern sky during the evening so no post-midnight vigils are required. But if it weren't for the possibility of fireballs, this would be considered a modest shower of minor interest.

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown, in the 2024 edition of the Observer's Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the Southern Taurids reach maximum on Nov. 5 and the Northern Taurids reach their peak a week later on Nov. 12. The two radiants lie just south of the Pleiades.

So, during the next week, if you see a bright, yellowish meteor sliding rather lazily away from that famous little smudge of stars, you can feel sure it is a Taurid; a piece of Encke's comet.

Want to try your hand at photographing the Taurid meteor shower? Check out our guide on how to photograph meteors and meteor showers. And don't miss our guide to the night sky for tonight, updated daily with what you need to know for watching the skies.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.