Linkin Park had long established themselves as the most successful rock band of the 21st century by 2014, but their journey had taken some unexpected twists and turns to get there – ones that longtime fans weren’t always happy with. But with that year’s The Hunting Party album, the US band rediscovered the heavy – as Metal Hammer found out when we caught up with the band in Los Angeles on the eve of their fourth and final headlining appearance at Download.

“If you don’t play well, you’re going to drown in piss and shit.”

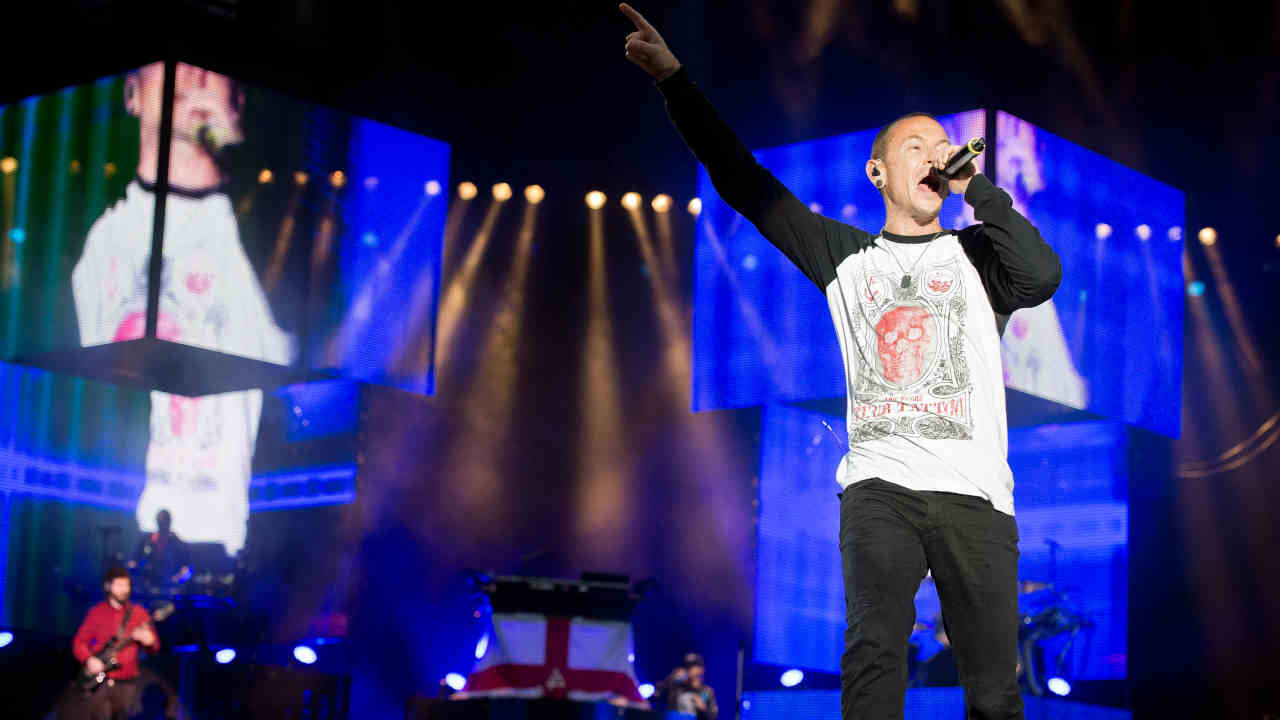

Not exactly the supportive advice a band wants to hear en route to a main stage appearance at Download, and yet as Linkin Park approached their inaugural headlining slot at the 2004 festival, singer Chester Bennington recalls that this is precisely the stomach-knotting caveat that they received. By that summer, the Southern California six-piece had already sold 10million copies of their 2000 debut, Hybrid Theory, a brawny mix of rap rock, electronica and nu metal.

While Meteora, their 2003 follow-up, tampered little with their commercially verdant blueprint, it reaffirmed the band’s unqualified mainstream appeal with a trio of stylish, radio-friendly singles – hardly the neck-breaking stuff that gets a thrash fan salivating. Yet there they were, headlining the first night of a Download bill that included scorched-earth metallers like Slipknot, Machine Head and Opeth, not to mention a little Bay Area lot called Metallica, who were headlining the second night. With their smooth amalgam of synth-driven rap rock and hooky, mainstream pop, could Linkin Park survive their set in front of one of the largest metal convocations on the planet?

Easygoing and self-effacing, Chester chuckles as he explains that evening’s battle plan to Metal Hammer: “I knew that, well, we better go out there and not fucking suck! That’s what we had to do!”

That set would prove a watershed moment for the band. Linkin Park not only did not disappoint, but that evening’s performance galvanised the band’s reputation as a ferocious live act capable of distilling their polished studio output into a punishing live set fuelled by muscular grooving and relentless rhythmic aggression.

This June, Linkin Park return for a fourth headlining slot at Donington on the heels of the release of their sixth studio album, The Hunting Party, and while the ensuing decade has seen the band shift more than 60 million albums and score two Grammys along the way, much of the head-scratching uncertainty running up to that 2004 appearance has resurfaced, primarily rooted in the scope of their more recent output.

With each album since Meteora, Linkin Park have steadfastly refused to rehash the primal menace of their debut and instead embarked on a trio of textured and experimental pop odysseys, their ambitions playing out in moody synths, grandiose atmospherics and bouncy flourishes of modern hip hop. By the end of 2013, it was deja vu: Linkin Park had come to enjoy a reputation as a well-heeled alternative pop act, so how in the world would they survive another set in front of the biggest metal audience on the planet?

Sitting down with the band in a bright loft on LA’s Santa Monica Boulevard, Linkin Park – Chester, rapper Mike Shinoda, guitarist Brad Delson, bassist Dave ‘Phoenix’ Farrell, drummer Rob Bourdon and DJ Joe Hahn – are relaxed and in high spirits for the latest of many photoshoots to promote the new release. None of the men betray the faintest concern over their impending return to Donington or their subsequent dates with Metallica and Iron Maiden. To a man, they radiate naught but enthusiasm and readiness for battle. Such unchecked confidence is due in no small part to the effusive reception that has greeted the first single, Guilty All The Same; a blazing modern rocker, seething with buzzsaw grooves, breakneck tempos and Chester’s screaming vocals. It was the last thing anybody expected out of a band who in recent years have arguably held more in common with Gwen Stefani than James Hetfield.

What inspires a group of successful musicians, all in their late 30s, to shift the creative course of a multi-million dollar enterprise and to charge in the opposite direction? According to Mike, the inspiration for The Hunting Party was far more visceral than a conscious attempt to tap into their earlier output.

“At a certain point I had created a handful of demos that I realised would fit in really well with alternative radio, like pop alternative,” he states. “Although I like to listen to that type of music and there are a lot of those bands that make great records, I realised that I like listening to them more than I like hearing us make music that sounds that way. It just wasn’t exciting to me and I didn’t believe in it any more.”

Mike wasn’t alone in his creative malaise. Although his band had already amassed electronic, dance-orientated tracks for the next record, the new material found all six men ambivalent and uninspired. It wasn’t that the songs were shoddy or substandard; quite the opposite. The first round of demos might have germinated into a viable, stylistic successor to their brooding 2012 release, Living Things. The problem, according to Rob, was that collectively the band had compared their current enthusiasm with that of their earlier efforts and glumly concluded, “This isn’t as exciting.”

Mike realised that it was time to hit the ‘reset’ button on Linkin Park. Discarding what they had already written, he gathered the band and laid out the framework for their next campaign. Chester recalls: “I think Mike’s exact words were, [assuming a dead-on Mike Shinoda impersonation] ‘So we’ve been working on these songs, and we’ve got about five or six of them, and I’ve decided that I fucking hate them. So I’m going to do something completely different and I’m going to show you guys a little taste and we’ll see what you think.’” Mike then played them the machine-gun intro to Guilty All The Same, and in Chester’s words, “When we heard the heavy stuff that came in, I was like, ‘Fuck yeah, dude!’ I haven’t been that excited about aggressive stuff for a while!”

For reference points, Mike pointed the others to bands like Refused, Helmet and At The Drive-In, even going back to older hardcore bands like Gorilla Biscuits and Inside Out – bands whose seismic force relied heavily on the bludgeoning riffage of their respective guitarists. This posed a thorny dilemma for Linkin Park, as their own guitarist, Brad, had grown less and less inspired to play his instrument over the course of their past few releases. In fact, much of the guitar parts on their recent albums were played by Mike and not Brad. Understanding that they could not write a great rock album without placing the guitar front and centre, Mike sat Brad down for the type of conversation that, in practically any other band, would surely end in shouting, fisticuffs and heated resignations.

“When the idea came to us to make this kind of a record,” Mike says, “I said to Brad, ‘Dave told me that when he met you in high school, you were the best guitarist that he had ever met. If I’m 14 years old right now and I listen to Linkin Park’s catalogue, do you think that that’s my impression? If it’s not, do you think that 14-year-old kid would be super-proud of you, or do you think he would say, ‘He’s kind of a pussy!’ How about on this record, you don’t do it for somebody else, do it for you? Do it for your 14-year-old. What can you write to inspire 14-year-old you to become a guitarist?’”

Rather than respond with hurt or indignation, Brad converted the blunt exchange into the inspiration for his most accomplished work to date: a blistering fretboard showcase that eclipses any of his contributions on the earlier records. Prior to meeting wth the band, Metal Hammer was treated to a private listening session of several unmastered tracks on the new album and on Keys To The Kingdom, All For Nothing and Rebellion. Brad’s guitar parts evoke the snarled swagger of contemporary shredders like Mark Tremonti or even Appetite-era Slash. While studio versions of these songs easily stand toe-to-toe with the best of Linkin Park’s early output, these guitar-driven beatdowns were clearly written with arenas in mind.

Although Dave is the most dyed-in-the- wool metalhead in the band, the guys routinely namecheck acts like Anthrax, Mastodon, Metallica and Deftones among their influences, and therefore they understand that “heavy” is a relative qualifier in the sprawling heavy metal landscape. Mike grins as he points out that as long as there is a Meshuggah, Linkin Park will not be releasing the heaviest album of all time. Nonetheless, they have recruited some high-profile guest appearances from a gang of grizzled veterans, including Helmet’s Page Hamilton, System Of A Down’s Daron Malakian and RATM legend Tom Morello, honing a sharp edge to the material that has been notably absent on their prior releases.

Heavy or not, when a band achieves the sustained commercial success of Linkin Park, questions understandably arise as to that band’s ability to reclaim the tension and authenticity of their early output. Chester admits that in the wake of Hybrid Theory, such expectations often proved suffocating. With the commercial dominance of the debut came the inevitable backlash from both critics and trolls; a virulent, if inevitable reaction for which Chester was entirely unprepared.

“We were really blessed with Hybrid Theory because it’s a fucking huge record and it was one of the biggest debuts ever. That’s great, but with that is the double-edged sword that do we now have to defend ourselves for the rest of our lives. Like, we’re really who we are! That was something that I struggled with very early on.”

While the band would eventually learn how to overcome the slings and arrows of detractors, they insist that they have never second-guessed the creative choices they have made.

“We stand behind every song,” says Chester. “Each record is a representation of the best work that we can do at that time, and with every record we try to stay excited creatively. We care about what we like and hopefully that translates to our fans and for the people who don’t like it, well, fucking go listen to something else.”

Hybrid Theory has sold 27million copies and to celebrate their 10-year anniversary of the first time they headlined Download, the band will play it in its entirety as part of their set during this year’s festival; a nod to the era when it all began and a bridge to their most ambitious album yet. What sort of connection do they see between these two bookends?

“This time,” Chester explains, “we wanted to write music that gets that 17-year-old who was never thinking about guitars to go, ‘I want to play guitar because of that song!’ We don’t want to remake Hybrid Theory. We want to make the album that makes the kids who are going to make the next Hybrid Theory. That’s what we want.”

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 258