On January 24, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the minute hand of the Doomsday Clock from 100 seconds to midnight to 90 seconds to midnight, reflecting their experts’ opinion about how much closer humankind has slid toward potential global ruin.

“The risk of atomic escalation in Ukraine brings the world closer to nuclear war than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Daniel Zimmer, a post-doctoral researcher at the Stanford Existential Risk Initiative, tells Inverse. “It makes sense that the hands would be moved up an additional ten seconds closer to midnight for 2023.”

Initially conceived during the height of the Cold War as a way of signaling to policymakers and the public just how close nuclear brinkmanship was bringing the US and Soviet Union to a disastrous nuclear war, the setting of the clock has more recently taken into account other potentially existential risks such as climate change and artificial intelligence.

But is a public relations metaphor conceived more than half a century ago still an effective device for communicating risk in the contemporary world? Was it ever?

Judging by the fact that the end of the Cold War did not lead to worldwide nuclear disarmament, and that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has once again raised the specter of global thermonuclear war, it may seem the Doomsday Clock never successfully conveyed the cautionary message the nuclear scientists behind it intended.

But on the other hand, the Doomsday Clock is not a formally constructed ritual or device of the state and is, in many ways, an accidental cultural artifact. It was not conceived as a means of ending the threat of worldwide catastrophe directly, and eventually evolved as a means to generate discussion — and headlines — just like the one you clicked on to read more about the Doomsday Clock.

The history of the Doomsday Clock

The history of the Doomsday Clock goes back to the late 1940s, when scientists concerned about the risks posed by nuclear weapons, including Albert Einstein, formed many organizations to lobby for safer nuclear policy, according to Stevens Institute of Technology historian of nuclear technology Alex Wellerstein.

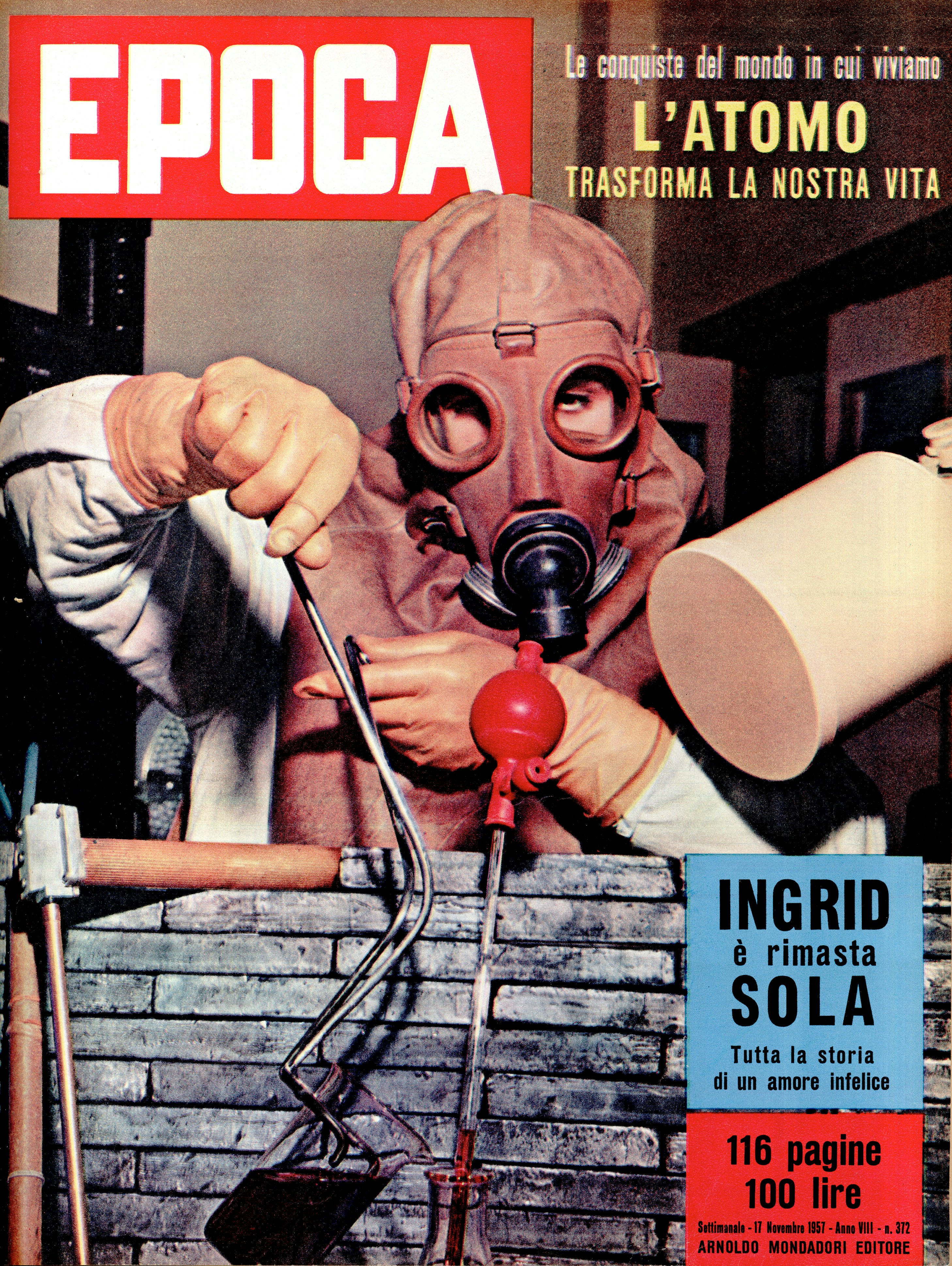

“One of these organizations, the Atomic Scientists of Chicago, had created a sort of small newspaper/magazine called The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists of Chicago, which became The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists as it became sort of more prominent,” Wellerstein tells Inverse.

For the first two years of its publication, The Bulletin was more like a newspaper, but in 1947, they commissioned Chicago artist Martyl Langsdorf to design a graphic cover, “an elegantly minimalist mid-century modernist layout that used six shapes (four circles and two rectangles) to suggest clock hands,” Zimemr says. The clock hands “were positioned at seven minutes to midnight to indicate urgency, but the initial calibration of the ‘clock’ was made for purely aesthetic reasons by the graphic designer.”

It wasn’t until 1948, when the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, that someone at The Bulletin had the idea to move the clock’s hands forwards to three minutes to midnight to reflect the occasion, according to Zimmer.

“They pushed it to two minutes to midnight in 1953 to register the increased threat posed by the new hydrogen bomb,” he says, “and then let it swing back and forth for the next 50 years as progress towards nuclear arms control advanced and retreated.”

The further from midnight and annihilation ever represented on the clock was at the close of the Cold War, in 1991 when The Bulletin rolled the minute hand back to 17 minutes from midnight.

Importantly though, it wasn’t until the 1970s that a group of scientists would meet to discuss the threat of apocalypse, nuclear or otherwise, and attempt to reflect the associated risk in the positioning of the Doomsday Clock’s hands. From its inception until about 1973, Wellerstein says, the clock’s time was dictated purely by Bulletin editor Eugene Rabinowitch, which is partly why you cannot draw a strict line between the Doomsday Clock and the exact level of risk at any time in history, particularly from the 20th century through today.

“Why didn't they change it in the Cuban Missile Crisis?” Wellerstein says. “Well, because it was one guy, and also the Cuban Missile Crisis happened before they had a chance to update it.”

It was once Rabinowitch died in 1973 that a team of scientists began setting the clock with an eye towards really getting a message out.

“It starts off as just pure aesthetics and then becomes this sort of very conscious way in which the Bulletin and its advisors are trying to sort of intervene in the world,” Wellerstein says. By the 1980s, “there’s newspaper articles about it, there’s political cartoons about it. It’s featured in Alan Moore’s Watchmen. It becomes this sort of cultural commodity.”

Does the Doomsday Clock work?

If The Doomsday Clock was at its height as a cultural commodity in the 1980s, what about its cultural and political impact? It’s impossible to say whether and how much the existence of the clock may have influenced or catalyzed, say, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty talks begun under President Ronald Reagan and signed in 1991. There are too many factors. And Wellerstein points out no single public awareness campaign has ever fixed a global problem all on its own.

“It's just not the case that any organization or any person, however prestigious, can simply say, ‘hey guys, the world is in a bad place. Could you please fix it?” he says. “The problems are too big. The world is too complicated.”

But it may be helpful to remember, Wellerstein adds, that the Doomsday Clock is not a scientific instrument or even an institution. It’s a metaphor and a communication tool. One reasonable measure of success might simply be whether people talk about it when the time changes, and the issues behind that change.

“Is it getting articles written about? It seems to be,” Wellerstein says. “Is it producing, I don't know, public outcry and radical change? I mean, it never has.”

Doomsday today

If you’re going to pay attention to the Doomsday Clock, one way to think of it is as a measure of how the world’s leaders are responding to global risks in a given moment, rather than a measure of when catastrophe might strike, according to Simon Beard, the academic programme manager for the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge University.

“The very late setting of the clock now, in my view, is justified not because the current geopolitical situation is necessarily worse than it was during the Cold War,” Beard tells Inverse, “but that it is nevertheless further from what is needed because the actual level of global cooperation needed to deal with all of the existential risks facing us is higher.”

It’s not just the risk of a US-USSR nuclear exchange anymore, Zimmer points out, though the war in Ukraine has certainly reignited that possibility. Nuclear weapons have proliferated into more hands, very little of practical value has been done to even begin to arrest climate change in time to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, “and perhaps most dispiritingly, after the millions of lives lost and epochal disruption to daily life caused by Covid, astonishingly few resources are being allocated for future preparedness for a naturally occurring pandemic,” he says.

So while there is a risk of inuring people to the movements of the Doomsday Clock’s hands by keeping them so close to midnight — a problem switching from minutes to seconds may help, Zimmer adds — “it’s not wrong in itself for the clock’s hands to be stuck where they are,” he says. “If we’ve grown psychically numb to that fact, that’s on us.”

Good news at the brink

The very fact that people can become inured to the message of the Doomsday Clock is both a risk and a sign of a potentially positive trend. If people are at risk of being burned out on messages that the world faces grave risks, it at least means people are, in fact, aware of those risks. There are now academic centers like those of Beard and Zimmer dedicated to researching existential risks and how they can be mitigated.

If you need to motivate people to act to prevent disaster, it may be preferable to find a way to move those who are aware and flirting with fatalism rather than reach many who have no clue of the dangers.

“For me, the most important thing to remember — whichever risk you’re looking at — is that, miracle of miracles, we’re still here despite all the existential risks that we’ve already done to date,” Zimmer says. “This means we still have time to turn things around, no matter how late the hour.”