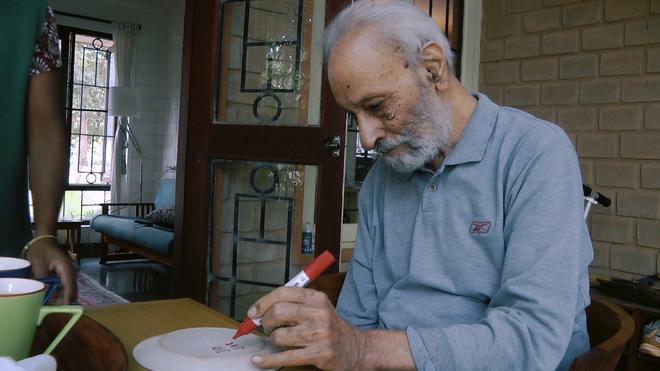

A frail old man leans heavily on his cane as he makes his way to a garden chair under a spreading tamarind tree. Those gnarled hands once held a hockey stick, those stooped shoulders once wore the rank of Commander in the Indian Navy. Grahnandan Singh or Nandy Singh was an old boy of Government College, Lahore, champion hockey player from the Punjab province of undivided India, Partition survivor, two-time Olympian, and keeper of a friendship that survived in the deep recesses of his heart for nearly 60 years.

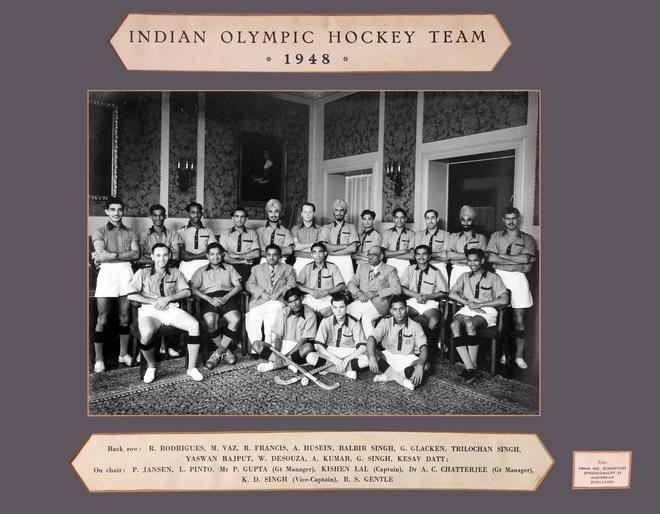

“My father was a member of the Indian hockey team that won the gold in the 1948 and 1952 Olympics. But I missed out on knowing him when he was a champion. It was only when he was fighting to stay afloat after a stroke that I met the champion,” says Bani Singh, Nandy’s daughter and the director of Taangh that was recently screened at Periyar Thidal as part of the 10th Chennai International Documentary and Short Film Festival.

Seated under a tree, with the screech of parrots punctuating the breezy afternoon, Bengaluru-based Bani, a graduate in industrial design from NID, and part of the team that set up the Virasat-e-Khalsa Museum in Anandpur Sahib, says, “My parents’ memories are important because they underpin mine. Subconsciously, I was looking for the missing pieces, the years my parents never spoke about, the stories now being retold and repackaged in their country and ours.”

Those stories lay lost in the murky bloodbath that followed the cleaving of the Indian subcontinent into India and Pakistan. This was a time when things fell apart – homes, relationships and identities – among them the lives of four college boys who played hockey together but had to choose sides.

“From the story of how the Indian team, within a year of independence, beat Britain to win gold at Wembley, Taangh slowly became the story of a friendship that even Partition couldn’t break,” says Bani, adding that the only advice Nandy had for her was to go meet his buddies.

So Bani travelled to Delhi and Kolkata, Mumbai and across Punjab, meeting the charming Keshav Datt and the stoic Balbir Singh. “When my father passed away in 2014, there was a lot of footage. But for two years I didn’t work on it as it was too personal. It was a gigantic jigsaw puzzle that needed repeated editing.”

Taangh goes beyond the muscle-flexing drills of hockey players. While it has its sepia pictures from newspapers and scrap books, and footage garnered from both Films Division of India and National Film Archive of India that shows nimble stickwork and men in blazers celebrating their wins, it also dovetails into its saga Shahzada Shah-Rukh of Pakistan who won Olympic fame both as hockey player and cyclist and was a dear friend to Datt and Nandy.

“When Keshav uncle wistfully mentioned Shah-Rukh’s name and how he had saved him during Partition riots, I hurried back to ask my father what he remembered. When he teared up, I realised here was a story of friendship and love that had to be told. My father had never gone back to Lahore but I was keen to meet Shah-Rukh before it was too late,” says Bani, who took a 50-minute flight to Lahore but journeyed an immeasurable emotional distance to meet the elusive friend.

Taangh beautifully captures the child-like joy that Shah-Rukh exudes when he meets Bani, his kissing the photograph of Nandy and Datt and playfully calling him “badmash”, the honour that the alma mater of these men – Government College Lahore - extends to Bani by hosting a hockey match to celebrate these Olympians, and the engraved memento they send across as a physical connection to a time gone by.

The 90-minute documentary travels next to Kolkata People’s Film Festival and Film Southasia in Kathmandu. Bani hopes this will open screenings in Pakistan.

This daughter’s journey into the complex realms of home and nation, victory and loss, is also a journey into the heart of an extraordinary friendship.

“My father’s life happened to be part of a historic canvas that was so momentous. Making Taangh was personal, but I hope its larger story means something to the next generation.”