Dinosaurs are in the news these days, but it’s not just for groundbreaking discoveries.

More and more paleontologists are ringing alarm bells about high-profile auctions in which dinosaur fossils sell for outrageous sums. The most recent example involves a 77 million-year-old Gorgosaurus skeleton that Sotheby’s sold for over US$6 million in August 2022.

But that’s not even close to the most anyone ever paid for a dinosaur. In May 2022, Christie’s sold a Deinonychus skeleton for $12.4 million. And a couple of months before that, Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism paid an eye-popping $31.8 million for Stan, a remarkably complete T. rex from South Dakota’s Hell Creek Formation that’s going to be the centerpiece of the Persian Gulf city’s new natural history museum.

Some scientists are so dismayed they are speaking out. University of Edinburgh paleontologist Steve Brusatte told the Daily Mail that auction houses turn valuable specimens into “little more than toys for the rich.” Thomas Carr from Carthage College in Wisconsin was even more forthright, saying, “Greed for money is what drives these auctions.” He also complained that wealthy elites – including actors Nicholas Cage and Leonardo DiCaprio – are competing to acquire the best specimens in a game of juvenile one-upmanship, describing them as “thieves of time.”

Most commenters trace the booming market for dinosaurs back to Sue, the largest and most complete T. rex ever found. After the FBI confiscated it from the same group of fossil hunters who found Stan, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago acquired it – with financial backing from Disney and McDonald’s – for over $8 million in 1997.

But as I document in my recent book, “Assembling the Dinosaur,” the commercial specimen trade is as old as the science of paleontology itself. And its history shows the debate over whether dinosaurs ought to be bought and sold involves much deeper questions about the long-standing but hotly contested relationship between science and capitalism.

Two sides of the debate

Paleontologists have good reason to oppose the commercial sale of valuable fossils. Science is fundamentally a community enterprise, and if specimens aren’t available for public examination, paleontologists have no way to assess whether new findings are true. What if a particularly outlandish theory is based on a fraudulent specimen?

This happens more often than you’d think. In the late 1990s a private collector purchased what appeared to be a feathered dinosaur at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show. National Geographic subsequently reported on it to great fanfare, claiming it was a “missing link” between dinosaurs and modern birds. When scientists grew suspicious, they found that the so-called “Archaeoraptor” fossil combined pieces of several distinct specimens to make a chimerical creature that never existed.

But commercial fossil hunters make a compelling point, too. Most fossils first come to light through the natural process of erosion. Eventually, however, erosion also destroys the specimen itself – and there simply aren’t enough scientists to find every fossil before it is lost. Hence, the argument goes, commercial collectors should be celebrated for saving specimens by digging them up.

Wealthy philanthropists distance themselves

Both sides of the argument make a compelling point. But as the fiasco around “Archaeoraptor” reveals, it’s worth asking whether financial incentives erode trust.

Dinosaurs first came to the attention of geologists during the 19th century. In fact, these gigantic lizards did not acquire their name until the comparative anatomist Richard Owen invented the biological category “Dinosauria” in 1842.

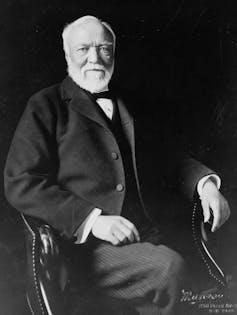

At that time, scientists did not treat dinosaurs any differently from other valuables that could be dug out of the ground, such as gold, silver and coal. Museums purchased most of their fossils from commercial collectors, often using funds donated by wealthy industrialists like Andrew Carnegie, who even had a dinosaur named after him: Diplodocus carnegii.

That started to change at the very end of the 19th century, when there was a concerted effort to decommodify dinosaur bones, and museums began to distance themselves from the commercial specimen trade.

One impetus came from museums’ wealthy benefactors, who sought to demarcate their charitable activities from the unsavory world of commerce. Philanthropists like Carnegie and J.P. Morgan gave money to cultural institutions because they wanted to signal their refined taste, their appreciation for learning and their republican virtues – not to enter into a business transaction.

Moreover, the first Gilded Age resembled the present in that it, too, saw a sharp increase in economic inequality. This led to widespread class conflict, which could be remarkably violent and bloody. Afraid that incendiary labor leaders would bring the industrial economy to its knees, wealthy elites began using public displays of conspicuous generosity to demonstrate that American capitalism could yield public goods in addition to profits.

For all these reasons, it was essential for their philanthropic activities to be seen as selfless acts of genuine altruism, utterly divorced from the cutthroat competition of the marketplace.

Scientists take control

At the same time, paleontologists embraced the language of “pure science” to claim they produced knowledge for its own sake – not financial gain.

By arguing that their work was free from the corrupting influence of money, scientists made themselves more trustworthy.

Ironically, scientists found they could attract more funds by claiming to be completely uninterested in money, fashioning themselves into ideal recipients for the philanthropic largesse of wealthy elites. But that further necessitated a clear demarcation between the the culture of capitalism and the practice of science, which entailed a reluctance to acquire specimens via purchase.

As scientists began shunning the commercial specimen trade, museums set about using the generous donations of wealthy philanthropists to mount increasingly ambitious expeditions that allowed scientists to collect fossils themselves.

Dinosaurs in the New Gilded Age

But their ability to control the private market for dinosaur bones did not last forever. With the United States in the middle of what some call a New Gilded Age, it has come roaring back.

Today, the most spectacular dinosaur fossils often hail from the Jehol formation of northeastern China. And more often than not, they are purchased from local farmers who supplement their incomes by hunting for fossils on the side.

As a result, the question of whether commercial incentives erode trust is back with a vengeance. Li Chun, a professor at Beijing’s prestigious Institute for Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, estimates that more than 80% of all marine reptiles on display in Chinese museums have been deceptively altered to some degree, often to increase their value.

The age-old worry about whether the profit motive threatens to undermine the values of science is real. But it is hardly unique to paleontology.

The spectacular implosion of Theranos, a tech startup that secured more than $700 million in venture capital based on false promises of having developed a better way to conduct blood tests, is just just a particularly high-profile example of commercial deceit paired with scientific misconduct. So much scientific research is now being paid for by people who have a commercial stake in the knowledge produced – and you can see the ramifications in everything from Exxon’s decision to hide its early research on climate change to Moderna’s recent move to begin enforcing its patent on the mRNA technology behind the most effective COVID-19 vaccines.

Is it any wonder that so many people have lost trust in science?

Lukas Rieppel has received funding from the National Science Foundation and the Mellon Foundation, among others.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.