Wildlife in the Loop usually includes just pigeons and rats.

But a family of federally protected Peregrine falcons has made a temporary home there.

In the last week, they have been dive-bombing pedestrians passing below their seventh-story nest at an office building on Wacker Drive.

Chuck Valauskas was leaving work last Thursday, walking below the nest at 100 S. Wacker, when he felt a thud against his head.

“I thought, ‘What was that?’ It felt like a 16-inch softball,” Valauskas, a patent attorney from Edison Park, told the Sun-Times.

He looked down for clues, but then heard a squawking falcon perched above him. Another falcon fluttered nearby, watching from above the Chicago River.

“It dawned on me what the term ‘wingman’ meant,” he said.

He suffered a 1-inch gash on his head and got a tetanus shot to be safe. He now avoids the path beneath the falcon nest along the river, cutting through the building instead.

At least one other person has been bopped by the birds, according to security staff at the building.

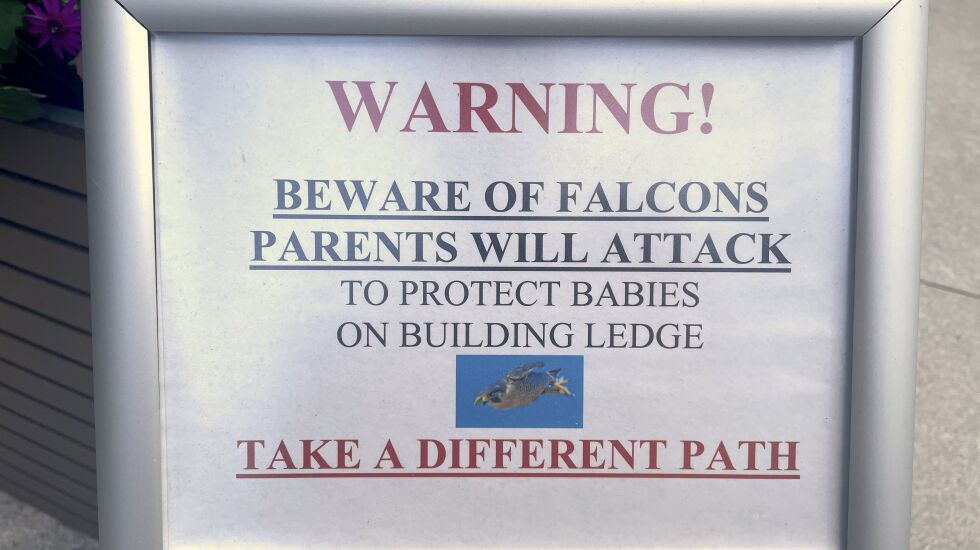

After the attack, management of 100 S. Wacker placed two signs on the path along the river.

“Warning! Beware of falcons. Parents will attack to protect babies on building ledge. Take a different path,” the signs read.

Near the sign lay bird droppings and bird feathers from prey that had fallen victim to the falcons.

Most commuters who spoke with a reporter Thursday said they hadn’t noticed the birds perched seven floors above.

Ruben Guardiola has been monitoring the falcons for a couple of weeks from his 10th-floor office window at the building just south of the nest.

He noticed the raptors becoming aggressive with passersby after their chicks showed up last week. The birds have appeared to calm down over the last few days, he said.

He’s snapped photos of the chicks warming up in the sun of the seventh-floor ledge.

“Look at the building. It’s built for” birds, Guardiola said. “There’s no people, no predators, and there’s lots of vertical horizontal space.”

Falcons have been nesting every spring at the building since at least 2016, according to Mary Hennen, who leads the Peregrine program at the Field Museum.

Peregrines used to nest on higher floors there. But the birds this year have nested low enough that they’ve become aggressive to humans walking below.

“It’s just a momma protecting her young,” Hennen said. “Their reflex is to swoop at you. That’s on purpose, to scare you.”

She’s noticed three chicks and two adults at the building. The falcons may leave in a few days or weeks, as soon as the chicks learn to fly, she said.

Peregrine falcons nearly went extinct in the middle of the last century after the widespread use of pesticides, mainly DDT, poisoned the birds. The raptors ingested insects laced with the deadly chemical and laid eggs too thin to sustain their offspring until hatching.

Since then, the Peregrine population has surged “beyond historic levels,” said Hennen, thanks to persistent conservation efforts by birders beginning in the mid-1980s. The birds were taken off the endangered species list in 1999 and remain federally protected.

Peregrines are known as one of the fastest birds, able to reach speeds in excess of 200 mph when diving.

The resurgence of birds along the river is the latest sign that wildlife is finding a more hospitable environment in the city.

In the past year, Chicago has welcomed a family of foxes at Millennium Park, the offspring of piping plovers Monty and Rose at Montrose Beach, and the massive snapping turtle “Chonkosaurus” along the North Branch of the Chicago River.

“I think it speaks volumes about the river, because this used to have nothing living in it,” Guardiola said. “The fact that we’re getting fish and turtles and stuff back in the river [shows] there’s something for them to eat.”