The only way to tackle our economic, social and environmental failures is by deep systemic change – and despite this week's international plaudits for the state of our democracy, that's something we really struggle with.

Opinion: Thursday morning showed us two marks of New Zealand democracy: Police arrested some protesters and removed others from the grounds of Parliament; and New Zealand rose from fourth to second in the annual global democracy index.

Are there connections between the two? Yes, some.

Are they strong enough to help us meet our great housing, social, economic and environmental challenges? No way.

Despite our high ranking, our democracy needs a major overhaul, as do democracies the world over.

Democracy is fading worldwide, exacerbated two years running by the pandemic. In its latest index, the Economist Intelligence Unit judged only 21 countries were full democracies. They represented only 12.6 percent of countries, and 6.4 percent of the global population.

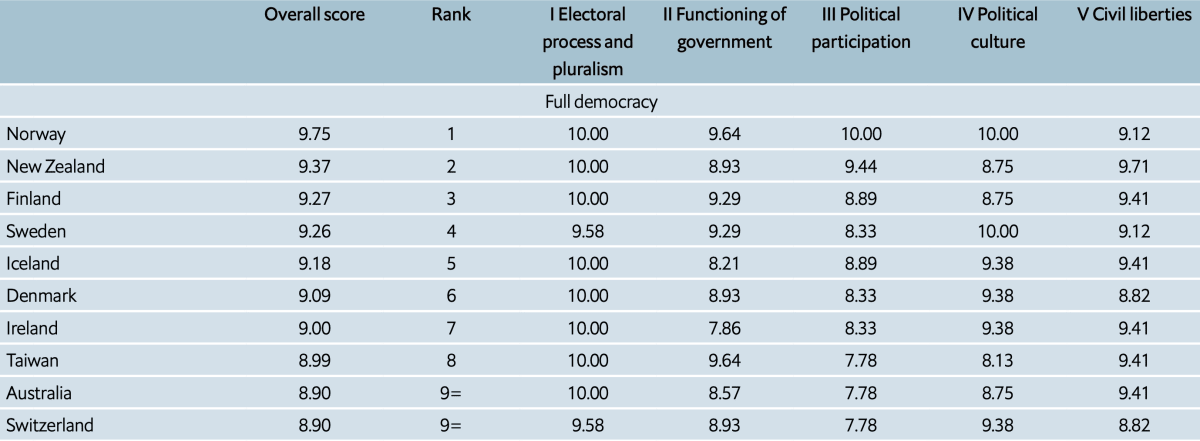

Top 10 democracies

Behind this elite group, comes a large cohort of 21 Flawed Democracies. They represent 31.7 percent of countries and 39.3 percent of the global population. Notably, the US was downgraded from full to flawed democracy in the 2016 index. It fell further in the 2021 index, just released. It now ranks 26th in the world with its overall score falling to an average of 7.85 out to 10 across the index’s four categories, from 7.92 a year ago.

New Zealand is now second after Norway. Our rise from fourth over the year was driven by one category: Political Participation rose to 9.44 from 8.89. The other three were unchanged – Electoral Process and Pluralism at 10; Functioning of Government at 8.93; Political Culture at 8.75; and Civil Liberties at 9.7.

Political Participation is scored on nine factors ranging from voter turnout in national elections and membership of political parties and political NGOs to citizens’ preparedness to participate in lawful demonstrations and the extent the adult population follows politics in the news.

Sadly, the EIU did not give countries’ scores on individual criterion. But one way or another we upped ours in this category last year. However, our score on Political Culture was somewhat lower than for other high-ranking countries, a point I’ll return to later in this column.

The protesters who converged on Parliament this week were angry about a wide, jumbled and sometimes contradictory range of issues from vaccines and pandemic restrictions to the closure of the Marsden Point fuel refinery and alleged media corruption.

As the EIU noted in its democracy report: “The pandemic has had a negative impact on the quality of democracy in every region of the world, but some regions have fared far worse than others, with Latin America having suffered especially badly.”

The disinformation and divisions coursing through this week’s protest and others here is fuelled by many factors, of which social media is a very powerful one. That’s true worldwide. Protest being far less inflamed or extensive here so far than in many other countries is no comfort. It will only get worse if we fail to improve relationships and understanding.

Having a small population will help us, as it does with other smaller countries. Of the top 10 democracies, the four most populous are Australia (26 million), Taiwan (24m), Sweden (10.4m) and Switzerland (8.7m).

So, yes, there are connections between the two marks of our democracy we saw on Thursday, both in its weaknesses and its strengths.

Yet, our democracy has still failed us over the past two decades or more. We have a long legacy of worsening issues to sort out. The latest diagnosis is the OECD’s recent annual report on New Zealand.

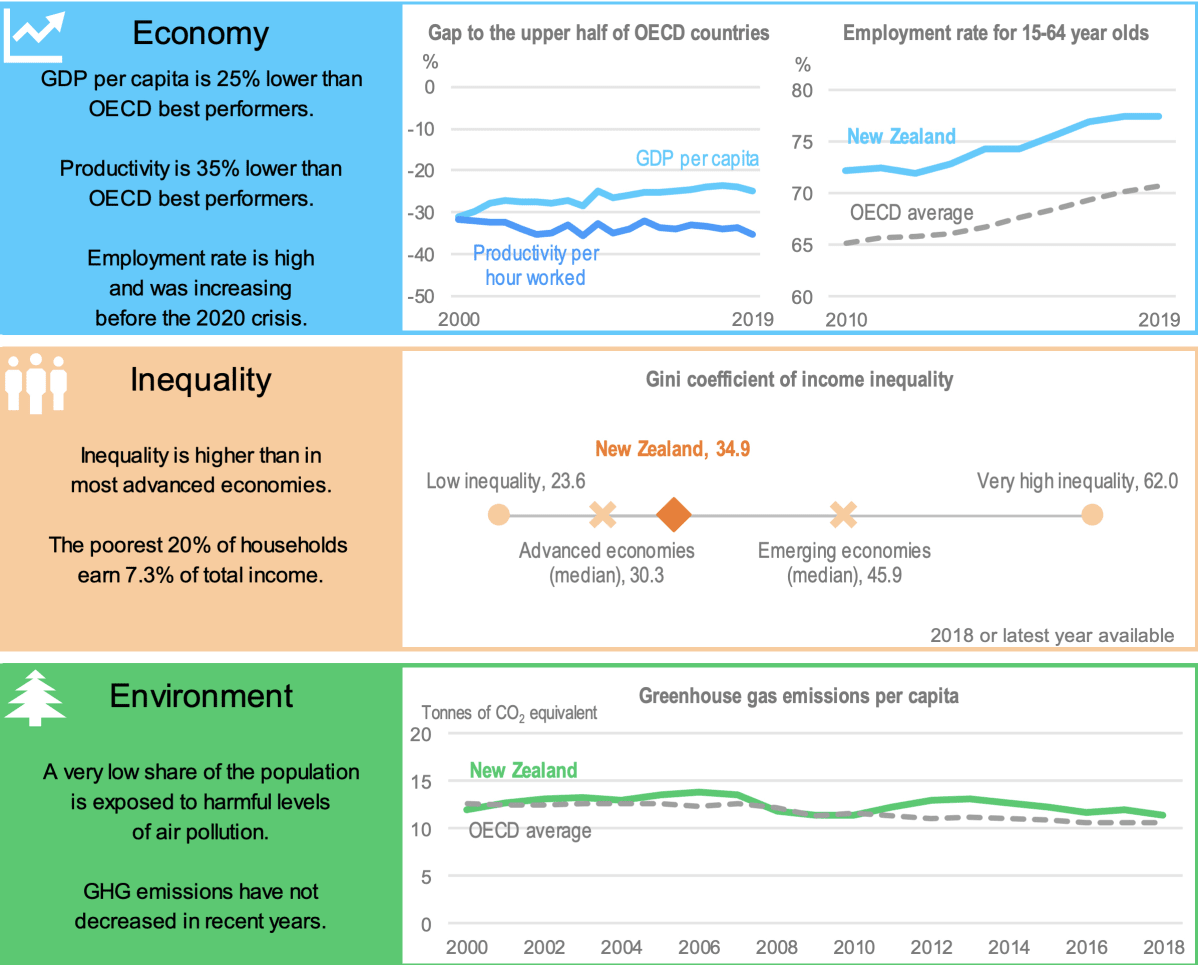

Some of our biggest failures are summarised in these two charts from the report. The first is the OECD’s verdict on our three biggest areas needing reform to address our low GDP per capita and low productivity; our inequality; and our poor environmental record (using greenhouse gas emissions as a proxy).

OECD: NZ’s 3 big areas of reform

Note that two of those charts span 20 years; and how little progress we made on those economic and environmental measures.

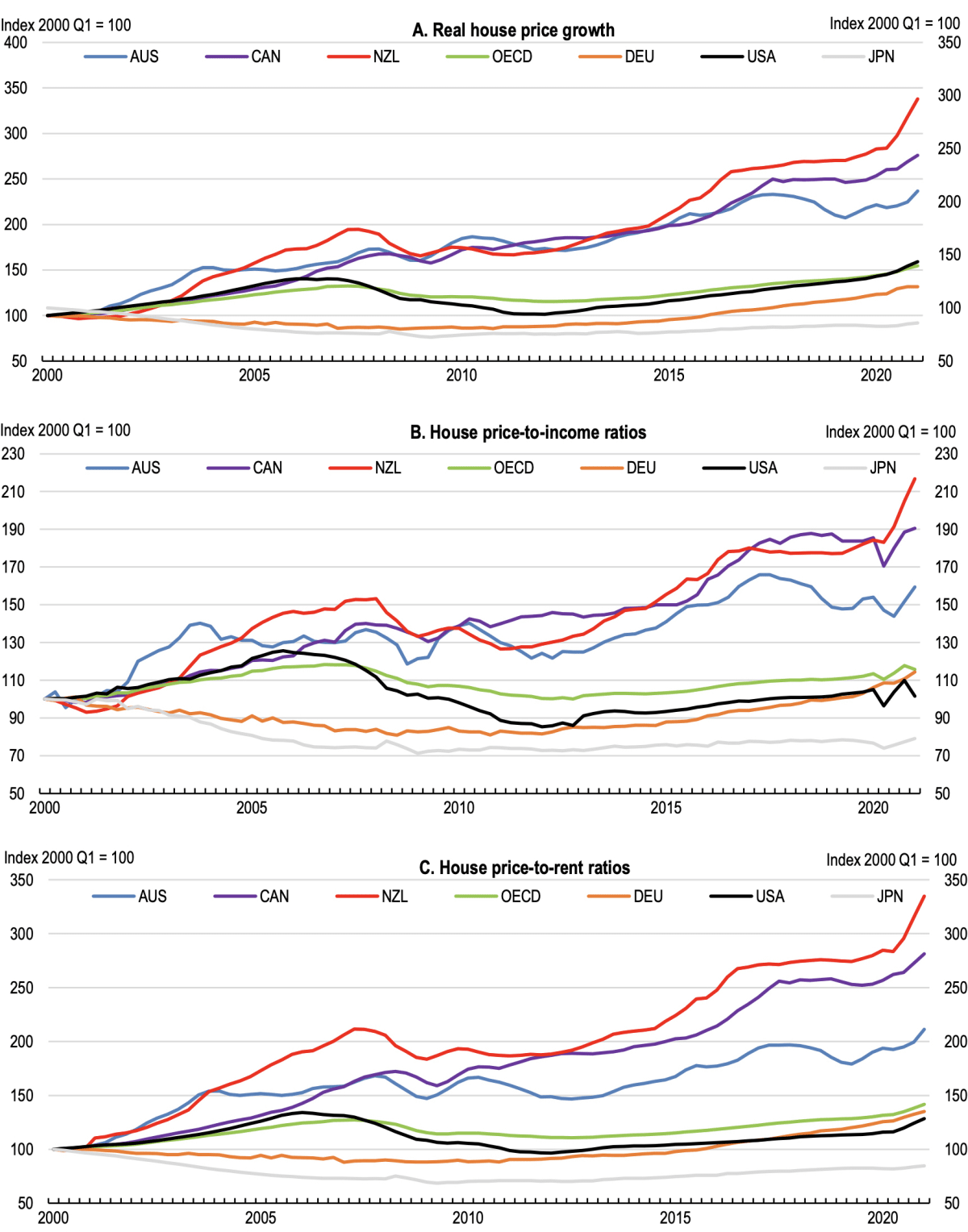

The other set of charts covers three measures of housing. Over the past 20 years our house prices have risen twice as fast as the OECD average and faster than other grossly over-priced markets such as Australia and Canada; ditto our house price-to-income ratio and our house price-to-rent ratio.

Real house prices increase more than other OECD countries

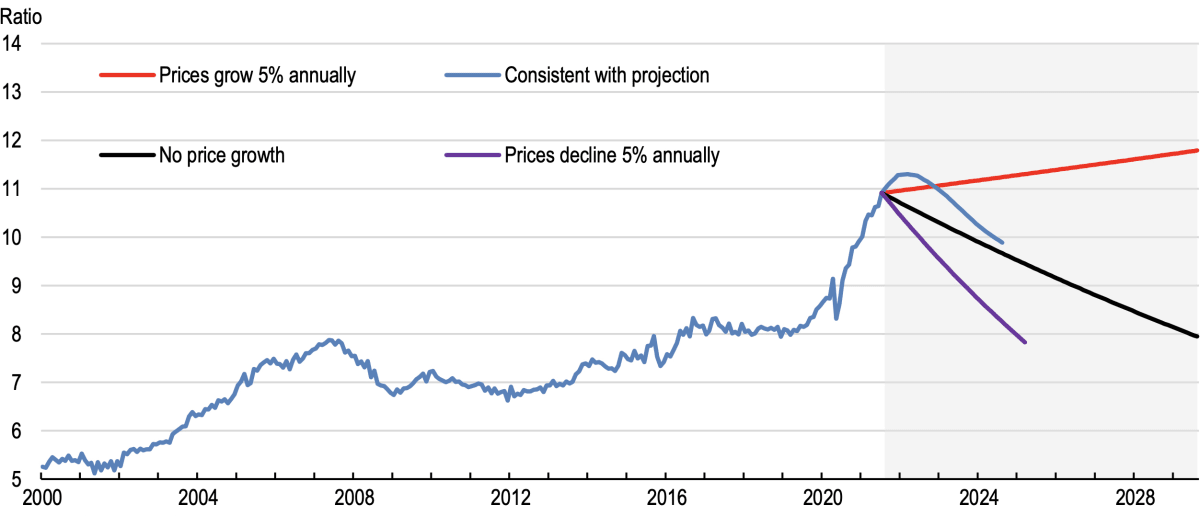

Our Prime Minister is promising to fix this, as did her two National Party predecessors. And like them, she expresses no goal for that correction, not even using the most fundamental measure – prices. Yet whatever the remedy such as stagnant house prices, gently falling prices or rising incomes we have a very long wait. The OECD captured that in this chart, based on Reserve Bank of NZ analysis:

It will take many years for house price-to-income ratio to return to pre-Covid levels

So, what is our Labour Government going to do about all these issues, and many more? Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had an opportunity to tell us on Tuesday when she delivered a speech at Parliament’s annual opening on her government’s plans for 2022.

She devoted two-thirds of her 2,895-words to the pandemic and related health issues. Beyond that she spoke barely 150 words on housing, 300 words on climate, and 500 on the economy. She announced nothing new or impactful. No surprise, her media team didn’t post it on the Beehive website. But should you wish too, you can read it in full in Hansard online.

In reply, Chris Luxon, National Party leader, delivered an even longer (3,462 words) and even more vacuous speech. As Peter Dunne notes in his latest Newsroom column, National in its 86-year history to date has essentially had only one idea – criticise Labour government initiatives then quietly keep them largely in place when it takes over government.

Of course, Parliament in particular, and our political culture in general, can deliver brave, principled and effective reforms. But most of those have been of human rights, treaty and other such societal issues.

We have really struggled, though, to conceive, plan and execute deep systemic change, let alone get as many people as possible involved in that and benefiting from it. But that’s the only way we’ll tackle our deeply rooted economic, social and environmental failures.

To do so, we’ll need to learn some new democratic practices, some new political culture. There are encouraging examples here and abroad. I’ll explore some from time to time in this column because our future depends on them.