I have experienced a few eureka moments in my career – usually the result of sheer luck or serendipity. In late 2021, I was part of the Editing Burns in the 21st Century team working on the new Oxford University Press edition of the Complete Works of Robert Burns. I had been granted rare access to the collections of Barnbougle Castle on the Dalmeny Estate by the River Forth, near Edinburgh.

Many will recognise the castle as the setting in the film The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, starring Maggie Smith. The materials there had been assembled by former prime minister (1894-5) and Earl of Rosebery, Archibald Primrose, who was a formidable historian and leading expert on the Scottish bard.

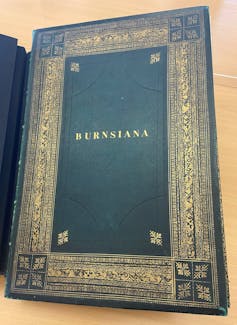

Working through the material at Barnbougle, our team made a number of finds, including at least one new manuscript. More than satisfied with our excellent pickings, we were packing up to leave when our host Lady Jane Kaplan, great granddaughter of Rosebery, asked if we would like to look at one more item. This was an album marked “Burnsiana”, which had been acquired in the 1890s, but had not been subject to outside scrutiny since.

When I opened it, I found it difficult to believe what I was seeing: there among the contents was page after page of listed building materials for Burns’s first marital home and farm-steading at Ellisland in Dumfriesshire.

These domestic items were listed with prices from Burns’s builder, Thomas Boyd. For example, there were details of 500 dozen roof-slates and their sizes; doors; windows with frames and their dimensions; silk cords; the items bought for the construction of presses (cupboards) in the bedroom and elsewhere; joists; screws; lintels; flooring and so on. The lists also contain quantities of thread, plates, buttons, beer and other items for the domestic economy.

Now this detailed ledger will help historians reconstruct the poet’s beloved farm as it was when he and his family first lived in it.

Burns’ beloved Ellisland

The spectacularly beautiful setting by the River Nith immediately inspired the bard on first viewing, and he decided to build a farm there for his wife Jean Armour and their young family. Burns occupied Ellisland from 1788-91, writing around a quarter of his entire output there, including his greatest hits Auld Lang Syne and Tam o’ Shanter.

I would have understood the significance of these domestic lists even if I had not been secretary of the board of trustees at Ellisland since 2020. However, in this role I was particularly aware that Burns’s farm had been gifted to the nation in the 1920s, having been in private hands until then.

Unquestionably Rosebery himself would have understood what he was looking at, but the material actively takes on the significance it has, chiefly because Ellisland became a heritage site and tourist attraction a century ago.

Over the years there has been much speculation about precisely which parts of the several buildings Burns had a direct hand in, and there are many questions too about the interior of the main farmhouse, which has been much remodelled since the Burns family inhabited it.

Thanks to the incredible detail contained in this new material, we will be in a position to re-imagine the interior of Burns’s farmhouse with much greater accuracy. Not only will the new information allow forensic historical architectural investigation, it also raises exciting possibilities in the context of the new XR (extended-reality computer reconstruction) of Ellisland.

The timing of the discovery is fortuitous too, as the Robert Burns Ellisland Trust has been involved in a series of extensive developments for the site over the past three years, and has begun to garner considerable project funding.

What better way to celebrate Burns Night this year than with this cache of historical detail that opens up Burns’ domestic life in the rural home he loved so much.

Gerard Carruthers has received funding for his work from AHRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.