Of all the rivers in the world, the St. Lawrence River is undeniably one of the most challenging for mariners.

This water highway is at some spots as narrow as a large river and, at others, as wide as a small sea. It has played a vital role over the last three centuries as an important artery for trade, communication, transportation and settlement. And since 1959, the year the St. Lawrence Seaway was inaugurated, it has been a gateway to the heart of the continent.

This article is part of our series, The St. Lawrence River: In depth. Don’t miss new articles on this mythical river of remarkable beauty. Our experts look at its fauna, flora and history, and the issues it faces. This series is brought to you by La Conversation.

The first European explorers who sailed the St. Lawrence discovered it was not easy to master: it was long, but never calm. After crossing the Gulf, mariners would face many difficulties navigating up the river to Québec City, including narrow, sinuous channels, shallow waters, shoal deposits and strong tides. Currents are sometimes unpredictable, there can be very dense fog, and, of course, the river is impossible to navigate in winter. No one ventured on its waters from the end of November to the beginning of May.

Qualified maritime pilots are a must on the capricious and indomitable St. Lawrence, which has the reputation of being one of the most difficult rivers to navigate in the world. The risk of collisions, groundings and shipwrecks is high, which led to tightened navigation safety regulations, particularly in response to the accidents involving large ships that occurred in the 1960s.

It is estimated that there are several thousand wrecks below the surface of the river.

As a doctoral student in geographic sciences at Laval University and president of the Technical Wreck Divers of Québec (PETQ), I propose introducing you to the three most important shipwrecks in terms of size that took place in the river. Our diving activities push the very limits of exploration. Notably, we use diving techniques adapted to the particularly restrictive underwater context of the St. Lawrence, with its strong currents, often reduced visibility and cold, black water, among other hazards.

Our expeditions allow us to share the passion of diving by exposing the results of our research and discoveries, while making the public aware of the history and hidden relics that are just a few steps from the shore of the river.

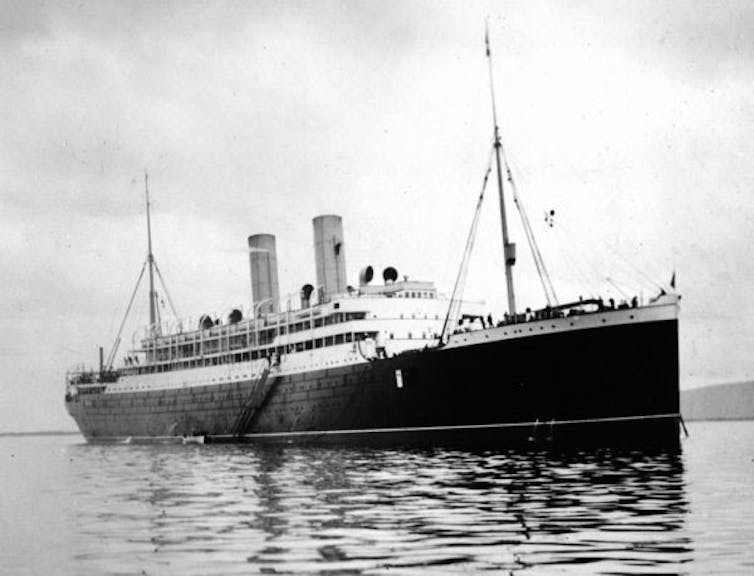

The tragedy of the Empress of Ireland (1906-1914)

Because of its magnitude, one shipwreck in the St. Lawrence River cannot be overlooked: the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Empress of Ireland. With its 1,012 victims, there is no question this disaster strikes the popular imagination.

This tragedy was the result of the ship colliding with the Norwegian coal carrier Storstad during the night of May 29, 1914, off Sainte-Luce, east of Rimouski, during foggy weather. In as little as 14 minutes, the liner sank in the cold and inhospitable waters of the St. Lawrence. Unlike the much publicized sinking of the RMS Titanic two years earlier, the worst tragedy in Canadian maritime history was quickly overshadowed by the outbreak of World War I.

It was only 50 years later, in 1964, that the wreck was discovered by a group of divers. Although gigantic, at 173.8 metres in length, this Edwardian liner, built in 1906, was not the largest to have sunk in the waters of the St. Lawrence.

SS Bulk Carrier Leecliffe Hall (1961-1964)

At 222.5 metres long and 23 metres wide, the Leecliffe Hall ranks first among the largest wrecks in the St. Lawrence River.

Built by the Scottish shipyard Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Ltd. — the same yard as the RMS Empress of Ireland — and launched in Port Glasgow on May 18, 1961, this colossus was an impressive 18,071 gross registered tons (GRT). The ship’s length from stern to bow is the equivalent of two American football fields glued together.

On Sept. 5, 1964, in the middle of a foggy day, the ship, loaded with 24,500 tons of iron ore, collided with the Greek freighter MV Apollonia off Île aux Coudres, in Québec’s Charlevoix region. The ships remained stuck together and did not sink.

The crew members were evacuated, safe and sound. But some of them, a few hours later, voluntarily returned to the ship, which was drifting alone, to attempt a rescue in extremis. While the men were in the midst of trying to regain control of the ship, the hull suddenly broke apart, killing three brave sailors. Two of the three bodies were never recovered. The Apollonia escaped with a badly damaged bow, but was able to sail again.

On Sept. 9, 2017, a little less than two years after our divers first visited the wreck, a commemorative ceremony was held at the Charlevoix Maritime Museum. In the presence of the widow of one of the missing sailors and some descendants of the other two victims, the ship’s bell and the builder’s plate, which had been recovered the previous year by our team and declared to the Receiver of Wreckage (a federal official whose key role is to act as the custodian of a wreck in the absence of the rightful owners, were handed over to the museum in an effort to maintain the collective memory of Charlevoix’s subaquatic heritage.

The ore carrier MV Tritonica (1956-1963)

At 161 metres long and 12,863 GRT, the MV Tritonica, built at the English shipyard Laing James & Sons Ltd. was the first ore carrier to use the St. Lawrence Seaway.

Sunk on July 20, 1963, off Petite-Rivière-Saint-François, in Charlevoix, following a collision in foggy weather with the SS Roonagh Head, the ship is the third-largest wreck on the St. Lawrence River in Québec waters.

In the silence of the night, locals in the village of Petite-Rivière-Saint-François heard the sounds of engines and sirens, and many, the metallic crash of the two ships colliding. The sinking cost the lives of 33 sailors, mostly Chinese. This was the greatest civilian maritime tragedy of the 20th century on the St. Lawrence since that of the Empress of Ireland.

In the days following the disaster, bodies were recovered from the sea, from the banks of the river and from Île aux Coudres, located a little downstream from the site of the sinking. The wreck posed a danger to navigation so it was subsequently dynamited and moved to a trench dug on the bottom of the river to provide the necessary clearance for the passage of deep draft ships.

The Tritonica only received its first visitors in 2016, aside from the hard-hat divers involved at the time in the post-sinking work. Despite the very limited visibility, exploring the wreck allowed our team to note the absence of its central superstructure, a section removed because it was too high and close to the surface.

A duty to remember

Exploring the remains of ships involved in such disasters is particularly exhilarating.

But alongside these tons of rusty steel that fascinate divers so much, there are often human tragedies. We must never forget this.

The privilege of visiting the relics of our past and bringing their stories to the surface must always be carried out with great respect.

Sébastien Pelletier received funding from the IHQEDS (Institut Environnement, Développement et Société) of Laval University.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.