When Dominic Perrottet admitted to wearing a Nazi uniform to his 21st birthday party, he apologised to Jews and veterans – but not to the other groups who were persecuted by the Nazis, including disabled people.

However, disabled people were the first victims of the Holocaust. They were murdered in a number of Nazi programs specifically targeting them, as well as those that targeted Jews, Sinti, and Roma.

In 2023, International Holocaust Remembrance Day marks 90 years since the Nazis assumed power, and immediately began their persecution of everyone they thought of as “inferior”.

The Nazis frequently described disabled people as “useless eaters”, “empty human shells”, and “life unworthy of life”. They chose these labels to evoke images of people who were incapable of doing anything, and so needed to be kept in institutions for their entire lives, wasting the tax dollars of non-disabled people.

A suite of policies implemented by the Nazis forced disabled people out of German society and into institutions, where they worked until they were murdered.

Most disabled people lived in the community

In early 20th-century Germany, most disabled people lived in the community. In the mid-1920s, a national government survey of disabled people (the only one conducted during that era) found that few disabled people lived in institutions permanently. In fact, only a minority of disabled people lived in institutions at all – and this was often for education or rehabilitation, when they were young.

For example, though 17.5% of blind people lived in “schools for the blind”, the majority (80.4%) of blind people were adults living in the community. And a third of those disabled people with the highest rates of institutionalisation – the psychologically or intellectually impaired – lived in the community.

A network of organisations managed by and for disabled people prioritised gaining and maintaining employment. Some, such as the German Association of Blind Academics, established in 1916, focused on a particular profession. Others, such as the Self-help League of the Physically Handicapped, established in 1919, created training and jobs for its members. In 1929, it had a membership of 6,000 throughout Germany, and was a role model for a similar organisation in Austria.

This trajectory of increasing self-determination and community involvement of disabled people ended when the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Read more: Three charts on: disability discrimination in the workplace

Exclusion and government hate campaigns

One of the first legislative changes that affected all disabled people, as it did all Jews, was their exclusion from the new marriage loans program, which lent money to each newly married couple, and forgave a quarter of the loan for each child they had.

Given Germany’s economic instability and high rates of unemployment, this financial assistance was significant – but only marriages “in the interest of the national community” were eligible. Both Jewish and disabled people were also ineligible later that year, when farms were made available to people who would not otherwise have an inheritance.

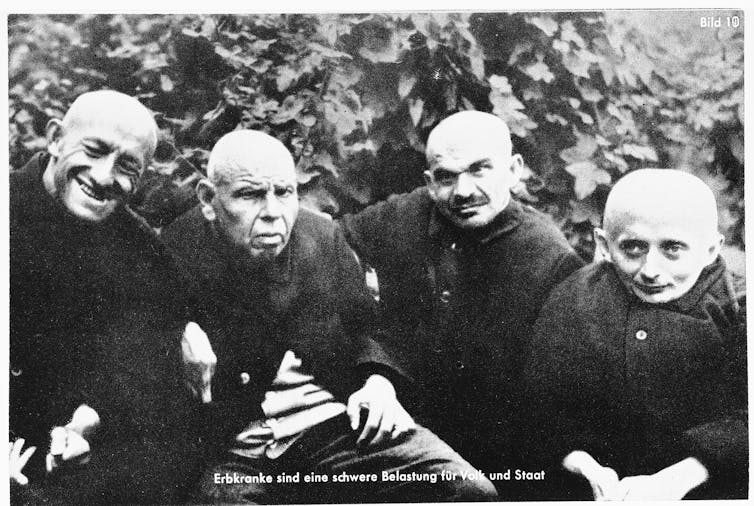

These laws were accompanied by a relentless government hate campaign. In schools, libraries, and waiting rooms, there was a succession of posters, pamphlets, and magazines, reminding “Aryans” of their superiority, and of the undesirability of everyone else.

Tours through institutions where disabled people were forced into scenes of helplessness became commonplace. These tours were mandatory for anyone who was planning to marry, in order to dissuade the couple from proceeding if there was any chance their child might be “unfit”.

In this atmosphere, the Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases, which made the sterilisation of disabled people compulsory, encountered little opposition when it was enacted on 14 July 1933.

When it officially took effect, on 1 January 1934, movies and travelling exhibitions were added to the hate campaign. These stifled any remaining opposition, and made it impossible for the victims of this law to maintain any privacy about their personal circumstances.

Those who objected to their sterilisation were labelled unpatriotic. Those who did not object to their sterilisation were labelled inferior. And either way, women who were sterilised were then targeted for rape. Foreshadowing the Nazis’ increasing incarceration of disabled people, the only way to avoid sterilisation was to commit oneself to an institution.

It became increasingly dangerous for disabled people to be seen in public, let alone to work. To force them into institutions, it was now only necessary for the Nazis to target the few remaining avenues they had for remaining in the community – marriage and education.

In 1935, one month after sexual contact and marriage was prohibited between “Aryans” and Jews, it was also prohibited between “Aryans” and disabled people. In the same year, disabled people were not permitted to attend school past elementary level. And within two years, they were not permitted to attend school at all unless it was part of an institution.

Aktion T4 and the murder of disabled people

The Aktion T4 program targeted disabled adults in Germany and Austria, murdering them in gas chambers attached to institutions. Though it is the most well-known of the programs that specifically targeted disabled people, it was not the first, and not the only one.

The murder of disabled children began on July 25 1939, and was soon part of the procedure of designated hospitals throughout Germany and Austria. In September, the Nazis began murdering the patients in the asylums of the countries they occupied, beginning with Poland.

The first victims of Aktion T4 were murdered in October – the program had a quota of 70,000 victims. When this quota was reached, most of Aktion T4’s staff were assigned to establish the “final solution”, and the euthanasia of disabled people was transferred to hospitals.

Disabled people were victims of every other Nazi extermination program, too. Whether they had found a way to remain in the community, or became impaired due to Nazi violence or the work they were forced to do, many disabled people were incarcerated in concentration camps and ghettos. 3,200 blind people were deported from Theresienstadt alone.

These events are important to remember – not only as history, but as an example of how short the path from exclusion to murder can be.

Amanda Tink does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.