Paris pools have symbolised athleticism in the French capital dating back to the 1924 Olympics – a century ago. The French fondness for swimming may not surpass the national penchant for cycling, football, tennis and rugby – even in this Olympic year that celebrates all sports. But architecturally speaking, its passion for the pool continues strong – and speaks volumes.

For the 1924 event, the city commissioned the big, brutalist architecture-style Piscine des Tourelles (later renamed Piscine Georges-Vallerey) in the deepest reaches of the Télégraphe neighbourhood. Its success as a crucial infrastructure project for working-class Paris inspired other iconic pools like the art deco Molitor, now part of a luxury hotel, and Espace Pontoise, which just emerged from its own restoration.

Paris pools: a passion for swimming

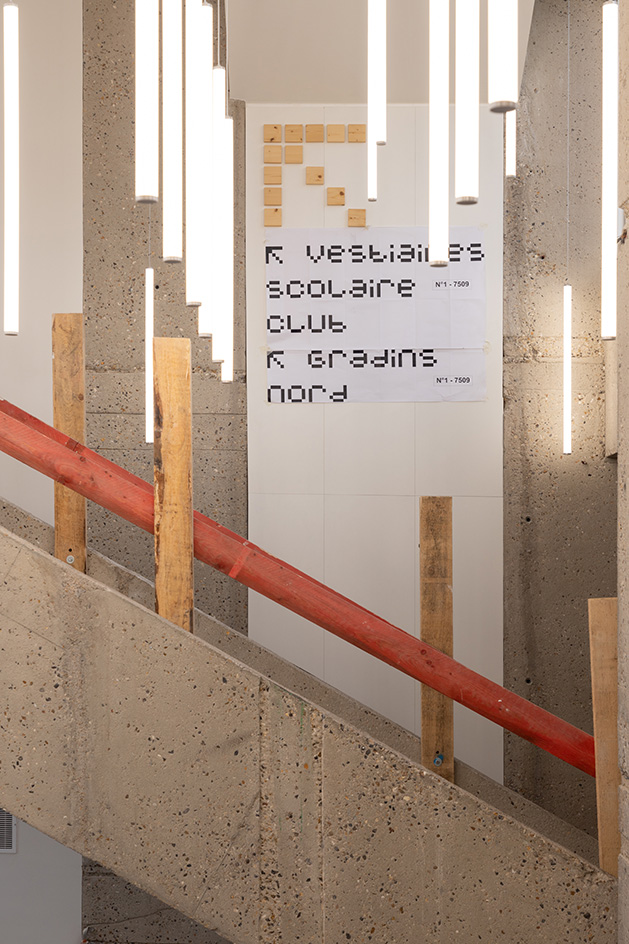

Regular renovations have brought Georges-Vallerey’s 50m pool up to date, with a retractable roof and water heaters. Yet its selection as a training venue for the 2024 Games presented an opportunity to truly modernise the venue. Romain Viault of AIA Life Designers headed up the project, using materials donated by a local recycling scheme. Limited quantities of new Douglas pine, required for the sun-ray roof framework, came from sustainable forests in Jura and Vosges. Meanwhile, larch, recouped from the original roof, was used towards new furniture and signage.

In a similar spirit, organisers of Paris 2024 commissioned environmental champions VenhoevenCS to design the Centre Aquatique (Aquatics Centre), the only new permanent venue sanctioned for this year’s Games (a building as yet to be unveiled). Working with local practice 2/3/4 and Schlaich Bergermann Partner as structural engineers, Venhoeven tailored the building to less sprawling events like artistic swimming, diving and water polo. Yet, like Georges-Vallerey, it’s become a showcase for sustainable wood construction, with the hopes of future athletes embedded in its every beam.

The facility occupies a postindustrial site in historically deprived Saint-Denis, next to the Stade de France, the pillar of this year’s Games. To link the two venues within a larger master plan, the architects built an 18m-wide pedestrian bridge over the impeding N1 motorway and landscaped huge swathes of brownfield around it.

The pool is defined by its 89m suspended glulam roof, built from ribbons of construction-site waste. Doubling as a massive solar farm, it will produce enough electric power for 200 households. And yet the concave shape dips low enough that heating and cooling requirements will be minimal. The wider footprint will adapt to community needs but always remain transparent, encased in glass with a slatted-timber frame.

Beyond the Games, hopes are that the public will flow in and out freely, not only to swim but for any number of pursuits in the common spaces. But the real hope is for the next hundred years – that if Paris were to host again, these two pools would suit just fine.