If an anatomical description of the clitoris only appeared in some French school text books as recently as 2017, that’s because the seat of female pleasure, known by this name since at least 1559, was deeply taboo for so long.

Through history, anything pertaining to female arousal has often been erased, or regarded as dangerous or obscene – and Antiquity was no exception on this front.

In the TV series Rome(2005-7), legioniary Titus Pullo gives some advice to centurian Lucius Vorenus, who wants to give pleasure to his wife Niobe.

“Tell her she looks beautiful, all the time, even when she doesn’t,” Pullo says.

“Anything else?” Vorenus asks.

“Yes,” says Pullo. “When you make love to her, touch the button between her thighs and she’ll open up like a flower”

“How do you know Niobe has this button?” asks Vorenus.

“Every woman has one”.

The scene parodies The Art of Love, the erotic masterpiece by Roman poet Ovid which is set out as a seduction guide. In the first part, the author offers his tips to men who want to conquer a woman – sweet affectionate gestures, kisses, tender words, compliments… By these means, a suitor can make himself agreeable to a woman and bring her pleasure.

The poet doesn’t mention the clitoris in this work. Perhaps he alludes to it, nevertheless, when he writes: “Shame stops a woman from bringing on certain caresses: but it’s delicious for her to receive them when someone else takes the initiative” (The Art of Love, Book I, 705-706).

Nymphs and clitorises – ancient medics’ views

Even if Ovid doesn’t specifically feature it, the clitoris is very present in Greek and Latin medical literature. Soranos of Ephesus, author of Gynaikeia, a book about women’s health from the 2nd century AD, sets out a description of women’s sex organs.

He calls the clitoris ‘numphé’, or nymph – a word that denotes either an unmarried girl or a married young woman. This isn’t out of decorousness however: it relates the clitoris, which would normally be hidden by surrounding flesh, to the young female face. “If one calls this part the nymph”, the writer explains, “it’s because it hides under the lips, like young girls hide under their veil”.

The Greek word ‘kleitoris’ is used by Rufus of Ephesus, a contemporary of Soranos, author of anatomy book The Name of Body Parts. Without doubt linked to the verb ‘kleio’ (‘I shut’) the term also conjures the idea of an invisible organ, held prisoner within a confined space.

If the ‘nymph’ isn’t sufficiently demure but more or less protrudes, Soranos considers, that’s an anomaly needing surgical correction. The doctor advises slicing it off with a scalpel, taking care of avoiding too heavy a bleed.

This operation was performed at that time in Egypt, as the geographer Strabo describes (Geography, Book XVII, 2, 5). The author doesn’t name the clitoris but speaks of a form of female circumcision, conveyed by the Greek verb ‘ektemnein’ (‘removing by cutting’).

Obscene mosaics

In Latin, ‘numphé’ is translated as ‘landica’, a term one finds in the Latin version of a Soranos of Ephesus treatise by 5th century AD Roman doctor Caelius Aurelianus. Etymologically, the word might hint at the idea of a ‘little gland’ (‘glandicula’ in Latin).

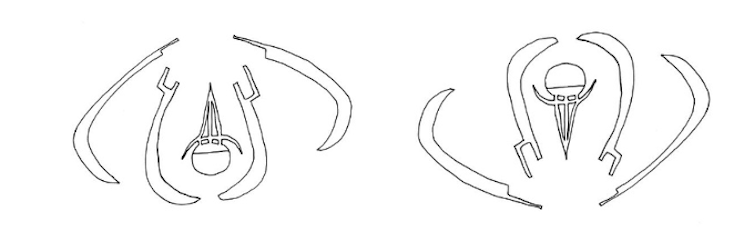

A mosaic in the opulent House of Menander in Pompei offers us an artistic rendering. It adorns the entrance to the Caldarium – the dedicated area for hot baths. One sees four cleaning implements, bronze scrapers, arranged around a vial of oil which is hanging from straps. These were objects routinely used by the Greeks and Romans in their sporting activities.

The bather walking into the room probably wouldn’t have been surprised by the subject matter, although the composition of the objects might strike him as a bit curious. It’s only when you leave the room that the artist’s undoubted intention becomes clear. Seen from the other direction, the image evokes a vulva. Around the clitoris, represented by the vial of oil, the scrapers take the form of labia.

In the upper part of the mosaic, a young African servant is running, holding two phallic vases, while his big penis bursts from his tight loincloth. It’s certainly a way to get a laugh out of onlookers with the juxtaposition of this comically virile image with the suggestion of the female organ, made up of items of men’s sports equipment.

Pig with a prickle

In contrast to the phallus – a veritable lucky charm with all kinds of beneficial properties in the thinking of the time - the clitoris was seen as a potential danger to men.

On the House of Menander mosaic, the vial of oil, seen from one side, takes on the appearance of a sharp weapon – a kind of dagger. It chimes with the definition of the clitoris given by Greek poet of the 1st century AD Nicarchus, a writer of satiric epigrams. Casting scorn on a certain Demonax, skilled at cunnilingus, Nicarchus wrote, “The pig (‘khoiros’) has a fearsome prickle (‘akantha’)”.

“Pig” is a slang term for the vulva, while “prickle” refers to the clitoris, seen as a miniature penis spelling danger to men’s lips. Demonax, licker-out of vaginas, runs serious risk of hurting and bloodying his mouth.

A myth of female dominance

In the Odyssey (Book X, 389) Circe the enchantress has a little sceptre called a “rhabdos”, ancestor of the sorcerer’s magic wand.

The object doesn’t represent Circe’s clitoris but it is does symbolise a magician’s powers. Circe seduces men – she lures them to her palace where she makes them lose their humanity, transforming them into pigs. She makes them submit, in a symbolic manner, to the power of her “pig”, her vulva, making them slaves to it.

Happily for Ancient Greek patriarchy, Odysseus ends up by conquering and bringing to submission Circe’s vulva. He possesses it, using his phallus, and defuses the wielder of the magic wand, symbol of harmfulness.

Today, in a 180 degree shift away from those negative classical world representations, artists are celebrating clitoral power. The organ has become a symbol of the vindication of women’s rights – for example in the sculpture, jewellery and other work by Brooklyn-based Sophia Wallace for her Cliteracy project

This article was translated from French by Joshua Neicho.

Christian-Georges Schwentzel ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.