Dick Biondi, a broadcasting dynamo whose 67-year career spanned the history of rock ’n’ roll in America and defined Top 40 radio for a generation, never lost his youthful enthusiasm for the music, his buoyant delivery on the air or his boundless affection for his fans.

The golden oldie disc jockey known as “The Wild I-Tralian” died June 26, according to an announcement by his family. He was 90.

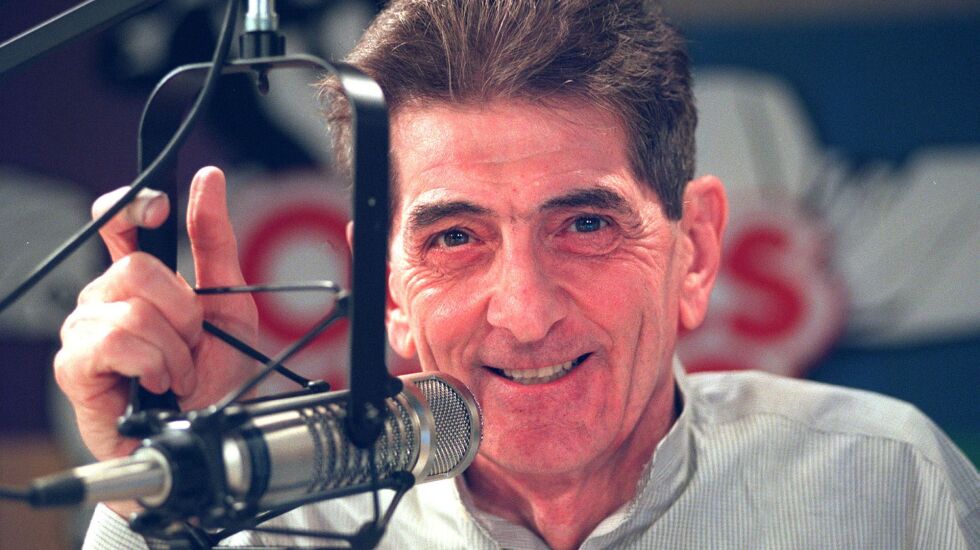

Biondi, who claimed to have been fired from 25 radio stations over his lifetime, never wanted to retire and rarely took vacations. Until he was sidelined with health issues in April 2017, he had been a fixture at classic hits WLS 94.7-FM since 2006.

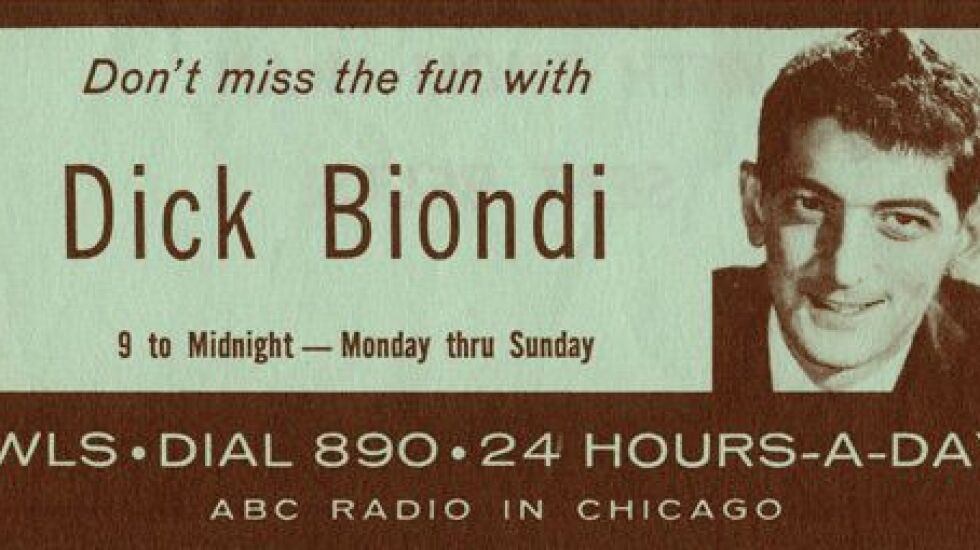

At his peak as nighttime personality on Top 40 powerhouse WLS 890-AM from 1960 to 1963, Biondi commanded an unheard-of 60 percent share of all listeners, attracting millions of adoring teens in 38 states and Canada. During that time, he was twice voted the No. 1 disc jockey in America by Billboard magazine.

Influential in advancing the careers of Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly and Jerry Lee Lewis, among many others, Biondi was the first disc jockey to play the Beatles on American radio, debuting “Please Please Me” in February 1963. He emceed the Beatles and Rolling Stones in concert.

“Dick Biondi helped introduce rock ’n’ roll to a generation of kids, including me,” C-SPAN founder Brian Lamb said in his induction of Biondi to the Radio Hall of Fame in 1998. “He was loud, fast talking, full of platter chatter and crazy stunts,” said Lamb, who grew up listening to him in Lafayette, Indiana.

The late radio consultant Mike “Hot Hits” Joseph once called Biondi the single best DJ in rock radio history. “He sounds and sounded like a rock jock should,” Joseph said.

What was the secret to his longevity in the business? “I have never lost the drive and the desire,” Biondi told me. “Radio is the greatest way of communicating in the world. Nobody, nobody can get more intimate than your voice getting into somebody’s head.”

Born September 13, 1932, in Endicott, New York, Richard Orlando Biondi made his radio debut at age 8. It happened courtesy of Bob Morgan, an announcer at WMBO in Auburn, New York, where Biondi’s grandparents lived. “I was standing outside his studio watching him, and he called me in and told me to read a commercial for Brotan’s, a women’s clothing store in Auburn,” Biondi said. From that moment on, he was hooked.

With the encouragement of his parents, Biondi pursued his interest in radio during high school, working behind the scenes at WINR in Binghamton, New York. He fetched hamburgers and coffee for Rod Serling, later of “Twilight Zone” fame, and was tutored in pronunciation and diction by sportscaster Bob Cullings. “He taught me to say ‘the’ instead of ‘duh’ and ‘three’ instead of ‘tree,’ ” Biondi recalled. “I got to work with a lot of wonderful guys there who gave this little Italian kid a chance to get into the greatest business in the world, and that’s radio.”

In 1950, two weeks out of high school, Biondi landed his first on-air gig at WCBA in Corning, New York, as a sportscaster. His budding career hurtled him to Louisiana, Pennsylvania and Ohio before returning him to Upstate New York, where he became known as “The Big Noise from Buffalo” at WEBR.

Two weeks after he was fired there, Biondi got a call from Sam Holman, program director of WLS, inviting him to help launch a new rock ’n’ roll format, “The Bright New Sound,” on the 50,000-watt former Prairie Farmer station.

On May 2, 1960, Biondi signed on as the 9 p.m.-to-midnight personality at WLS. Yelling his way to the top (one of his other nicknames was “The Screamer”), he quickly became a superstar. Fans loved his fast-paced, high-decibel delivery, his crazy antics on and off the air, and his hit novelty record, “On Top of a Pizza,” an off-key parody of “On Top of Old Smoky.” His personal appearances at high schools and clubs (known as “record hops”) became mob scenes.

Exactly three years to day after he started, it abruptly ended when Biondi left WLS in a dispute with management over the commercial load on his show. An urban legend persisted for years that Biondi was fired for telling a dirty joke on the air, but the truth was far less risqué.

After four years in Los Angeles, where he worked at KRLA and hosted a nationally syndicated show, Biondi returned to Chicago in 1967 at WCFL, then a competitor to WLS. He later spent a short time at WMAQ before leaving Chicago again in 1972 and embarking on another multi-city radio odyssey.

Biondi’s career had stalled in North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, when Bob Sirott came calling in 1982. A former Chicago DJ whose career had been influenced by Biondi, Sirott was working as a feature reporter for CBS-owned WBBM-Channel 2 and tracked down Biondi for a “Where Are They Now” profile. Response to the interview was so impressive that Top 40 WBBM 96.3-FM brought Biondi in for a fill-in stint and wound up hiring him as morning host.

Though the WBBM job lasted less than a year, Biondi was back in Chicago for good. By 1984 he was hired to launch the oldies format at WJMK 104.3-FM “Magic 104,” where he spent the next 21 years. A format change there sent him back to his old station and call letters, WLS — this time on the FM side — in 2006. He moved from late nights to Saturday and Sunday mornings in 2015.

For more than 20 years, Biondi hosted an annual marathon remote broadcast from area shopping malls — keeping him on the air for as long as 36 hours nonstop — to collect toys and cash donations for needy children at Christmas.

In addition to the Radio Hall of Fame, he was enshrined in the radio exhibit of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Illinois Broadcasters Association Hall of Fame. In 2010 the city of Chicago celebrated the 50th anniversary of his start on the air here by naming the alley south of the old WLS studios near East Lake Street and Garland Court “Dick Biondi Way.”

“What’s it feel like onstage? You walk out there, you’re nervous, you’re shaking. And I always wondered: ‘Do I really belong out here?’ ” Biondi told Chicago filmmaker Pamela Pulice, a lifelong fan who produced a documentary about Biondi’s career. “When you think back to when you were 8 years old reading a commercial in Auburn, New York, and here you are standing before thousands of people, it is a high that no drug, it is a high that no romance will ever give you.”

He is survived by his wife Maribeth, and sister Geraldine Wallace.

A private family interment has been held.

Robert Feder is a retired Chicago media critic and former TV/Radio columnist for the Sun-Times.