Steve Braunias on the visit of a genius 100 years ago today

DH Lawrence arrived in New Zealand 100 years ago on this day, a genius ablaze with his red beard and his blue eyes and his head filled not so much with thought as a constant white heat, sailing into Wellington on a passenger ship bound from Sydney. He was 36 years old, an Englishman in a woollen suit and tie. He was gaunt, sickly. He arrived in bad weather. He travelled the world in search of warm climates – Sicily, Sardinia, New Mexico; Ceylon was a bit too hot, so he went to Australia. The Tahiti entered Wellington harbour at 6:10am, and berthed at Queen's Wharf at 9:15am. Winds strong to gale force with heavy rain: the little wooden houses on the dark hills circling the harbour in the shabby little colony at the end the world: it immediately presented as a loathsome sight to one of literature's most fluent haters. Lawrence and New Zealand got off to a bad start on Tuesday, August 15, 1922. It was to get worse.

No one knew he had come to town. The press would have been all over him. He was the famous and opinionated writer of novels such as Sons and Lovers (1913), The Rainbow (1915), and Women In Love (1920) – the orthodox view is that his best work was behind him by the time he arrived in Wellington, with John Middleton Murry declaring he was one of those novelists who “appear to have passed their prime long before reaching it.” The art of fiction wasn't enough for Lawrence. He was a prophet with a Very Important Message. That was a shame. Lawrence was never at a loss for a bad idea. TS Eliot means this as a compliment: "Lawrence has an incapacity for what we ordinarily call thinking." He had utopian ideals, was counterculture before it became an organising beatnik principle. He wanted to form a cult built around himself: "We are going to found an Order of the Knights of Rananim.”

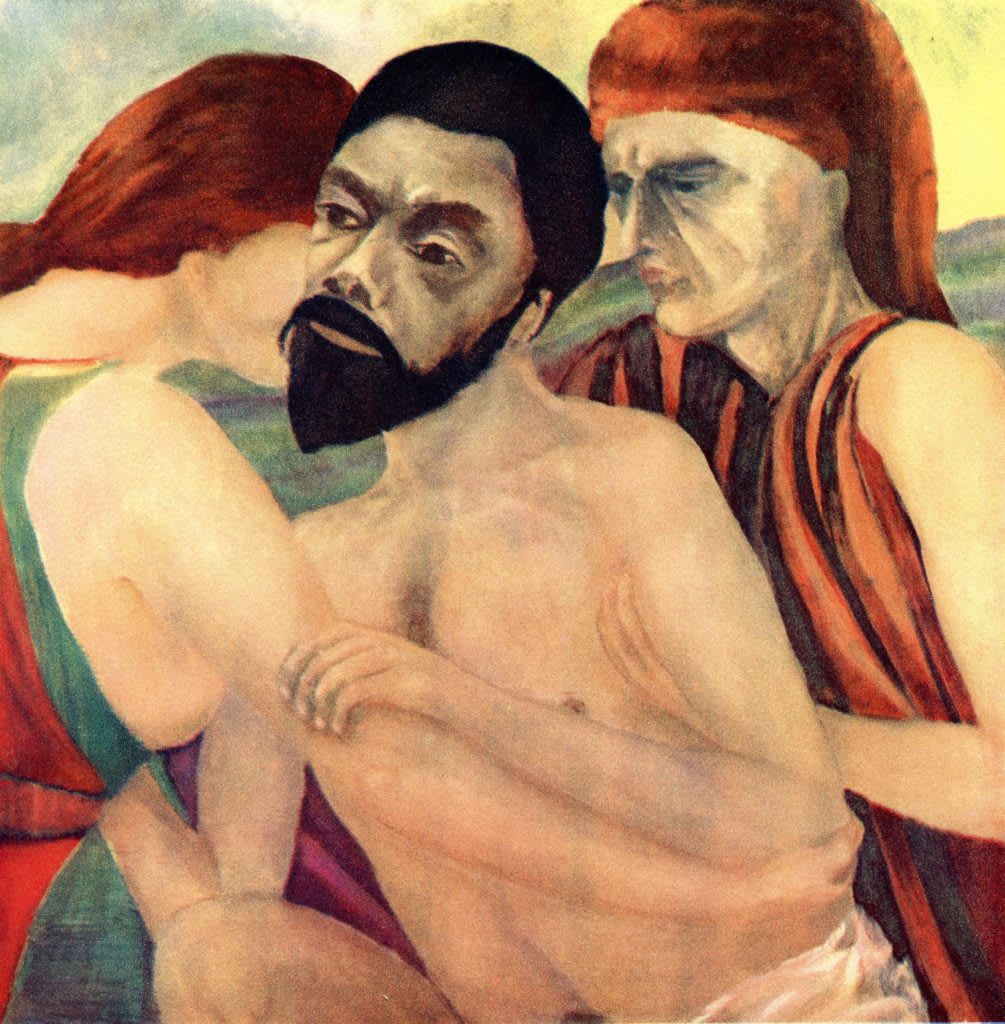

Lawrence, the great author; Lawrence, the holy fool; Lawrence, at roam in the world. He was on his way to New Zealand from Australia, where he had lived for 99 days, renting a brick house in the sandy streets of Thirroul, on the coast near Wollongong in New South Wales. He was only ever busy, a maniac forever doing things with his hands, like scrubbing floors, stitching clothes, milking cows, building chairs, painting doors, painting self-portraits of a staring Messiah – and writing, forever writing, completing most of his novel Kangaroo in Thirroul, then tinkering with different endings after his time in Wellington. New Zealand had got into his writing. He wasn't sure what to do with it. He didn't know what to make of Australia, either, hated the people ("so crude in their feelings") and their shallow belief in the joys of capitalism, but the last chapter of Kangaroo is a fond farewell: "This place—it goes into my marrow, and makes me feel drunk. I love Australia." He especially adored the golden wattle in bloom, "all gold, great gold bushes full of spring fire rising over your head." The novel's wandering hero is Lawrence under another name (Richard Somers). With some regret, Somers boards his passenger ship at Circular Quay. The gangway is hoisted, the ship's hooter hoots its goodbyes. "He felt a deep pang in his heart, leaving Australia, that strange country that a man might love so hopelessly." The ship passes through the Heads. The last sentence in the finished version of Kangaroo reads, "It was only four days to New Zealand, over a cold, dark, inhospitable sea."

I asked Ohakune-born author Martin Edmond, now living in Sydney, if he'd ever visited Thirroul. He replied, "Yeah I've been there a few times. It's a narrow coast down that way, caught between the escarpment and the sea, and I've always found it a bit claustrophobic. Might even have stood in front of Wyewurk, gawking." He meant the name of the red-brick holiday cottage that Lawrence rented in Thirroul. Lawrence described it in Kangaroo: "A little front all of grass, with loose hedges on either side - and the sea, the great Pacific right there and rolling in huge white thunderous rollers not forty yards away." Strange to think of Lawrence wandering the sandy streets. In an interview published at the excellent Australian site Inside Story, Thirroul's barber later described him thus: "The most morose-looking fellow you ever met.” It chimed with the reception Lawrence got at a Bloomsbury party in 1915, when Lytton Strachey described him thus: "I've rarely seen anyone so pathetic, miserable, ill, and obviously described by internal distresses." Well, yeah, but another way of putting it is that Lawrence hated every second of getting to know the Bloomsbury set. He was working-class, a sullen outsider among ruling class chatterboxes. They made him feel, he said, "mad with misery and hostility and rage".

He hated their empty talk. His manly ideal was Mellors the gamekeeper in Lady Chatterley's Lover, who danced naked in the rain, ecstatic in the physical world that so fascinated and animated Lawrence. Thirroul's barber commented, “I don’t think that he really came to have his beard trimmed but to ask questions.” Lawrence asked about rock formations, about trees, about ferns. If his novels are a mess of terrible ideas (and essays, too; his classic "Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine" starts off as a compelling record of nature raw in tooth and quill, then becomes an intolerable racist tract), his nature poems remain unequivocally wonderful pieces of writing. His famous poem "Snake" records his observation of a snake drinking from a water trough in Sicily. So maybe all the poem's snakey assonances are too obvious. So that's Lawrence for you, untrained, non-U, literature's raving savage.

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

He read that there were 32 species of golden wattle in Australia, and he identified seven. At Thirroul, there were more than 300 bird species, as well as the tree frog, the pygmy possum, the she-oak skink. Nature gave him something so rarely associated with Lawrence: happiness. The happiest pages of Kangaroo are set in the bush.

But there were deeper, darker pleasures going on beneath the surface of the novel, or at least according to Sue Rabbitt Roff, who sounds credible – she writes on cultural aspects of settler colonial Australia, has held positions at Monash University. Beware academics, journalists and various other assorted parasites of genius who begin sentences, "It's as if..." Roff claims of Lawrence, "It’s as if three months spent in Australia has allowed, perhaps forced, him to contemplate his own inclinations and to resolve them into the celebration of heterosexual sodomy that is central to his last novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover."

What? Lawrence, the writer of a stupendous range of work, including novels, short stories, poetry, essays, travel writing, and not entirely but very often cheerless letters (a message to a friend in 1919 begins with a cough of rage: "faugh! - humanity - I can't bear to be mixed up with it"); Lawrence, who could do it all as an author; Lawrence, only ever good for sodomy. Many writers are narrowed down to one single thing about their work or lives and for Lawrence it was the joy of anal. University paper, 2012: "Anal Sex: D.H. Lawrence and the Back Door to Transcendence". But nothing of the sort actually happens in Kangaroo, and only once, celebratively (Roff is right about that), in Lady Chatterley. Mellors and Constance are in his love shack in the woods. Lawrence writes, "It was a night of sensual passion, in which she was a little startled, and almost unwilling: yet pierced again with piercing thrills of sensuality, different, sharper, more terrible than the thrills of tenderness, but, at the moment, more desirable. Though a little frightened, she let him have his way, and the reckless, shameless sensuality shook her to her foundations, stripped her to the very last, and made a different woman of her…It was sensuality sharp and searing as fire, burning the soul to tinder. Burning out the shames, the deepest, oldest shames, in the most secret places. It cost her an effort to let him have his way and his will of her. She had to be a passive, consenting thing, like a slave, a physical slave. Yet the passion licked round her, consuming, and when the sensual flame of it pressed through her bowels and breast, she really thought she was dying: yet a poignant, marvelous death. "

The "secret places"! Germaine Greer despises the novel, and writes of Constance, "Connie just lies there, apparently hallucinating." So much of that book – so much of what Lawrence wrote, and he wrote a lot – is so crazy. His attitudes towards women ("she let him have his way") make him impossible to forgive, and, even more damagingly to his lasting reputation, according to Lawrence scholars Geoff Dyer and Florence Wilson, his novels are so impossible to read, so windy and boring. Wilson and Dyer both argue for the riches in his other work – some essays, some poems, some letters. That's why they bother with him in the first place; that's the point, these pages of singular and towering genius. Wilson wrote a biography of Lawrence last year. Dyer edited a selection of his essays. He joked of his publishers in an interview with Vanity Fair, "They’ve made so many attempts to revive Lawrence’s fortunes and nothing seems to work. This is the final chance, this is the final application of those paddles to his chest."

The patient has not yet revived. His legend burned out long ago. The best the present can give him is a charming little cottage industry - there's a DH Lawrence Birthplace Museum in his home town of Eastwood (the cafe serves cream tea and scones), and the 15th DH Lawrence International Conference was recently held in New Mexico (includes free shuttle from Albuquerque). Lawrence belongs to the past, or to two pasts – the two occasions he achieved any success was once in his own lifetime, with Lady Chatterley's Lover, his last novel, which finally made him rich, and he also remains fixed in 1960, 30 years after his death, with the massive publicity of an Old Bailey trial which lifted the ban on Lady Chatterley. It made him a household name; it made him sexy. It inspired Philip Larkin's lines about sexual intercourse only becoming widely available "Between the end of the Chatterley ban/ And the Beatles' first LP."

Please Please Me, and Constance Chatterley; the English at play, in bed, liberated – there is a cruel metaphor in the novel, where Connie's husband Clifford, paralysed from the waist down from injuries he received fighting in the trenches of World War I, gets his wheelchair stuck in the mud. Lawrence, the liberator; Lawrence, the phallic god ("So big!" gasps Connie. "So proud! And so lordly!"); Lawrence, only one half of the entire equation of sex and his earnest search for "phallic tenderness between man and woman". The thing about anal is that you can't do it by yourself. Lawrence is not alone as the Tahiti is tied up at Wellington wharf in the wind and rain. He stands on the deck next to his long-suffering, long-loving wife, who sacrificed everything for him, who went into exile with him, who was the model for Constance Chatterley, who never wavered in her conviction that she was married to a genius: Frieda.

*

Frieda Weekley was married and the mother of three children when she met Lawrence. He was 27 and she was 34. It was madness at first sight. In all the unseemly romances in the history of literature - Eloise and Abelard; Sylvia and Ted (Hughes was crazy about Lawrence's poetry); Maurice Shadbolt and half the women in New Zealand - Lawrence and Frieda were among the strangest and strongest romances.

She was from German aristocracy, Lawrence raised in a working-class family in the Midlands. (His father worked the coalmines and was more or less illiterate. Anthony Burgess hosted a South Bank Show portrait of Lawrence in 1985, and spoke with people living in Eastwood, the small mining village where Lawrence was raised; they declared, "The father was worth 10 of the son." You knew where you were with the father: under the ground, tapping at coal. You never knew what the son was thinking, especially when he tried to explain himself.) Lawrence attended Nottingham University. One day in 1912 he arranged to call on Professor Arthur Weekley, a philologist and the author of Adjectives and Other Words. Years later, still in Nottingham, known far and wide as one of literature's most famous cuckolds, Weekley was invited to tea with a visiting celebrity, Eminent Victorians author Lytton Strachey, who dismissed him as "a pompous old ape". Weekley was Frieda's pompous old husband until Lawrence showed up at his door. The rest was hysteria.

We have this account of their behaviour in a letter written in May 1916. "Let me tell you what happened on Friday. I went across to them for tea. Frieda said Shelley's Ode to a Skylark was false. Lawrence said: 'You are showing off; you don't know anything about it.' Then she began. 'Now I have had enough. Out of my house - you little God Almighty you. I've had enough of you. Are you going to keep your mouth shut or aren't you.' Said Lawrence: 'I'll give you a dab on the cheek to quiet you, you dirty hussy. ' Etc. Etc. So I left the house. At dinner time Frieda appeared. 'I have finally done with him. It is all over for ever. '

"She then went out of the kitchen & began to walk round and round the house in the dark. Suddenly Lawrence appeared and made a kind of horrible blind rush at her and they began to scream and scuffle. He beat her - he beat her to death - her head and face and breast and pulled out her hair...Finally they dashed into the kitchen and round and round the table. I shall never forget how Lawrence looked. He was so white - almost green and he just hit - thumped the big soft woman.

"Then he fell into one chair and she into another. No one said a word. A silence fell except for Frieda's sobs and sniffs. In a way I felt almost glad that the tension between them was over for ever - and that they had made an end of the 'intimacy'. Lawrence sat staring at the floor, biting his nails. Frieda sobbed. Suddenly, after a long time - about quarter of an hour - Lawrence looked up and asked...a question about French literature...Then Frieda poured herself out some coffee. Then she and Lawrence glided into talk, began to discuss some 'very rich but very good macaroni cheese.'

"And next day, whipped himself, and far more thoroughly than he had ever beaten Frieda, he was running about taking her up her breakfast to her bed and trimming her a hat."

Twenty years ago the word for this kind of relationship was dysfunctional. The word for it now is toxic. When it happened, there was less of a desire for brisk one-word summaries of complex human behaviour – the Lawrence's were dysfunctional, they were toxic, they loved each other until the day Lawrence died in 1930, aged 44. Frieda mixed his ashes into the cement floor of a shrine she built to Lawrence. She then got on with her life, writing to one of her lovers (Lawrence the cuckolder was serially cuckolded): "I am waiting for you." In a tidy parallel to her own desertion of her family, the man abandoned his wife and three children for her. They lived noisily ever after. Tennessee Williams came to visit in 1939, and wrote, "The picnic at Frieda’s was a tremendous experience. At first, I heard a huge, bellowing laugh from the basement—then the floor begins to quake—then she APPEARS!...You should see her. Still magnificent. A valkyrie. She runs and plunges about the ranch like a female bull—thick yellow hair flying, piercing blue eyes—huge. She dresses madly—a hat & coat of bob-cat fur."

It’s a portrait of boisterousness, someone outsized and blowsy - a Blanche DeBois screeching in a German accent. Frieda is so often remembered this way, and worse. In his South Bank Show programme, Anthony Burgess stares at the screen with his eyes set deep in his magnificent head, and intones how Lawrence did all the work around the house while she lay back in bed, "smoking, and getting fatter and fatter". He meant at their house in Taos, New Mexico, where they moved to after their ship left Wellington. But a contemporary account from Taos records her "cooking huge meals, baking bread and cakes in the outdoor Indian oven, and making butter in a little glass churn". Similarly, her desertion of her three children to live with Lawrence is viewed as cold, ruthless, but it's not true. She later wrote, "The price I had to pay was almost more than I could afford with all my strength. To lose those children, those children that I had given my life to, it was a wrench that tore me to bits." As an adulterer, Frieda was denied custody or even access to her children under existing English law. A friend was asked to bring the kids to her in secrecy. Lawrence arranged it in a letter: "You will help, won't you? Then Frieda might meet them at your house."

She suffered. She loved, fiercely and often. She was marvelous fun ("a huge, bellowing laugh"). These are the unofficial but actual versions; the preferred version is coarse, and always, eventually, concerned with sodomy. "Richard Aldington [a friend of the Lawrence's] tells us that Frieda Lawrence was an anal sex enthusiast." Does he? Says who? The claim is made by our old friend Sue Rabbitt Roff, for whom sodomy was so apparently central to Mr and Mrs Lawrence.

Perhaps it was, probably it was, but the thing about anal is that it can be really quite time-consuming and there are only so many hours in the day. You can narrow a reputation down to a single event, or to a governing desire or a serious crisis, but life as it's lived is a catalogue of so many other things to get on with, to get done, to get. Let us inspect the activities of Mr and Mrs Lawrence on their four-day crossing from Sydney to Wellington. The authority on Lawrence in New Zealand, and the voyage on the Tahiti, is Patrick Waddington. He is the author of a splendid paper published by the DH Lawrence Society. Lawrence is only one of his subjects – Waddington is an Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature at Victoria University – but he dives deep and detailed into the events of 1922, and has brought back this vital piece of information about life onboard the Tahiti in that four-day crossing: Frieda beat other passengers at a game of whist.

The Lawrence's travelled first-class. There were 127 passengers. Waddington supplies the list of New Zealanders onboard: Mr and Mrs FA King (say it out loud, lol), L Lister, HV Prentice, Mrs C Clabburn, and others with old, stiff, Anglo surnames, although the passenger list also includes J Wairoa. There is no escape on a ship; Lawrence wrote, "It was hateful never to be able to get away from Australians, New Zealanders, American, French."

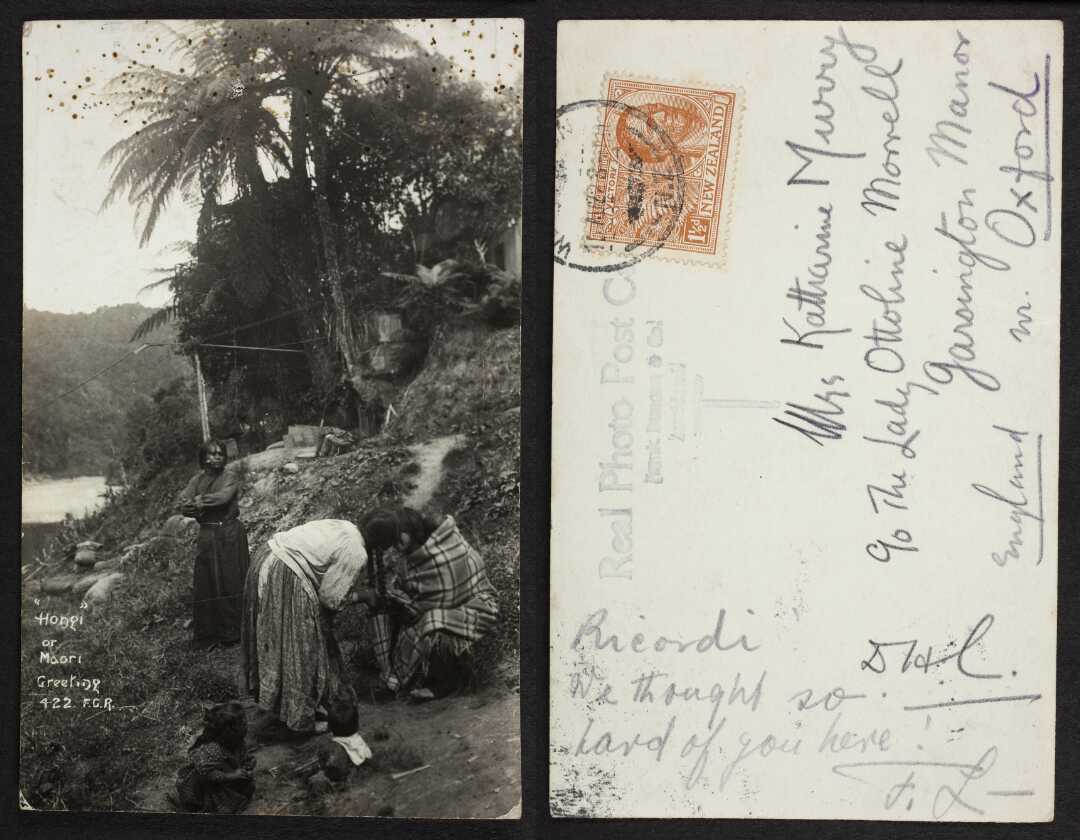

The Tahiti was due to depart Wellington at three in the afternoon. Enough time, Waddington speculates, for the Lawrence's to walk downtown, and look at exhibits in the art gallery, or buy a ticket at a cinema to watch The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse starring Rudolf Valentino. But the only evidence that Lawrence was ever even in New Zealand was that he bought and posted four postcards.

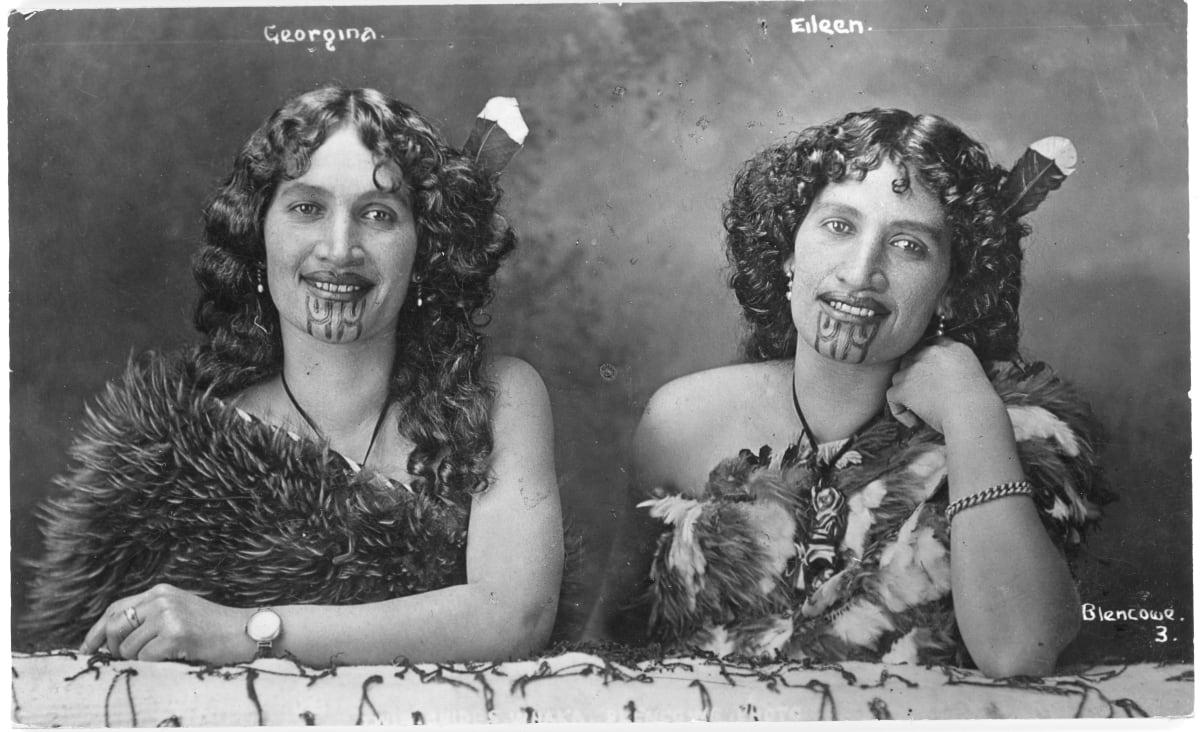

He went for the kinds of pictures every other tourist went for. He chose a postcard of Milford Sounds to post to his sister Ada. Two other cards were of Māori guides at the Whakarewarewa thermal wonderland in Rotorua. Lawrence sent one to his sister of Guide Pipi (Te Aranai Haerehuka, painted by Goldie) alongside Guide Eileen (Eileen Te Rauoriwa, twin sister of another guide, Georgina Te Rauoriwa), and posted a card of Guide Emma (Emma Hikurangi) to a friend. A copy of the fourth postcard has never surfaced (* see update at end of story) but it contained a poignant and beautiful message to the only living soul he knew from New Zealand, who grew up in the city where his ship had berthed, who was the author of that 1916 account of the shocking fight between Lawrence and Frieda ("thumped the big soft woman"), who was the dear and trusted friend that Lawrence beseeched to stage an elaborate ploy so that Frieda could set eyes on her children ("You will help, won't you?"), who was very much on his mind on this day 100 years ago when he experienced a typically awful winter's day in Wellington: Katherine.

*

Katherine Mansfield and her husband John Middleton Murry first met the Lawrence's in June 1913. Frieda wrote in her autobiography, "We had tea with Katherine at her flat in London. If I remember rightly her room had only cushions and pouffes and a large aquarium with goldfish and shells and plants. I thought her so exquisite and complete, with her firm brown hair, delicate skin, and brown eyes which we later called her 'gu gu' eyes. She was a perfect friend and tried her best to help me with the children. She went to see them, talked to them, and took them letters from me. I loved her like a younger sister."

What a lovely portrait. They were so close that when Mansfield and Murry went to the Lawrence's wedding, Frieda gave Katherine her ring from her first marriage, and she wore it to the day she died. The two couples holidayed together, and tried to live together as part of Lawrence's idea that they all form a commune. It didn't work out. They had good intentions. They all set to painting chairs and polishing brass, and Mansfield wrote a letter that began admiringly: "He [Lawrence] has become very fond of sewing, especially hemming…When he is doing these things he is quiet and gentle and kind." The problem was when he was not doing those things. "He simply raves, roars, beats the table, abuses everybody…After one of these attacks he's ill with fever, haggard and broken." Mansfield and Murry made their excuses, and got the hell out. Lawrence to Murry: "You're an obscene bug." Lawrence to Mansfield: "I loathe you...You revolt me…I hope you will die."

They lost touch - gee, really – and they never saw each other again. Lawrence was at once charismatic and repulsive. It's as if (!) he couldn't stand to be with people but knew they were kind of necessary to form a cult. He drove the Murry's away, made it impossible to endure his rages (Mansfield: "He is completely out of control, swallowed up in an acute, insane irritation.") Their genius had so little in common – Mansfield, fine and exact; Lawrence, boundless and epic ("I could ride," he once enthused, "after Atilla the Hun, with a raw beefsteak for my saddle") – but it had been a deep friendship. Mansfield was loyal and true. Once, when she overheard customers at the Cafe Royal deriding a collection of his poems, she went up to them and snatched the book away.

Towards the end of her life she intended to write to Lawrence and suggest they all meet again in England. It was too late. She wasn't going anywhere. She was sick. They both had TB and it killed them both. Mansfield died on January 9, 1923. She had made out her will a year earlier, leaving a book to each of her friends; Lawrence was on that list. Poignantly, the very same day she wrote her will – August 14, 1922 - Lawrence was on the other side of the world, his ship 24 hours from arriving in the city of her birth. Thoughts of her filled Lawrence's mind at the exact same time thoughts of Lawrence filled her mind: Katherine Mansfield writing her will at the Château Belle Vue in France: DH Lawrence heading for New Zealand. He got to Wellington the next day and bought her a postcard. He thought of all their times together, his friendship with that watchful New Zealander with the gu-gu eyes, their experiments at communal living, their shared past, and he put it all down in one word, in the only word that he scrawled on the back of the postcard, that reached her in London in September: "Ricordi." Translation, "reminisce."

He sent the card across the sea, and looked around him. Wellington, beaten with frantic winds, the harbour grey and dismal, rain dripping, dripping, dripping on the dark hills – it was a port in a storm, a greedy colonial outpost, designed for nothing more uplifting than trade and empire. Lawrence describes his character of Somers in Kangaroo: "He was a man with an income of four hundred a year, and a writer of poems and essays. In Europe, he had made up his mind that everything was done for, played out, finished, and he must go to a new country. The newest country: young Australia!" What about New Zealand? Wasn't that even newer, even younger? He stood on the deck of the Tahiti, seething. If a newspaperman had been tipped off that a famous author was in town, he would have approached Lawrence with inky hands and asked, "What do you think of New Zealand?" Lawrence put the question to himself, and it nagged at him as he worked on the ending of Kangaroo. The final version read, "It was only four days to New Zealand, over a cold, dark, inhospitable sea."

But there were other, earlier versions. The indispensable Patrick Waddington records them in his masterly paper on Lawrence in New Zealand. Kangaroo was going to end with Richard Somers and his German wife Harriet (as Frieda) having to deal with a classic Wellington species: some petty little civil service fuckwit.

Lawrence wrote, "At Wellington a great fuss filling in papers for the Immigration Authorities, even though the boat was staying only a day. And another insult from a fat individual who came aboard as chief official. He looked at Harriet's form, saw she was not born in England - or the Empire - and did not give her a landing card.

"Richard was livid with rage at the fellow's insolence. They waited until the whole gang was through, and he was prepared to have it out with the person. But, having kept them hanging about for an hour, the person was satisfied with himself. He handed Harriet her landing card, saying suavely: 'You are going on by this boat, Mrs. Somers?' 'I am. I've no desire to stay in New Zealand.'

"You land in a great port – Naples, Colombo, Sydney, San Francisco – and you find perfect simplicity and courtesy. But in would-be Wellington, a nobody in a uniform.

"Ah well, it lies away in nowhere, behind the great sea: the great void Pacific, where the heart seems to die, and the Pacific Isle rise golden, sunny, but cruelly at the heart of nowhere, as if one could not breathe.

"After a day in Wellington, cold and stormy, they had less desire than ever to stay in this cold, snobbish, lower middle-class colony of pretentious nobodies."

The ship was due to leave at 3pm. It was late getting away, at 4:40pm. It rained. The afternoon sky had darkened. There was nothing to see, anyway. Lawrence had had enough of New Zealand, that damp isle of nothing. He sat in his cabin, and continued writing. With acknowledgements to Patrick Waddington's wonderful piece of literary detective work in his paper on DH Lawrence in Wellington.

* UPDATE, 6:20pm: I was quite wrong to declare that Lawrence's postcard sent to Katherine Mansfield 100 years ago today "has never surfaced". The card is reproduced below.

My thanks to Cherie Jacobson, director of the Katherine Mansfield House and Garden in Wellington, for emailing this afternoon to state that the card is actually in possession of the Turnbull Library. It was included among six boxes of Mansfield papers gifted to the library by the family of John Middleton Murry in 2012. I was wrong, too, to think that it only contained the single word, "Ricordi", or "memories". That was thought to be the case ever since Mansfield wrote to Murry to say, "‘I had a card from Lawrence today – just the one word ‘Ricordi’. How like him. I was glad to get it though." But there is one other message, even sweeter and more emphatic, scrawled on the back of the card: "We thought so hard of you here." Lawrence and Frieda signed the card. It may be that both messages were written by Frieda, with her husband merely signing the card – it’s hard to tell, but the thickness of his signature certainly differs from the thinner script of her signature and the message.

As for the image, it shows a hongi between two Māori women on the banks of a river. There's no available information on who they were – there never was of Māori in settler postcards; they were positioned as exotic props – but it's possible the setting is the Hātea River in Whangarei, a favoured setting of the man who photographed the postcard, Frederick Radcliffe. "A slight, moustached, courteous and kindly gentleman," as described by the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Radcliffe came out from England in the 1890s, and settled in Whangarei. He established a thriving postcard business. "Radcliffe recorded pictorial images of rural and urban New Zealand from the far north to Bluff on nearly 8,000 glass-plate negatives." He died on January 14, 1923, just five days after the death of the recipient of his hongi postcard, Katherine Mansfield.