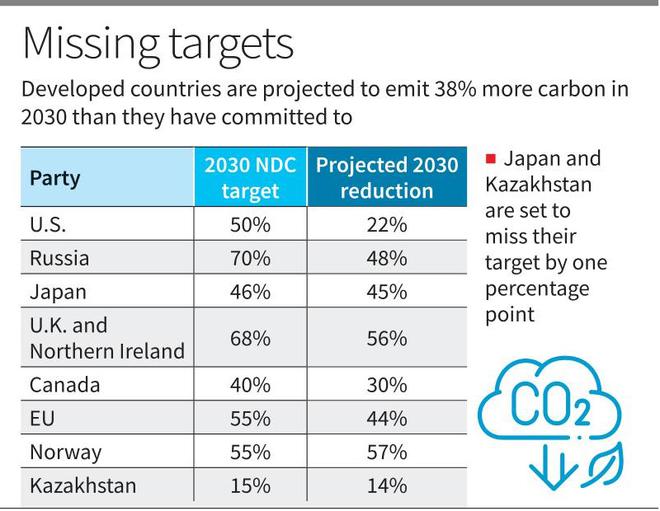

In the run-up to a key global climate summit, an analysis shows that developed countries — responsible for three-fourths of existing carbon emissions in the atmosphere — will end up emitting 38% more carbon in 2030 than they have committed to, going by current trajectories, In fact, 83% of this overshoot will be caused by the United States, Russia, and the European Union, according to a study published last week by the Council for Energy Environment and Water (CEEW), a Delhi-based thinktank.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change will hold its 28th Conference of Parties (COP-28) at Dubai in November and December. Countries are expected to give an account of their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are their commitments to the UN on emission cuts.

Falling short

The CEEW study noted that the NDCs of developed countries already fall short of the global average reduction of emissions to 43% below 2019 levels that is needed to keep temperatures from rising above 1.5°C. Instead, developed countries’ collective NDCs only amount to a 36% cut.

For a fighting chance at keeping warming below critical tipping points, decades of negotiations have obliged developed countries to lead global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions with legally binding targets. Collectively, developed countries were to reduce emissions by 5% from their 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012, and by 18% per cent during 2013 to 2020.

While these countries ostensibly kept their promise and cut emissions by 20%, it was not the result of any “planned exercise”; in fact, a significant chunk of the cuts were the result of the COVID-19 pandemic that caused a global economic slowdown, the CEEW researchers said.

Postponing needed cuts

Several countries have committed to achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Doing so would require steady measurable cuts every decade until that year. As an intermediate objective, countries presented data to the UN on their projected cuts until 2030. To keep temperatures below 1.5°C, developed countries need to cut emissions to 43% below their 2019 level. However, the CEEW study found that, based on their current emissions trajectories, their cuts would likely amount to only 11% by 2030. Except for two countries — Belarus and Norway — none of the developed countries seem to be on the path to meet their 2030 targets, though Japan and Kazakhastan are close, and are expected to miss their targets by only a single percentage point.

Most developed countries appear to be planning to achieve their 2050 net zero targets by taking on deep emission cuts only after 2030; which, going by their own track record, seems over-ambitious. For instance, were all developed countries to reach net zero by 2050, they would require more than four times the average annual reductions they achieved between 1990 and 2020.

Shifting the burden

“The climate journey of developed countries — historical and proposed — does not show deep enough emission reductions to reflect climate leadership. This means that the burden to mitigate global warming shifts to developing countries, which is problematic in a context where financial support to developing countries to achieve this transition has not been forthcoming, as promised,” said CEEW programme lead Sumit Prasad, one of the authors of the study. “Instead of relying on future events, developed countries should define clear year-on-year reduction plans to meet their targets in this critical decade. Further, to build trust, developed countries need to be reliable and stay committed to the Paris Agreement,” the study’s authors aver.

One of the major sticking points in global climate negotiations is the extent and speed with which individual countries must transition away from the use of fossil fuels. Developing countries say that developed countries, who are responsible for most of the carbon burden, must pay developing countries for transitioning and wean themselves away faster. Developed countries argue that countries such as India and China, given their size, cannot entirely absolve themselves from steeper emission cuts. Developing countries have also not received much of the billions of dollars promised by developed countries to aid renewable-energy infrastructure.