View the original article to see embedded media.

There are five guys comprising the top tier of this year’s quarterback class, and more than that who have been the subject of draft chatter the last few months. They’re aware of what the world thinks. They know.

There’s no Andrew Luck this year. There’s no Trevor Lawrence. There’s no Joe Burrow, Kyler Murray or Matthew Stafford. There might not even be a Mac Jones.

“We all hear it,” North Carolina quarterback Sam Howell said over the phone, late Saturday morning, less than two weeks ahead of draft day. “I don’t really take it personally. People are going to say what they believe, and that’s what they get paid to do. Whether they’re right or wrong, it doesn’t really matter. I can speak for myself, I truly could care less what anyone says about me. They try to judge all these draft guys before the draft every single year, and then they go in the league and they’re either going to play well or they’re not.

“And they’re going to guess, and 50% of the time they’re going to be right, and 50% they’re probably going to be wrong.”

Howell’s right on two counts.

One, whether his half-and-half estimation is accurate, he’s correct to say that, five years from now, there’ll be some predraft prognostications that look prophetic and others that look like they fit for someone’s parody Twitter account. History tells us that.

Two, the five we referenced—Howell, Liberty’s Malik Willis, Pitt’s Kenny Pickett, Ole Miss’s Matt Corral and Cincinnati’s Desmond Ridder—are going to have the opportunity Howell was talking about to show everyone they were wrong about the class. They’ll have it in large part because all five should go inside the top-100 picks, and top-100 picks generally gets plenty of chances to prove themselves.

And that’s why I thought it’d be good this week for all of you to get to know a couple of the quarterbacks in that mix, hear their stories, and assess for yourselves who they are and where they might go next. Later in the week, we’ll have a more detailed assessment of the five from coaches and scouts, with the good, the bad and the ugly of the group. For now, we’re going to introduce you to Howell and Ridder.

Those two, as I see it, are symbolic of the class—good, solid kids and teammates, and ultraproductive college players who have flaws in their profiles that teams have had to get comfortable with over the last couple of months.

I think you’ll like their stories.

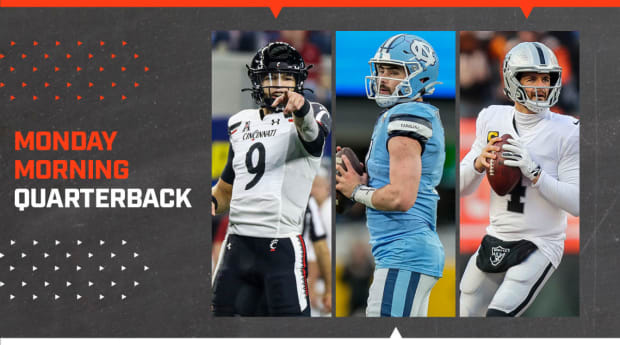

Cara Owsley/The Enquirer/USA TODAY Network (Desmond Ridder); Jim Dedmon/USA TODAY Sports (Sam Howell); Katie Stratman/USA TODAY Sports (Derek Carr)

We’ve got 10 days to go until the first day of the draft, and lots to touch on in the column. In this week’s MMQB, you’ll get …

• Josh McDaniels on the Derek Carr contract and its symbolism.

• Why timing matters in the Kyler Murray tumult.

• How the sixth pick could affect Jimmy Garoppolo and Baker Mayfield.

• A bunch of draft buzz.

And a whole lot more. But we’re starting with the quarterback class and, fittingly, the stories will begin in a pretty humble place.

Cara Owsley/The Enquirer/USA TODAY Network

Metaphorically speaking, there’s something fantastic about a turning point in the path for one of these guys happening in a port-a-potty at not the Kentucky Derby but the Kentucky Oaks, the race held in Louisville the day before the big one, six years ago.

And it’s 100% factually, too—Ridder got his Cincinnati offer, from then Bearcats coach (and now U.S. senator) Tommy Tuberville in a portable toilet on the Churchill Downs infield.

Ridder was a high school junior. He’d done the summer circuit the year before, going to the Elite 11 and Rivals camps. He starred for Louisville power St. Xavier that fall, at the time more as a runner than a passer (while listed at 6'3½" and 178 pounds), before breaking his foot early on in basketball season, which created just enough doubt that coaches wanted to get a second look once he got healthy.

So Cincinnati receivers coach Blake Rolan went to Louisville to see Ridder throw, and a week later he asked Ridder to work out again, with Rollins bringing offensive coordinator (and now Bengals coach) Zac Taylor along with him for the return engagement. Taylor went back impressed enough with Ridder’s arm, athleticism and leadership, which was evident even in that short interaction, to try to sell Tuberville on offering him.

Which led to a big moment in Ridder’s life coming at a less-than-opportune time.

“In Louisville, every high school on that Friday, on Oaks, gets off, and basically all the high schoolers go to Churchill Downs and have a good time there,” he said. “And I was in the middle of that and it was loud and crazy, so the closest spot that might’ve been quiet was a port-a-potty. So I went in there, because coach Tuberville was calling me, and sending out the offer.”

At the time, Ridder’s only other offer was from Eastern Kentucky. Days later, he accepted his second, and what would be his final, offer from Tuberville.

Tuberville stepped down six months later and was replaced by Ohio State defensive coordinator Luke Fickell, who had no idea what he was inheriting. Five years later, he says, it’s easy talking to NFL teams about Ridder, because, “There are so many good things you can talk about.” But at the beginning? There were smaller signs. Fickell remembers Ridder, the true freshman, getting hurt in camp and coming back to challenge, in the coach’s words, “a bunch of guys who thought they were Alphas” as the scout team quarterback.

By Week 6 or 7 of that year, Fickell says he and his coaches were privately saying, “Holy s---, we should probably just put this kid in the game.” The next year, with senior Hayden Moore back for his third year as starter, he and his staff decided to give Ridder the third and fourth series of the opener against UCLA. And as Fickell says, “Des went in and never came out for four years. Scored on his first series, took us down the field, and it was just like, holy cow, I don’t know exactly what, but he’s got it.”

From there, Ridder made the staff look genius and—this is the key to Fickell, as to how Ridder translates to the NFL—gave his team something a little different every year, as he grew and the team’s needs changed.

“His freshman year we didn’t have very good wideouts, and he didn’t throw the ball very well and he won us 11 games. I mean, just someway, somehow,” Fickell said. “And then his sophomore year, we started to become a little bit better, and he got dumped onto his head and shoulder by Chase Young in the second game of the season against Ohio State, played with a separated shoulder for about four or five weeks, so we really didn’t throw the ball very well. And he found a way to win 11 games for us.

“Junior year, we had a whole new receiver core just starting to come on, COVID, he had a rough start to the season throwing the ball, some picks. And he won all but one game again. And then his senior year, they said he didn’t have accuracy, so he went all summer, worked his ass off and he won us 13 games last year. Every year he won us games different ways.”

By the end of it, Cincinnati became the first Group of 5 team to make the College Football Playoff, with Ridder’s final game coming against mighty Alabama.

But it was the lead-up to that final, magical season that’d probably interest NFL teams most, as to where Ridder might take his game next. And that really started with a meeting last December. Ridder was considering going to the NFL (he’d been told he’d be a late Day 2 or early Day 3 pick), his girlfriend, Claire, was six months pregnant with their daughter, Leighton, and Fickell went in knowing the score.

“I’ve been fortunate enough to have a lot of those conversations over 25 years,” Fickell said. “Being at Ohio State, a lot of guys leave early. They were your position guys, and 90% of the time, you sit at that meeting, and this is what they’re gonna do and they’ve already made up their mind.”

Then, the meeting happened, and where hangers-on usually get involved, the audience the coach had was striking, as was the tone of the meeting.

“He brought his whole family,” Fickell said. “And we sat and talked for three hours. He hadn’t made up his mind, and we talked for three hours. ... I was shocked, because, you’re right, having a baby, getting married, all those things; if he’d come in and said, I’m gone, I’d have said, I understand.”

Instead, Ridder was focused on where he could get better, and the legacy he wanted to leave behind at Cincinnati. He also thought the stability of keeping Claire where she was, close to family, and staying in the environment he was in, trumped the benefits that a few more bucks might bring, particularly with the chance of NIL legislation passing in the months to follow. So he left the meeting and put a plan on paper, with input from Claire, Fickell, his offensive coaches, and his mom, Sarah Ridder, and stepdad, Aaron Ice.

He’d stay at Cincinnati, and he’d get better as a result

First, he got his own quarterback coach, Jordan Palmer, and made weeklong trips to Southern California in February and July to work with the trainer (who works with, among others, Josh Allen and Joe Burrow), while having year-round, weekly sessions with him via Zoom. Ridder started playing ball as a linebacker and center, didn’t switch to quarterback until middle school and had never had a private tutor—making him a sort of counterpoint to today’s classically trained passers who have their own coaches in grade school.

“It just opened my eyes,” Ridder said. “I just went out there and worked, and brought it back to Cincinnati and just continued to work it—and now I’ll always work it.”

Specifically, Palmer taught Ridder to relax his shoulders in throwing the ball, keeping his feet balanced, getting his hips going on throws to his left and playing from a stable position in the pocket. And the work paid off on his first throw of the year. On the second play from scrimmage in the opener against Miami of Ohio, Ridder took a shotgun snap, deftly moved to his left to avoid pressure and unleashed a bomb to Tyler Scott for an 81-yard score.

“It was a post route,” Ridder said. “Just being in the pocket with a little pressure, but still balanced, still stable in the pocket, good rotation through the hips. I knew that it had all paid off at that point.”

The other piece of the puzzle was how Ridder was empowered within the program to, as a three-year captain, take another step forward as a leader.

On Sundays, after a light practice, he’d meet with coaches and give input into game-planning for the next week. On Mondays, the players’ day off, he’d first lead a players-only quarterbacks meeting to review the last week’s game and introduce the others to the game plan for the week, then do another such meeting with the linemen, then another with the receivers. And on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays, he, the line, the backs and the tight ends would meet after dinner to watch tape and review communication at the line.

“Really understanding and breaking down how the tackle and the tight end work together to get up to the mike [linebacker], or maybe where the running back fits off the guard, little things like that, how the center communicates with his guards on different run plays, just learning the ins and outs of that,” he said. “I don’t think that does anything but help your game.”

And all of it not only set the stage for Ridder to take another step, yet again give Fickell and his staff something new (for a fourth straight year) and push the Bearcats to a level that no team outside the Power 5 conferences had ever reached. It also, in his mind, prepared him for the next decade of his life.

As he saw, even if he wasn’t in the NFL, he was operating like it, and now it should be easy for him to continue operating that way, arriving in the league a year later than he could have. Part of that, of course, is to keep drilling the stuff he has for five years, and building off of what he learned the last 12 months—and that means continuing to look at himself critically, the same way he did when he decided to return to school.

In meetings with teams, in fact, I’m told he’s compared himself to Titans QB Ryan Tannehill, which, of course, is different from someone calling himself the next Brady. It’s with a purpose, too. He knows he’s like any player. He needs work (he says the “accuracy thing” is one area he’s focusing on, as is pocket efficiency). But if the last year taught him anything, it’s that work can get him where he wants to be, as a franchise quarterback in the NFL.

“I’m very confident,” he said. “Once I set my mind to something, I’m gonna get it done. And that’s something I want to do, that’s obviously a life goal of mine, and I’m just excited to be able to get to where I’m going and be able to put in that work, get to know new guys, get to learn a whole bunch of new football and then ultimately, at the end of the day, go win a Super Bowl.”

So he sees big things ahead, just as he’s left big things behind him, so much so that Fickell struggles to put his impact into words.

“I don’t know that you can,” he said. “I mean, there’s been a lot of other guys that helped us set and create the atmosphere and culture and things like that. But nobody has meant more and done more, and it’s not just because of winning. It’s the way in which he’s won. It’s the way in which he’s led. To be a humble leader, to be a leader by example, with all the other things that have been thrown at him, I mean, every year he’s done new things.”

And in 10 or 11 days, we’ll see who’s betting on that to continue.

Jim Dedmon/USA TODAY Sports

Howell wasn’t overlooked like Ridder was. A top-100 national recruit, the North Carolina native had offers from Alabama, Clemson, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Ohio State and Oregon, among others, and at one point was verbally committed to Florida State. And yet, at the wire, on signing day, he chose to take a path analogous to Ridder’s, flipping from the Seminoles to UNC to take on the challenge of leading Mack Brown’s ground-up build.

“It is home,” Howell said. “For me, I just wanted to play early. And I thought that North Carolina, they had a really good team, and they just needed a quarterback to go in there and run the show. I saw that opportunity with coach Brown coming back, I had a lot of confidence in him, and I had a lot of confidence in the guys that were already there that I could go in there and just get the skill players the ball and do my best to turn that program around. For me, I just saw an opportunity there.”

Safe to say he took it—he won the job right away, the Tar Heels’ win total jumped by five with Howell starting as a true freshman in 2019, and UNC improved again, to 8–4, in ’20.

Then came the real test, which changed what the Heels needed from their quarterback. And, Howell would argue, prepared him for what he’s now getting ready to do.

UNC lost running backs Javonte Williams and Michael Carter, and receivers Dyami Brown and Dazz Newsome to the NFL after the 2020 season (all four were drafted), and it didn’t take long for the coaches to recognize that they had a bit of a problem on their hands. A season-opening loss to Virginia Tech only drove the point home for everyone, that the program was in transition, and in an all-hands-on-deck spot to generate offense.

“Honestly, going into the season, me running the ball wasn’t a plan. We didn’t plan on me running the ball any more than I did the previous year,” Howell said. “We planned on running our same offense, the same system that our coordinator, Phil Longo, does a really good job with, the same system he’s been running for years. … And we were struggling a little bit, and we couldn’t really find an identity. And we just started trying new things.

“Me running the ball was just something that we had success with. So they came to me and asked if I was fine if it became a bigger part of the offense.”

Howell, who says he’d routinely log 15 to 20 carries in games in high school, told the coaches he’d do whatever he needed to do to win. So the coaches, more or less, put a saddle on his back. Howell logged at least 11 carries in all 12 of UNC’s games, he averaged more than 15 carries per game, and he had 17, 18, 21, 17 and 18 carries in the Heels’ last five regular-season games.

“It’s a little bit different, just relying on my legs a little bit more,” Howell said. “The previous year, I really didn’t. So progression-wise, instead of going through all four progressions, sometimes, I’d go through, maybe stop after my third look, then try to run and get what I could get. It was a little different. I would say the biggest difference is probably just from a physical standpoint and a recovery standpoint, just trying to take care of my body. Luckily, I stayed pretty healthy all year long, and I’m thankful for all the people who helped me.”

Now, context is important here, too. Howell came into the year, one without a Lawrence on the landscape, as one of a few quarterbacks with a shot to break through and assert himself as the best one in a flawed class. So it’d have been easy for him to look at the plan laid out by Brown and Longo as one that would stunt his development, as a passer with a reputation for having outstanding vision and being a good distributor.

Instead, Howell looked more inward, and at what was being asked of him as a leader.

He would still have his moments to show what he had. One was against Virginia in Week 3, during which he threw for 307 yards and five touchdowns on just 14 completions (and just 21 attempts)—“They play a true 3-3-5 defense, and they have a three-safety structure, and we had a great plan. Phil did a really good job of just scheming them up and putting our guys in really good situations. We just unloaded the clip on them.”

But even in that one, he had 112 rushing yards on 15 carries. And there were more games, like a dramatic 58–55 win over No. 9 Wake Forest, where he ran the ball 21 times, threw it 26, and quite literally was the Heels’ offense.

That said, the upshot was that, over time, Howell learned that, in a different sort of way, the experience through a disappointing 6–7 campaign actually did work to prepare him for what he’ll face in the NFL, and mostly in that every game in the pros demands a certain level of adjustment, resilience and versatility out of a player.

“I learned so much,” he said. “I just learned how to handle certain situations. I was really challenged from a leadership perspective. And I think in the NFL, you’re in a dogfight every single week. There are no cupcake games in the NFL. In college, there are some teams that are winning by 30 to 40 points every game. And you have those games that you feel pretty good about. But in the NFL, every week’s a dogfight. That’s how it was for us this past year.

“I was put in so many situations, up and down, positive and negative, just trying to stay even-keeled and just stay positive after losses. I was just put in so many different situations where I just had to come in each and every day, no matter what the outcome was on Saturday, and just be positive and bring positive energy to the team.”

And in the end, he hopes that’s what NFL teams have taken away from meeting with him over the last couple of months.

Yes, there are football elements that he believes his college path prepared him for as he goes to the NFL—namely, he mentioned Longo’s two-kill system (he’d take two play calls into the huddle and kill one to get to another against certain defensive looks, like many NFL teams do), and a progression-read element in the Heels’ offense. But it’s clear how he hopes coaches and GMs see him going into the last stages of the draft process.

“I want them to see confidence. I want them to see how confident I am in my ability to do this at the next level,” he said. “And I want them to really know how good of a leader I was at North Carolina, and how every single one of those guys on my team would fight for me. They know how good of a teammate I was. I’d do anything for my team.”

It’s fair to say his 828 rushing yards stand as a testament to that.

The stories of Willis, Pickett, and Corral are pretty compelling, too. Willis transferred away from the SEC and landed with Hugh Freeze at Liberty, where he flashed enormous upside and was put to the test in trying to elevate those around him. Pickett was a solid ACC quarterback who broke through with a Burrow-style, final-year statistical jump in an NFL system at 23 years old. Corral’s got a lot of old-school gunslinger swagger to him, that some teams will tag as cocky and others will laud as confident.

Which one will make it? I’m less sure of that than I can remember being, maybe going all the way back to 2013.

But that uncertainty will be the fun of next week, not really knowing where any of these guys are going. And just the same, it’ll be the fun of following all of them after that, too.

Joseph Maiorana/USA TODAY Sports

INSIDE DEREK CARR’S DEAL

Ask an NFL quarterback to be Tom Brady on the field, and he’ll ask where he can sign up.

Ask one to be Brady at the negotiating table, and it won’t be as easy.

But that’s the approach new Raiders coach Josh McDaniels and GM Dave Ziegler asked their quarterback, Derek Carr, to take after the two got to Las Vegas in January. And they asked Carr to do it in an environment where quarterback pay was, once again, exploding, with new deals going down for Deshaun Watson and Aaron Rodgers setting brand-new precedents at a position in which players were already paid differently than any other one on the field.

Carr, going into the final year of his deal, which was to be his ninth with the organization, was willing to discuss that from the jump. Once he saw what it would mean for him, with Vegas aggressively moving to bring in his old Fresno State teammate (and maybe the NFL’s best receiver) Davante Adams, into the fold? He was in, with both feet.

So it is that the McDaniels/Ziegler vision for Carr came together with a three-year, $121.5 million extension for the 31-year-old quarterback.

“I don’t know how [Brady’s] name came up necessarily, we may have touched on it briefly. And that’s an example—it’s kind of a unicorn, I know that—but it’s also a good example of what can happen when that player at that position chooses to do something that helps the team,” McDaniels said. “There’s not a straight line there between what Tom’s done with his situation and winning championships. But I’m sure it didn’t hurt. The reality is, it’s not a complicated conversation. The more you give to one person, the less you can give to others.

“That’s just really what it is. And so the point of that is the more we allocate to one person, the less we’re going to be able to do around that person. I think everybody saw it pretty much the same way. And look, Davante’s Davante. He probably took less, too. The goal is try to get a bunch of guys where, yes, they’re doing right by themselves, but they’re also acknowledging that if I give a little bit, then maybe our team can benefit from that.”

Here’s my take on it, and I’ve pointed this out before: It’s pretty much the exact opposite of how things started for McDaniels in Denver at quarterback in 2009. There, he and Jay Cutler instantly clashed amid speculation that McDaniels would try to trade for then Patriot Matt Cassel. Cutler was dealt before he played a game for McDaniels, and Denver would offload other “Friends of Jay” (Brandon Marshall, Tony Scheffler) in the aftermath.

In the process, it sure looked like McDaniels was trying to create a facsimile of a New England program that always seemed to suppress the personality of stars.

Conversely, in Vegas, the new guys have not only embraced and rewarded the team’s existing stars, paying both Carr and Maxx Crosby, they’ve worked to acquire new ones in Adams and Chandler Jones. So yes, it’s not only a new day in Vegas, this is also a very different McDaniels program than the one we saw last time he was in the AFC West.

With that in mind, here are three other things McDaniels and I discussed, with the news on Carr’s contract still fresh.

Part of the deal was setting an example in what this Raiders regime plans to reward. It’s no secret the respect Carr commands in the locker room—especially after how important he was as a steadying force through all the tumult of the 2021 season, one that somehow ended with the Raiders in the playoffs. And, to be sure, the Raiders are paying him because they believe in him as a quarterback, first and foremost (we’ll get to that). But showing the guys that you’ll reward those who conduct themselves like Carr and Crosby is a nice benefit.

“If you’re paying a player a rather large contract, and you’re committing to them, you’d really like for them to stand for all the things that your program is about,” McDaniels said. “And I think the two guys you just mentioned, that were there prior to us getting here, clearly they’ve demonstrated those qualities. They’re good people, they work really hard, they care about the team, they do the right things and they’re great leaders.

“To me, it’s a great situation when the people that are leading and are setting the example are also two of your best players. It comes full circle—you reward them and they continue to do the things that have earned them this opportunity. And we’re counting on them as we move forward. … It just reemphasizes what you’re looking for.”

This is affirmation of everything McDaniels has said about Carr since taking the job. And I’ve found McDaniels’s strong feelings for Carr interesting, if only because Carr hasn’t played a down for him yet, and McDaniels comes from a place where the bar for playing that position is not only high but high in a specific way. Which is why I really wanted to ask him where his confidence in his new quarterback is rooted.

“It’s no different than drafting somebody and saying you’ve watched a lot of tape, and you’ve talked to them a little bit,” he said. “You’re going out there and it’s a little bit of a leap of faith. In this case, I’d seen this guy play really well at the NFL level. So it’s not really a leap of faith here; this is founded on a lot of data, a lot of proof in NFL games. This guy’s won a lot of games; he’s done a lot of really good things at the position. I can’t speak to how he’s gonna fit in our system. I just feel like it’s a good fit.

“He’s a guy that loves football, he’s a smart guy, he’s a guy that’s had to do a lot of stuff at the line of scrimmage, he sees defenses well, he reads defenses well, he understands protections. I mean, there’s a lot of things here that I really, really like. To me, he’s a good example of somebody that you’re super excited to work with. And then he’s just demonstrated all the right characteristics and qualities since we’ve gotten hired.”

The negotiation really was smooth. From McDaniels and Ziegler to Carr and his agent, Tim Younger, there really weren’t very many bumps—with, again, the Adams acquisition greasing the skids for the real dealmaking to get going. And that was important to everyone, because of the tone it would set in a lot of different ways for all involved.

“I think that’s the way that you’d hope that they go,” McDaniels said. “I know they don’t always go that way. But Derek’s been great since we got there. All our conversations have centered around winning and trying to do the right thing for the team and put the best group out there for the Raiders that we can. And look, everybody’s got to do what’s best for themselves, I understand that. Ultimately you just hope you can come to a point where everybody thinks this is the right thing to help a team be as good as the team can be.

“That’s what happened. It didn’t take long, and a big part of that goes to Derek and Tim, and what their mindset was going into it. I think this certainly tells you where he’s at and what he wants to try to get done. It goes hand in hand with the mentality we’re trying to build.”

And so the new Raiders are off and running in the ubercompetitive AFC West.

Will it work? It’s way too early to tell. But McDaniels likes the signs, in how the team’s been able to build partnerships with its stars over the last three months, and bringing those guys in on what he and Ziegler are trying to build.

“I give these guys a tremendous amount of credit,” McDaniels said. “In today’s world, all the peer pressure, all the social media, all the rest of it, to sacrifice something for themselves for the betterment of the team, I think it speaks to the character of the men.”

With the hope being, soon enough, everyone will benefit in a very big way.

TEN TAKEAWAYS

So now the Raiders and Vikings have extended Derek Carr and Kirk Cousins, and I think it harkens back to the Chiefs’ blueprint for finding Patrick Mahomes. Those who’ve read, watched or listened to me the last few months have heard this one before. That’s because I really do think it’s smart, particularly in an era when the mandate is going to be to get past quarterbacks like Mahomes, Josh Allen, Joe Burrow, Lamar Jackson and Justin Herbert (each of whom are 26 or younger). To best illustrate it, look at where Kansas City was when it hired Andy Reid and John Dorsey. The Chiefs were 2–14, coming off a season that was both football catastrophic and real-life tragic (given the death of Jovan Belcher). They needed a reset, and Reid would give them that. But rather than gut the operation and start over, Reid and Dorsey charted a different path—taking a competent core Scott Pioli had built and working with it. The Chiefs also had the first pick that year, and for a first-year coach that often means one thing and one thing only, and that’s taking a quarterback atop the draft. Instead, Kansas City looked at the landscape, saw a lackluster group in the draft, and flipped the 34th pick and what became the 56th pick in the 2014 draft for Alex Smith. They then drafted Eric Fisher to be their left tackle. And over their first four drafts, Reid and Dorsey landed …

• Fisher and Travis Kelce in 2013.

• Dee Ford, De’Anthony Thomas, Zach Fulton and Laurent Duvernay-Tardif in 2014.

• Marcus Peters, Mitch Morse, Chris Conley and Steven Nelson in 2015.

• Chris Jones, Demarcus Robinson and Tyreek Hill in 2016.

Pioli’s core, plus Smith, made the Chiefs competitive right away (they made the playoffs in Reid’s first year), and the guys listed here kept them competitive in the years to follow. The other thing Smith did? He made it so Kansas City never had to overreach for a quarterback, because the Chiefs’ brass knew, as most smart teams do, that the worst thing a GM or coach can do is pigeonhole himself into taking one in a given year, because there simply aren’t true franchise guys in every class.

And by the time they got to 2017? They’d built the roster up to the point where, with fewer needs and a clean cap, draft capital was more expendable and they could be aggressive if they truly went head over heels for a quarterback. They did, and the rest is history—and Fisher, Kelce, Duvernay-Tardif, Hill, Morse and Conley all started on offense in Week 1 of ’18, when Mahomes officially took over as starter. So the lesson? If you’re a Raiders or Vikings fan, consider the wisdom in the patience shown in their quarterback, which led them eventually from very good to great. And if that’s not enough proof, just consider the QB group K.C. was looking at in ’13: EJ Manuel, Geno Smith, Mike Glennon and Matt Barkley.

The Carr deal doesn’t signify that the Deshaun Watson deal is an outlier, but it does put the spotlight on the next few quarterbacks—and how their negotiations will frame the lasting impact of Watson’s fully guaranteed contract. I thought NFLPA president J.C. Tretter laid it out nicely in his column on the union website this week, in which he pointed out that it was not a CBA, but individual player negotiations, that led to the standard for fully guaranteed contracts in other sports—specifically, Larry Bird in basketball and Catfish Hunter in baseball. That’s why smart agents said after Cousins signed his fully guaranteed deal in 2018, the first of its kind in the NFL, that the next few quarterback contracts would define the impact Cousins’s negotiation would have in football. Then, Matt Ryan did a more traditional structure, as did Aaron Rodgers, Jared Goff, Carson Wentz and Russell Wilson, and that was that. This time around, over the next 12 months, it’ll be Jackson, Wilson again, Joe Burrow and Justin Herbert with the bat in their hands. Will they force the issue? We’ll see. It sure sounds like Tretter was encouraging them to.

Just as last week was important for the Panthers, this week is, too. Just as the team had the quarterbacks in en masse last week, Matt Rhule, Scott Fitterer & Co. are having N.C. State tackle Ikem Ekwonu and Mississippi State tackle Charles Cross in to Charlotte together Tuesday. And I think there’s an interesting dance that’ll play out in the aftermath with the sixth pick. As I see it, the Panthers can gamble, barring someone trading up (which I think is unlikely), that they’ll have their pick of quarterbacks at No. 6. What’s hard to forecast is whether any of the top three tackles—Ekwonu, Cross or Alabama’s Evan Neal—will be on the board when Carolina’s up. If those three are gone, maybe it’ll be simplified for the Panthers and they’ll take a quarterback. But if one or more of the tackles are there, it wouldn’t stun me, or others in the league, if the Panthers grit their teeth and go with the offensive lineman over the quarterback—with perhaps the idea that they could go and get Jimmy Garoppolo after the first round, or even Baker Mayfield, who’s been seen internally as a sort of redundant gamble to what the team did with Sam Darnold last year (and would probably require the Browns’ eating a whole bunch of his $18.858 million base). Having Mayfield and Darnold, the top two quarterbacks in 2018 (both of whom were drafted before Allen and Jackson), together would be interesting, for sure. But right now, my guess is the Browns would be pushing that more than the Panthers are looking for it. Which, again, could change, depending on what happens with the sixth pick.

I don’t think Kyler Murray will be an option for the Panthers, or anyone else but the Cardinals. But the Panthers’ situation is a perfect illustration of why Murray’s camp viewed timing as so important to his situation in the first place. Carolina’s one of just a few teams left out there (Seahawks, Falcons, Lions) that don’t have their QB plans set for 2022. Once we get past the draft, you figure more, if not all, of those teams will drop off the list, because they’ll either take one or they’ll dive in on a Mayfield or a Garoppolo. And that organically takes an arrow out of Murray’s quiver, when it comes to trying to leverage a deal out of Arizona, because it’s tough to pull the trade-demand lever if there isn’t a team out there willing to give him the kind of contract he wants while also handing over a war chest of draft capital to acquire him. That’s why when Arizona told Murray and his people back in February that they’d take care of him in the summer, after the rest of the offseason business was done, that was met with strong resistance (and that strongly worded statement from agent Erik Burkhardt). So here we are now, and I’d expect Murray’s camp to try to keep the temperature high for the next couple of weeks, because there’s really no guarantee that what the Cardinals come to him with a few months from now will be what he’s looking for. And if they get there, well, given the holdout rules, Murray may have no other recourse than to play out the fourth year of his deal. Which didn’t work out really well for Mayfield, who happens to be a close friend and ex-teammate of Murray’s.

That said, there has been some benefit to waiting for Murray. It’s not unusual for a team to tell a player to wait a few months for his payday—sometimes it happens for no other reason than the owner wanting to keep the bonus money in his pocket for a few months longer (you’ll see such instances described as “cash-flow reasons” at times). But there’s downside for the owners there, too, and the Arizona situation is illustrating it, as is the spot the Ravens (who, to be fair, aren’t asking Jackson to wait now) and Jackson are in. When Burkhardt fired that first salvo, there were just three quarterbacks in the $40 million per year club. There are now seven.

• Aaron Rodgers, Packers: $50.27 million.

• Deshaun Watson, Browns: $46.00 million.

• Patrick Mahomes, Chiefs: $45.00 million.

• Josh Allen, Bills: $43.01 million.

• Derek Carr, Raiders: $40.50 million.

• Dak Prescott, Cowboys: $40.00 million.

• Matthew Stafford, Rams: $40.00 million.

So in February, a team might’ve been able to tell a player that the Allen, Mahomes and Allen deals were on a sort of super-elite tier that a guy needed a certain level of accomplishment and leverage to get to. It’s much tougher to make that argument two months later.

Kirby Lee/USA TODAY Sports

The Colts’ signing of Stephon Gilmore represents a significant trend over the last few years—and that’s smart teams signing third-contract vets. The Patriots did it constantly during their championship years, bringing in high-end players who’d come looking to gravy-train a ring. The Ravens (Mark Ingram, Calais Campbell, Eric Weddle, Alejandro Villanueva, Pernell McPhee) have turned it into an art form in recent years. And the Colts themselves haven’t been shy about taking their swings, either, with players like Xavier Rhodes, Justin Houston, Trey Burton, Andrew Sendejo, and even Matt Slauson and Mike Mitchell all back in Frank Reich’s first year in Indy. Now, the risk is obvious—maybe you’ll get a guy a year too late, and you don’t know it, or he starts to break down physically. The upside, though, is considerable, even if a guy has only a year or two left.

1) There’s a level of certainty in what you’re acquiring. A lot of times when a guy is coming off his rookie contract, you might worry about a player going into a new system for the first time as a pro. Or how he’ll respond after getting a huge payday and, in some cases, attaining set-for-life status financially. You have to worry about those things less when a guy is six, seven or eight years into his career.

2) In most cases, they’ve played for multiple coaches. This goes back to having a feel for how they’ll adjust to a new system, but is also about overall adaptability—the guy’s going to have a better chance at a smooth transition if he’s had to transition before.

3) Leadership and intangibles are part of the package. It’s fair to say that most players who last that long in the league, and continue to produce, can at the very least set an example for others on how to work and how to play.

4) You’re more likely to find a guy who was a blue-chipper and may still have some of that left in him. Indeed, plenty of the guys listed above were signed to second contracts by the teams that drafted them, because they were at a level where those teams were not going to let them hit the market.

5) Generally, the financial commitments are more reasonable, and year-to-year. Which always helps in team-building.

So I like the signing for Gilmore, for reasons we’re going to detail in a second. And I like the strategy in singing this kind of guy, too, for a team that feels like it’s close.

This move makes a ton of sense for Gilmore himself. There was a time when Gilmore was among the very best man-to-man corners in football. He showed flashes of that during what was a mostly lost half season in Carolina, and maybe he can summon it again. But he’ll be 32 in the fall and he’s been banged up, so the specifics of his next NFL home, I believe, were always going to be critical in where his career would go next. And honestly, I think he’s in as good a place as he could’ve landed. Gilmore’s length, headiness, ability to press at the line, and experience, make him, in a lot of ways, a perfect fit for the Pete Carroll–style Cover 3 that Gus Bradley’s installing in Indianapolis. When he was 27, would it have maximized him as a player? Probably not. Coaches like Rex Ryan in Buffalo and Bill Belichick in New England, schemers heavier on man coverage and disguise, were always going to get the most out of him at that point of his career. But he always had the tools to play in a system in the Carroll family. So I think this is a smart move not just because Gilmore’s getting paid fairly (the raw numbers out are $23 million over two years, and we’ll see the details of it), but because going to a place like this, where maybe he won’t be asked to be quite as freakish in coverage, could work to extend his career. Plus, with Matt Ryan on board, there’s no question Indy’s all in for the here and the now.

I had a good point raised to me this week on Jameson Williams, and why someone might take a stab at him in the first round. And it relates to a guy who played at Bama just before Williams got there in January 2021—Eagles C Landon Dickerson. “I loved Landon Dickerson coming out, but he got injured late in the year, and the doctors said he might miss the whole year this year,” said an NFC exec who didn’t get him. “And Philly got 13 starts from him. If you get 13 starts as a rookie, and a healthy player going into ’23 with Jameson, you’re cooking with gas.”

Now, it’s not a one-for-one comp. Dickerson was injured in the SEC title game on Dec. 19, 2020, and had surgery about a week later. He was activated by the Eagles on Aug. 30 and made his first start in Philly’s Week 3 game against Cowboys on Sept. 27, after seeing some action in a pinch in Week 2 against the 49ers. Williams’s ACL tear happened Jan. 10, with surgery within the week, so he’s roughly three weeks behind where Dickerson was. Which, if you follow a similar timeline, puts him potentially in position to play, or at least be activated, in late September. Now, if you’re a team that needs help right now at the position, and there are jobs on the line, maybe you wouldn’t roll the dice. But if the case of Dickerson, who had way more injury history before his last ACL surgery than Williams does, can serve as a guide, Williams’s rookie year might not be a total wash. And at any rate, all this is to say ACL injuries aren’t quite what they used to be.

I don’t know where the Kelvin Joseph case will go next, but that the Cowboys’ 2021 second-round pick is in trouble isn’t a big surprise. Going into last year’s draft, the then Kentucky corner had shown all kinds of promise—he ran a 4.34 at his pro day at 6'1" and 193 pounds, and his tape showed Pro Bowl potential. But he only landed at Kentucky after leaving LSU, a program that’s had a history of high tolerance for talented players’ off-field missteps in the past, on not-great terms (he was suspended at the end of his freshman year, then bolted). And while things may not have been as bad at Kentucky, he still had, as one AFC exec explained, “major accountability issues. … He was a lot to handle on a daily basis.” So that, at best, Joseph was hanging around with the wrong people the other night was predictable, the same way Vikings corner Jeff Gladney getting in trouble last year wasn’t really a surprise to teams that passed on him in the first round of the ’20 draft. And it’s a good thing to remember, too, when you hear a player has off-field red flags. I get that the idea of getting a first-round talent in the middle of the second round sounds like an exciting deal, and it’s worth hoping guys like this get past their problems. But it’s tough to count on it, because, as the great Patriots player (and now assistant) Troy Brown once said to me on a TV set, “Money only makes you more of what you already are.’

We’ve got our draft-centric, quick-hitting, what-I’m-hearing type takeaways here for you right now …

• It feels like everyone’s trying to trade down. There are a lot of good examples of players that make sense for teams … if only said team can trade down. Seattle and Northern Iowa OT Trevor Penning is one. Detroit and Notre Dame S Kyle Hamilton is another.

• I didn’t put Ohio State WR Garrett Wilson in my top 12 from Friday, just because I didn’t have such a match for him, but he’s one guy I’ve heard teams are a little higher on than people might realize.

• While we’re there: The biggest knock on USC’s Drake London? Speed. So, fair or not, his decision not to run the 40, after his pro day had been delayed twice, will raise eyebrows among NFL scouts. As will his “watch the tape” reasoning for it (which basically concedes it wasn’t injury- or training-related).

• Last week, I mentioned that Georgia S Lewis Cine has edged past Michigan S Daxton Hill in the eyes of some evaluators, and much of that is based on how the two are interviewing. That said, Cine’s a fun guy to talk with teams about. “The most violent guy on tape since [Johnathan] Abram,” said one exec. “This guy tries to hurt people.”

• Would the Eagles take a receiver for the third year in a row? No one’s ruling it out.

• One high-end exec whose opinion I respect said to me this week that he strongly believes Michigan DE Aidan Hutchinson and Bama’s Neal are the two safest prospects in the class. Which is one reason why, in a class full of guys with holes, I felt pretty comfortable having both in my top three in Friday’s GamePlan.

• And those two also bring to life the saving grace of a shaky top 10—maybe there isn’t a Trent Williams or Myles Garrett, but at least the guys who’ll likely go up there play premium positions like those two do.

• It was interesting hearing new Patriots director of player personnel Matt Groh say that New England is being forced away from the traditional, hulking off-ball linebacker (think Dont’a Hightower) because colleges aren’t producing them anymore. So what’s happening? Those body types are becoming tight ends and edge rushers, in a sport that’s so much more focused on the passing game.

• If there was an all-predraft-process team, I think this year’s captain might be Washington CB Trent McDuffie. He’s crushed his meetings with coaches and scouts. Add that to a 40 time in the 4.4s at the combine, and it feels like he’s comfortably positioned as the third corner in this class, behind only Cincinnati’s Sauce Gardner and LSU’s Derek Stingley Jr.

• Along those lines, every team I’ve talked to the last couple of days has mentioned Lovie Smith’s comments about the Texans needing corners to play defense the way they want to, and in particular because Smith’s Tampa 2 roots wouldn’t indicate that’d be the case. So whether it’s at No. 3 or 13 …

SIX FROM THE SIDELINE

1) I’ll have more on the USFL after the draft. My early thought: The television presentation was really nice. And that should make a difference, at least in getting people to give it a look.

2) I really love the idea of the Red Sox bringing my buddy Tony Massarotti into the broadcast booth. If anything, over the last decade or so, sports have become more about story lines and all that happens on the periphery, and less about the games themselves (especially in sports with games played as frequently as baseball). So having a talk-radio voice in there is smart, and I know Mazz is gonna kill it.

3) While we’re local, good luck to all the runners in Monday’s Boston Marathon. Just a great day in the city. I’m happy to see it back in full force, and wish I could be out there. And if you’re actually going the 26.2 miles? There’s nothing like turning that corner on Hereford and looking down the home stretch of Boylston.

4) I’m biased, but what an amazing job my alma mater did honoring Dwayne Haskins on Saturday at the spring game. Ohio State QB C.J. Stroud wore Haskins’s nameplate over the No. 7 they shared; fifth-year senior WR Kamryn Babb, one of 11 guys left on the team who played with Haskins, led a midfield prayer at halftime; and that prayer followed this video that was played in the stadium. Best to the Haskins family—hopefully there’s some solace in seeing the way all these people felt about him.

5) I watched a little bit of the Warriors the other night and officially hope they make a run, even after I wasn’t a big fan of theirs a few years back, just because I want to see Steph Curry and Klay Thompson on a bigger stage again (and the West looks like it might allow for that).

6) If you want to look for the next Jameson Williams–style breakout star at Bama, two transfers made a case for themselves in the Tide’s spring game, and they’re familiar names for college football fans. Keep an eye on Georgia Tech transfer Jahmyr Gibbs and Georgia transfer Jermaine Burton, who are vying for playing time at tailback and receiver, respectively.

BEST OF THE NFL INTERNET

They really are …

No word on the status of Firebug Jones’s season tickets (although this is probably all a good lesson for fans to calm the hell down after their team drafts a guy they don’t like).

Solid logic, and Richie would’ve been a lot of fun as a full-time head coach. Hopefully he keeps bringing the heat in his once-a-week pressers when the season starts.

Just wants to see some good games played, that’s all.

You could actually Zapruder this thing, and have like three different debates off the 12 seconds this video captures.

Fair point from Ross.

Tough look for Silk Gray. And as Kevin pointed out to me, even tougher look for JSA Authenticators.

“I’m not mad, I’m disappointed” is a powerful bullet for any coach or parent to be keeping in the chamber.

This makes me think of the time my buddy/ex-high school teammate Will Croom invited me out to play flag on a turf field about seven or eight years ago (I’d have been 34 or 35). It was a lot of fun. Then, I woke up the next morning and felt like I’d played in about three consecutive tackle games. So I don’t care that this is Fan Controlled Football. That Terrell Owens can do this in any pro arena at 48 years old is astounding.

Highly disappointing indoor basketball setup.

I think there’s actually a good discussion to be had here on offensive-line development—and how the influx of linemen from college spread offenses, added to practice rules changes in the NFL since 2011—has made it really hard for teams to build depth at those positions (since the chance for doing real applicable work is largely limited to the games for linemen). It shows up when a team loses a starting lineman. And it’s also shown up in these start-up leagues the last few years.

Thanks to my buddy Shek for reprising this with Paxton Lynch resurfacing in the USFL.

Yeah, we all saw what happened.

Brian Fluharty/USA TODAY Sports

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

Bill Belichick is 70!

The greatest to ever ride an NFL sideline with a headset on became just the fourth guy in league history to get to his 70s as a head coach, joining George Halas, Marv Levy and his contemporary Pete Carroll. And the natural next question is how much further he plans to take this. I think, to that end, there are four things to consider here …

1) Belichick still loves doing it. That much is obvious. I had someone there tell me that this offseason he’s actually working more than he has in the recent past, which only speaks to the fact that, to borrow paraphrase an old Levy-ism, there really isn’t any place he’d rather be.

2) Being in one place for 22 years makes day-to-day life easier. Belichick’s program is the Patriots at this point—he’ll draft guys next week who weren’t even alive when he took the job in 2000. That doesn’t make the operation turnkey, but it does mean that if he wants to run a meeting or two over Zoom from Jupiter or Nantucket, he can do it. Which allows him to do the things people in their 70s generally want to, while also continuing with his life’s work.

3) His sons, Stephen and Brian, work for him, and that allows him to spend an amount of time with them that most dads in their 70s would only dream of being able to get with their kids.

4) Belichick currently has, including playoffs, 321 wins. That puts him third all-time, behind only Don Shula (347) and George Halas (324). He’ll pass Halas at some point, probably relatively early, this year. He’s 26 behind Shula. It’s fair to think that he should pass him in 2024. And while Belichick would never admit to that being a motivator, I will say there are few people on the planet with a greater appreciation for, or knowledge of, football history.

And then, there’s the Brady factor.

I’ve heard for more than a decade that those around him believe he wants to show he can win with the Patriots without Brady. He got the franchise Mac Jones and a playoff berth last year. The next step is showing that legit championship contention is on the horizon. If Belichick can get there, too, he’ll be in better position to hand something good off to whoever the next guy in Foxborough is—which I believe is another thing he wants to do.

So happy 70th, Bill. I’m guessing we’ll see you around. And for a while longer.