From a dairy farm to a city cafe, we measure the rural-urban divide

Two interviews, 100km apart. Two very different settings.

The first interview is on a Mid Canterbury dairy farm. As Align Farms chief executive Rhys Roberts speaks in a wind-buffeted office, halfway up a milk tanker track, cows emerge from the shed and wander back into the nearby paddock.

READ MORE: * Infrastructure’s bottomless well * What is the youth crime problem we’re trying to solve?

The second interview takes place in a bustling cafe in southern Christchurch. Suit-wearing Research First director Carl Davidson talks and sips his coffee (later, he orders another to go), while pre-schoolers compete with the coffee machine for the prize of highest decibel rating.

What’s surprising about these two conversations is though they’re far apart in many ways, there’s a huge amount of common ground. That’s not to say, however, there’s universal accord on such a complex, emotive subject.

“There’s no better time to be a farmer,” declares Roberts, the Align Farms boss, who grew up in Waikato and has been farming for 20 years. His grandfather, and his great-grandfather, were also dairy farmers.

You have to be a perennial optimist, he says, as you’re dealing with biological systems, climate, animals, people, soil, and living organisms. There’s an elusive goal being chased – “this could be the perfect season”.

Align has six dairy farms in Mid Canterbury, and four dairy support farms for young stock.

The company milks 5000 cows on about 2200 hectares. There’s a small market garden, and Align also owns a yoghurt factory.

The whole operation employs 60 people, 45 of them on the dairy side.

Dairy’s been Roberts’ life, and he loves it. But, oddly, he’s farming agnostic.

He looks out at a fenced paddock of pasture.

“If that land class is better suited to growing pineapples in the future by all means I’ll grow pineapples.” He pauses. “I’d love to grow pineapples.”

He also mulls growing hops, or planting a couple of paddocks in potatoes.

Climate a national issue

That’s the optimism. Roberts then shifts to the challenges.

“I guess we feel a bit like we’re getting told that we need to pay for a prevention of a disease we already have, whilst also trying to prove that we could be the cure.”

He’s talking climate change – something his company felt keenly two years ago when 27 hectares of its farm near Mt Somers was lost – or reclaimed, perhaps – to the river, in floods amplified by climate change.

Agriculture accounts for 49 percent of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. But, says Roberts: “This is a national issue, not just a rural issue.”

We’ll come back to emissions. But for now, is there a rural-urban divide?

“I don’t think we have a rural divide in New Zealand, I really don’t,” Roberts says.

“We have a divide in the way that we interpret our challenges, and at the end of the day, that’s quite common.

“In a highly functional community, you’re going to have difference of opinion. If you don’t have difference of opinion, there’s going to be issues.”

Farmers' greatest concerns

One extreme voice is the lobby group Groundswell, whose founders headed north in a “Drive 4 [political] Change”.

(One protest sign says: ‘WE CAN’T TAKE THREE MORE YEARS OF LABOUR’.)

“Yeah, you could argue going into Auckland with bloody tractors and stuff’s not super-healthy,” Roberts says. “Everyone, ultimately just wants to feel like they’ve been heard. And if people feel they haven’t been heard they’re going to do that type of stuff.

“Good on them.”

Something often heard from farmers is they’re dealing with unworkable regulations. Are farmers really swimming in red tape?

Roberts says though some regions are only just grappling with having to measure and monitor things like nitrogen loss to soil, and livestock emissions, Canterbury has been on that journey for at least a decade.

“We’re probably not putting our hands up saying, 'hey, look, this compliance is coming at us too fast'.”

‘Christchurch, for all its genius, is still a very large, rural town.’ – Carl Davidson, social scientist

Farming used to be a lifestyle, then it became a career, and now it’s a profession, Roberts says. Every cow wears what is in effect a smart watch, to measure efficiency and productivity. Align employs a person to collect and collate data.

The company’s undertaking scientific trials, testing soil carbon, cow urine discharges, and how different pasture species affect methane emissions and milk production.

What gets measured gets managed, Roberts says.

So once you’ve got a number for, say, nitrogen loss, or carbon dioxide equivalents per kilogram of milk solids, farmers pull levers to try to bring the number down.

Environmental standards aren’t new, he says, pointing to Synlait’s “lead with pride” programme, and Fonterra’s “cooperative difference payments”.

What is new, Roberts reckons, is the national conversation about farming over the past five to seven years – so squarely in the time Labour’s been in Government.

They’re labelled “polluters, polluters, polluters”.

“That’s not an engaging tone.”

Though agricultural products traded well under Labour, with a couple of $8-plus payouts per kilogram of milk solids, many farmers feel a National-led Government will support them.

“Everyone wants to be included, and recognised for their strengths and their weaknesses,” Roberts says.

Fonterra may be New Zealand’s biggest company, but it is also the country’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, 86 percent of which come from farm-related activities. The dairy giant just announced a near-tripling of its net profit.

In the Christchurch cafe, Carl Davidson, of Research First, says New Zealand’s a curiosity.

It’s convinced of its enduring rural character, yet it’s one of the most urbanised countries in the world.

According to some figures, more urbanised than the United States, and Australia, it turns out, and up there with Denmark. Most New Zealanders, most of the time, have an urban experience, Davidson says.

This wasn’t always the case.

Not long ago, everyone knew somebody with a farm or had holidayed on a farm. Farms were close to cities. But farm ownership has been corporatised, and there’s been a peri-urban shift to lifestyle blocks.

“It’s really hard for people to understand what farmers do and don’t do – both good and bad.”

When it comes to the urban-rural divide, Christchurch has natural advantages over other places, Davidson believes.

“People in Christchurch are much more aware how much we depend on the rural sector: I think the earthquakes taught us that; the Covid recovery taught us that.

“The reason we’ve done OK is because we’ve got a really strong rural base.”

Professional services are without doubt the largest part of Christchurch’s economy, but Davidson wonders what proportion are serving farm businesses.

“Christchurch, for all its genius, is still a very large, rural town.”

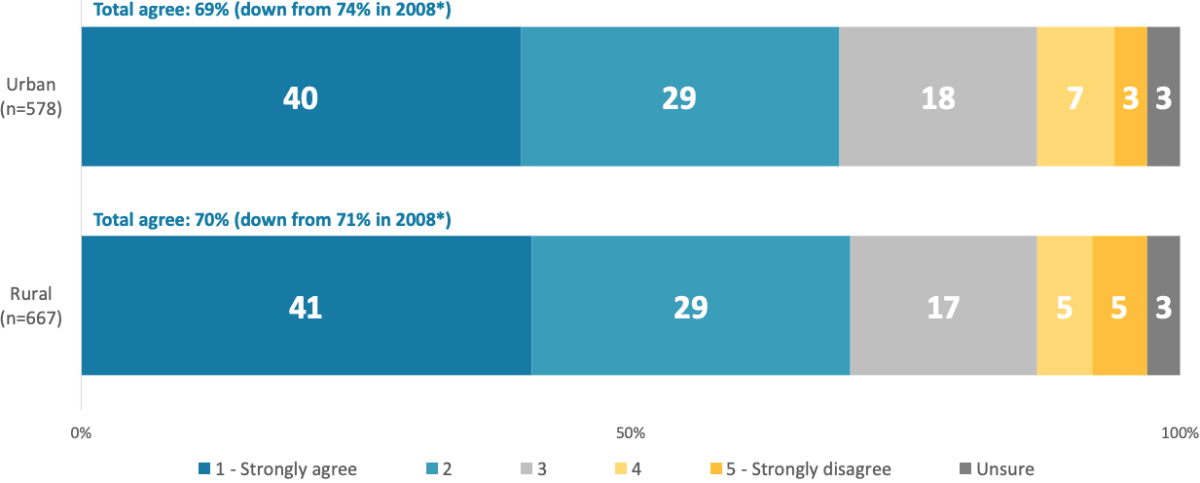

Most agreed that expansion of the primary sector is good for NZ

Davidson’s view is that the urban-rural divide is a construct.

Unsurprisingly, for a numbers man, he explains his position using research – in particular, rural attitudes surveys done by the Ministry for Primary Industries.

“When you look at the data from rural attitudes to everything – climate change, water conservation, whatever – the urban attitudes and rural attitudes overlap, so there’s no change.

“Yep, there are people in the rural sector who have radical views, just as there are in the urban sector.”

Whatever you think of Groundswell, some farmers think no one’s listening to them, Davidson says – although he’s not sure that’s true.

“You’re not going to solve this by having two people standing on either sides of the wall yelling at each other, are you? We’re not going to get anywhere.”

Davidson’s suspicion is rural people think there’s a bigger divide between their attitudes and those of urbanites.

“Probably because they’re listening to the media, or whatever – I don’t know where they’re getting it from. Politicians, perhaps.”

There’s lots of good farming going on, focused on sustainability, Davidson says. But it’s the outrageous examples – cows in waterways, unfenced streams, a lack of riparian planting – that make the news.

“We’re hardly ever seeing the others.”

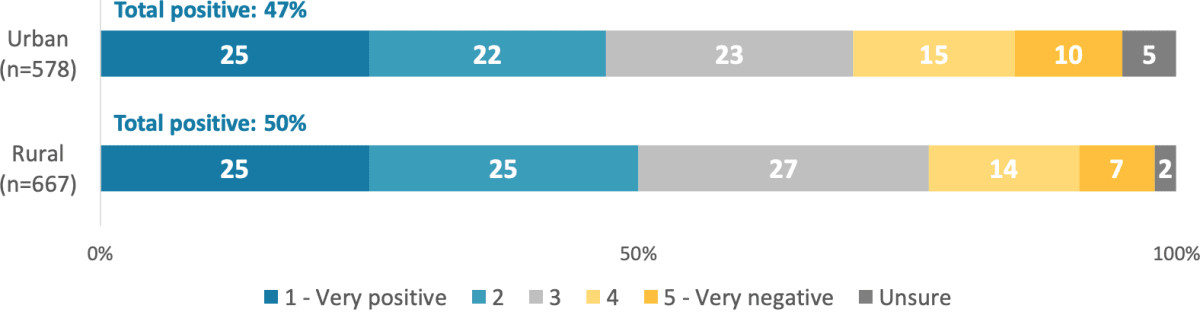

Attitudes to dairy farming

Sticking with the media theme, we talk to Sarah Perriam-Lampp, who, a few months ago, bought two print magazines – Country-Wide and Dairy Exporter.

She burst onto the national stage as co-host of Radio Live’s Rural Exchange programme, with Hamish McKay and Richard Loe, just weeks before the 2017 election. Water was a dominant subject in the campaign.

Newsroom meets her at a cafe in Tai Tapu, a small town just south of Christchurch where her growing media empire is based.

Perriam-Lampp says she found the election six years ago highly emotive. For her family’s six generations farming in Central Otago, “water was survival, it wasn’t intensification”.

“We quickly learned as a sector that we don’t know how to tell our story, because our story is quite complex and technical and scientific, and distilling down into bite-size messaging is really hard. And so since since the 2017 election to now, we still haven’t worked out how to do that effectively, in my mind.”

Living in Auckland, and working in a liberal newsroom unfamiliar with farming, was eye-opening for Perriam-Lampp.

“You learn a lot about the reasons why the media have been that way to date,” she says. “They simply don’t know what they don’t know, and that’s not their fault.”

(In saying that, later she decries what she calls hit-pieces on farmers, and questions whether some reporters have a genuine passion to understand rural issues.)

She believes it’s important for city-based media to get a crash-course in farming – the farming of today, not 30 years ago or what they’re seeing overseas.

Just as newsrooms rely on specialist reporters in science, health and business, they should have strong representation from the rural sector who are able to explain the complexities of how food is produced, and its economic contribution, she says.

Perriam-Lampp saves some tough words for her own.

“The rural media has a huge amount to play in that rural-urban divide rhetoric. And I am really vocal to my colleagues in rural media about how much they contribute to a narrative that may actually be not true.

“You talk to any farmers across the country, I would hand-on-heart say about 90 percent of them think they are hated, and that there is a rural-urban divide. That hasn’t been a constant message in mainstream media, that’s been a constant message in rural media.

“I want to hold them to account for the detriment that they’re doing to mental health of our farmers by reiterating a rhetoric that serves them really well – the them and us.”

It’s confirmation bias, Perriam-Lampp says, and it’s tribal. And sometimes understandable.

The primary sector sometimes feels its identity is under threat, she says, because it’s so strongly attached to the “responsibility and care that they believe they bring on a day-to-day basis”.

“When the identity of the farmer is under attack, they feel under attack.”

A dig-in reluctance

Another who refers to farmers being tribal is the environmental activist Angus Robson, of Matamata.

Social bonds in rural communities can be a great thing, he says, but when it becomes tribal people stop speaking out about problematic issues.

Why have farmers seemingly lost their social licence in recent years? Robson puts it down to extremists within the industry lying about things like climate change – saying it’s not real, or doesn’t matter – and the knee-jerk outrage at valid criticism.

There’s a narrative of a few bad eggs ruining it for the rest. That’s not always true, Robson says.

“There’s a huge amount of damage being done by a great majority of farmers – but they’re not going to say because they’re part of our tribe. And those particular issues are winter grazing in the South Island, and nitrate loss in the alluvial soils of the Canterbury Plains and south.”

Robson is adamant there’s a rural-urban divide. Some of that’s born of ignorance on both sides – for example, city folk who don’t know where their food comes from.

“But they see that the environmental footprints of farming are pretty heavy, whether it’s climate change or freshwater or whatever else, and they think, can’t we just press a button and make this go away?

“Or what they also see is basically a complete, dig-in reluctance by many traditional farmers to doing anything about it.”

An irony is some of Robson’s greatest supporters are farmers.

“They say, stick to your guns, keep doing what you’re doing, be responsible, tell the truth, and work with doable solutions.”

Farming faces a lot of threats, he says, particularly dairying and dry stock (pasture grazing of beef cattle, sheep, and deer for meat, wool, and velvet).

Robson thinks precision fermentation – growing food in a laboratory, basically – poses a greater threat to the industry than regulation, or freshwater and climate change.

Davidson, of Research First, says the farming industry and rural areas face big problems.

It’s already having trouble attracting and keeping staff but he thinks things could get worse.

The lion’s share of Aotearoa’s population growth will likely go to the behemoth of Auckland – known in demography circles as a “primate city” because of its outsized proportion of our population and economy.

This exposes our lack of regional economic development policy, Davidson says.

Demographic projections say most regions in New Zealand are going to eventually stagnate and decline.

Rural areas will therefore face existential questions. How do they keep people in the local community? How do they attract school teachers? Or doctors? At a basic level, how will the community remain viable?

“That’s a huge, long-term problem,” Davidson says.

Farmers and consumers, disconnected

Back to Roberts, of Align Farms, who paints a picture of how his industry has changed.

Farmers used to take signals directly from consumers but now they sell milk to “customers”, such as Fonterra, who on-sell to their customers, such Nestlé. Then there are government regulators, bringing in rules for things like winter grazing.

For an industry whose biggest problems used to be finding good soil, accessing reliable water, and plentiful sunshine, there seems to be an avalanche of expectations, all of a sudden. Several avalanches, actually.

Fonterra is expected to announce an on-farm emissions target by the end of the year. (In July, the cooperative said the target would be announced “shortly”.)

Switzerland-headquartered Nestlé, the world’s biggest food and beverage company, has promised to reduce emissions by 50 percent by 2030. By then, it intends to get half its key ingredients from farms with regenerative agricultural methods.

Back at home, New Zealand’s climate target for biogenic methane emissions is a 10 percent reduction by 2030, on 2017 levels.

“They all have a different template and they all need the same information written down three times,” Roberts says. Accountability’s important, he says – the problem is duplication.

Pertinently, there’s an election on.

The National Party has promised not to put a price on livestock emissions until at least 2030, while Labour, if elected, wants pricing to start in 2025.

Roberts says farmers are in a consumer-driven market and, at this stage, it’s not clear if consumers are willing to stomach the increase in food prices necessary to drastically cut emissions.

A tax on emissions won’t reduce farm emissions, he says.

The Climate Change Commission’s review of a proposed government pricing scheme, through industry partnership He Waka Eke Noa, said it wouldn’t lower emissions – but that’s because subsidies were too generous.

Roberts says: “Research and development, investment in science, will ultimately get us there faster.”

Another concern of the Climate Change Commission was New Zealand relying on as-yet unavailable technologies to reach its 2030 methane reduction target.

‘We can’t ignore the need to do more and reduce emissions, where possible.’ – Charles Finny, former trade negotiator

There’s a historical, scientific bunfight over the pace of methane reductions.

That fight might just have been intensified after a new working paper, published in September, questioned the wisdom of cutting our high methane emissions, as the cooling might offset cuts from longer-lived gases.

It was seized on by the industry group Dairy NZ – which funded the research with Beef + Lamb and Federated Farmers – as “raising serious equity concerns for farmers”.

Roberts, of Align Farms, says: “Are farmers completely convinced that we have consensus on the science? You’d argue probably not.”

The problem isn’t that farmers don’t want to pay for their emissions, he says, but the lack of consensus between scientists, politicians, and consumers.

Roberts then repeats a line often used by industry groups to try to slow climate action – that if there’s no net increase in cow numbers, then there’s no impact on global warming.

“We’re going to go around the stirring bowl a few more years yet before we ultimately come to consensus.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says deep cuts are needed to all greenhouse gas emissions to avoid dangerous climate change.

A pivotal 2018 journal article by Oxford University’s Myles Allen, a co-author of the aforementioned working paper, says constant, ongoing high levels of short-lived climate pollutants emissions “may still represent an important contribution to warming to date and/or a mitigation opportunity”.

An outside view

Let’s widen the lens somewhat.

Too often Kiwis are guilty of talking about ourselves – whether it’s rural versus urban, or each group within themselves.

How New Zealand’s perceived overseas is crucial because 85-90 percent of our dairy, meat, fruit and vegetable production is exported.

Charles Finny is a former trade negotiator and diplomat, who’s chairman of the Wellington government relations firm Saunders Unsworth. When Newsroom calls, he’s walking the streets of Invercargill.

He says overseas consumers will factor emissions into their buying decisions. Though it’s not a huge issue in markets such as China right now, it’s of growing importance in Europe.

Climate policy is already being factored into trade agreements.

Fortunately for New Zealand, Finny says, it’s reasonably carbon efficient.

“But we can’t ignore the need to do more and reduce emissions, where possible, because the integrity of our product, if we’re going to be maintaining a good price, is going to be essential.”

Whatever happens in next month’s election, Roberts, of Align Farms, says it would be foolish for the next Government to start tearing up farm regulations.

“That’s not going to help anyone. We’ve got to keep moving – we can’t go back to where we were.”