College and university campuses across the U.S. have seen polarization and unrest since the Israel-Hamas war began with the Hamas attack on Israeli civilians on Oct. 7, 2023. Students and faculty have held protests and rallies, argued on social media and signed statements, some of which have increased mistrust and turmoil on campus. Some college leaders have weighed in on the war, which has not necessarily calmed their campuses. At the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, scholar David Mednicoff chairs the Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies. He spoke with The Conversation’s senior politics and democracy editor, Naomi Schalit, about how he and his colleagues and university leadership have tried to deal – as an educational institution and a community – with a highly charged situation on campus in which there is pain, anger and anguish on both sides. Mednicoff aims to contribute to an approach he believes central for his community: respectful discussion, listening and seeking understanding, and the chance for open minds and hearts in the middle of conflict.

What has been going on at UMass Amherst during this crisis?

Immediately after the Oct. 7 attack, many Jewish students and community members with ties to Israel felt shocked, scared, confused and worried, and sought support from the university.

Soon after the attack, an active UMass student chapter of Students for Justice in Palestine began demonstrations and other events. With war looming, its members were also feeling upset, scared, confused and worried – very parallel feelings.

Our graduate student union quickly issued a statement, since toned down, that blamed the attacks on Israel’s past policies, and appeared not to acknowledge Israel as a nation. That statement upset many Israeli and other members of the campus community, some of whom lost people they know on Oct. 7.

We’ve seen public activism from several groups in the university community that decry the unequal power between Israel and the Palestinians, and feel solidarity with Palestinians. On the other side, organizations with connections to Israel held vigils and discussion groups. Some Jews at UMass found pro-Palestinian rallies and specific chants frightening, and possibly antisemitic. Some pro-Palestinian activists were doxxed online, threatened or smeared by right-wing news organizations. Many students in my department expressed feeling unsafe.

That sounds representative of what’s been going on at colleges and universities around the country. At a certain point, the university’s leadership felt like it should speak?

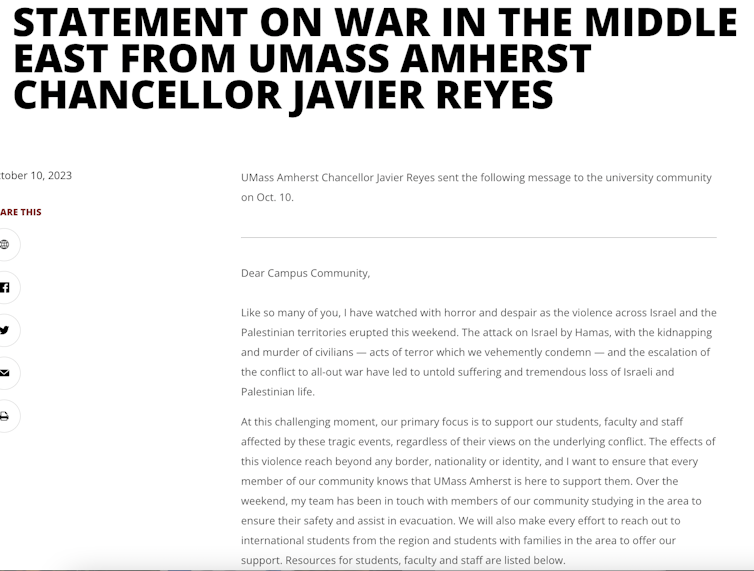

The chancellor, Javier Reyes, issued a statement very quickly after the attacks. That statement attempted to empathize with all students, staff and faculty who felt concerned and scared after the Hamas attack and who anticipated a full-scale Israeli war on the Gaza Strip as a result.

The chancellor’s initial statement demonstrated the university’s broad concern for the impact of Oct. 7 on campus. It was clear in recognizing Hamas’ responsibility for its brutal and murderous attack on Israel. It also recognized that many people who cared about Palestinians would be grieving.

Many campus stakeholders saw the statement as appearing not to take sides in a conflict that provokes contentious reactions. I think the statement also spoke to the many UMass community members who felt deep concern for people suffering unfathomable loss on both sides in this new wave of conflict.

The UMass administration may not wish to weigh in on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict because they see no campus communal consensus, or it is unclear that UMass can affect the issue directly. I am sure university officials care about this conflict. But they also may fear that taking a position on a genuinely contested global issue will make some members of our community feel unrepresented or discouraged from taking part in the robust education and contentious conversation on hard issues that help define the univerity’s mission.

Those are really values, not politics, that you’re talking about, aren’t they?

American universities face major challenges from external political groups, particularly on the right. The idea that open, well-informed, reasoned discussion can be central in the U.S. or any society that calls itself democratic has itself become contested. Not only is what universities do challenged politically, but I fear we are losing ground. Whether we call it politics or values, defending and creating space for open, evidence-driven education, free discussion, empathy and tolerance is central in the struggle here and now to maintain democracy against authoritarianism.

Do you mean it’s a political statement to say “We value respectful discussion of different points of view”?

Right. It’s clear that there are a lot of folks who want to see universities like mine take a specific stance on something like Middle Eastern politics. For people who care about Palestinian rights and the current onslaught of deaths from Israel’s military, this can seem more urgent now than anything else. I understand colleagues who think that UMass’ institutional potential to have a material impact on Palestinian lives is worth the risk to our harmony or community members’ security. Yet I also understand that a university might center the struggle to maintain our institutional autonomy, community members’ trust and diverse speech as a primary set of political responses.

What has your department done during this period?

I sent out a statement to our constituents that echoed the chancellor’s statement prioritizing concern for members of the community. It underscored the tragedy and sadness of death and disruption on both sides of this conflict. I was careful not to suggest a specific political posture because my position requires me not to shut down members of my community who may have different viewpoints. My colleagues and I have tried to be open to hearing our students’ concerns, even when some are angry at us for not taking a clearer political stand.

Then my department convened two public talks by experts who live in our area. First, Dr. Ahmad Khalidi, a Palestinian academic and policy activist with decades of relevant experience, provided one perspective. Dr. Khalidi spoke eloquently on current and ongoing conditions Palestinians face to the several hundred attendees and 70 or 80 people on Zoom.

More recently, we featured the perspectives of a local Israeli, Dr. Jesse Ferris, who helps run a leading Israeli think tank, the Israel Democracy Institute. This event also had very strong attendance.

Both events were civil and thoughtful and ended with a set of questions from the audience that indicated divergent perspectives in the room. After the second talk, several students initiated a discussion – indeed, a respectful argument – on whether or not Israel’s current military operations could be justified.

From my vantage point, as someone who sees many people on campus in pain and many more not knowing what to think, bringing in expertise that can encourage people to engage with one another, potentially across divides, seems needed. So that’s what we did.

The group Students for Justice for Palestine, or SJP, held a large rally that ended up in a sit-in at the university’s administration building. Over 50 arrests were made when the students didn’t leave as the building was officially closed. What did that mean for efforts to foster constructive discussions?

I appreciate that the chancellor and his team met personally with students from SJP right after the rally and later with a group of Jewish students. The statement that the chancellor issued a day after the SJP rally seeks to balance concern for the campus community with aligning the university strongly with free speech, even when such speech is upsetting, as the rally felt to some.

The statement once more did not take a specific position on the Middle East or on the perspectives advanced by campus groups. The chancellor focused on defending the right of protesters, and everyone, to speak.

His statement did not make everyone here happy. Yet opening himself and UMass Amherst to criticism by championing vigorous debate on a far-flung, divisive conflict affirms what our university stands for. We are a place for discussion, diversity of opinion and sometimes difficult conversations about hard, hard problems.

David Mednicoff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.