Body language experts have been having a field day since the U.S. presidential debate. They want us to believe that it’s possible to tell what Donald Trump and Kamala Harris are thinking, but not saying, just by looking at their body and facial movements.

As the election approaches, every move the candidates make will be “decoded” and broadcast in the media. But how good are these analyses?

For over 10 years now, I’ve been looking at the influence of beliefs on non-verbal communication, in the particular context of legal trials. My work has shown that when it comes to judges assessing the credibility of witnesses, some apply unsubstantiated beliefs, or beliefs that have been proven false. These beliefs can then lead them to disbelieve honest witnesses and to believe dishonest ones.

À lire aussi : Regards fuyants, nervosité, hésitation... Comment le non-verbal peut influencer la justice, à tort

Non-verbal communication

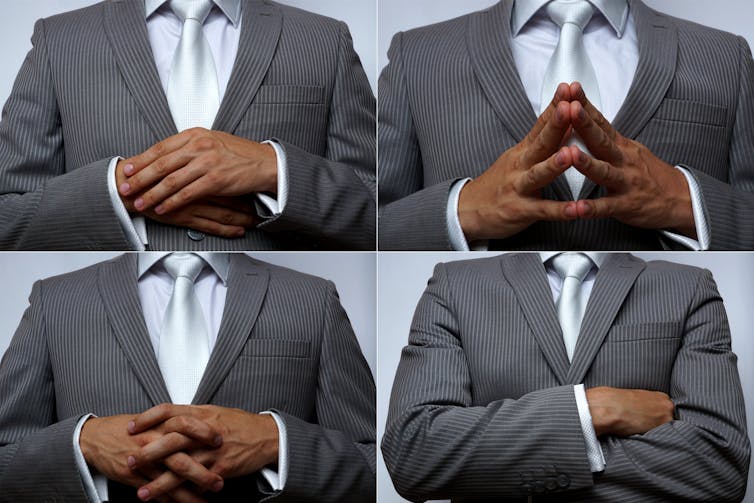

Non-verbal communication, i.e. communication by means other than words, has been the subject of thousands of scientific publications for decades now.

From the role of facial expressions in developing a bond of trust between doctors and patients, to the impact of gestures in public speaking and assessing the credibility of witnesses in trials, non-verbal communication is studied in a multitude of disciplines, including communications, psychology, criminology and computer science. Researchers around the world publish peer-reviewed articles on non-verbal communication.

Here are some of the findings that merit attention:

First, contrary to what body language experts claim, there is no scientifically validated dictionary that can be used to “read” body and facial movements from a simple glance, like words in a language.

And second, there is no “Pinocchio effect,” i.e. body or facial movements that demonstrate absolutely who is honest and who is dishonest. Yet, many people believe the opposite.

For example, in various countries people believe that looking away is a sign of lying. But this belief is wrong. In reality, honest people can look the other way for many reasons. In some cultures, for example, looking away is a sign of respect. Nervousness and hesitation are also associated with lying, whereas in reality, honest people can be nervous and hesitant. Such beliefs are conveyed by individuals who, either formally or informally, claim to be experts in body language.

Dishonesty, authenticity, competence

On traditional and social media, including YouTube, body language experts “decode” the body and facial movements of celebrities, whose slightest gestures are said to show they are either lying, being authentic, or showing themselves to be competent. The same exercise is carried out on politicians, both in public speeches and debates. But the conclusions these body language experts draw from observing body and facial movements are pretty questionable, if not totally frivolous. What’s more, their analyses are deeply flawed.

For instance, these experts sometimes quote science as an argument of authority, but then when science doesn’t actually support them, they contradict it. Body language experts might say there is no “Pinocchio effect,” but they’ll watch videos, press pause and point out behaviours that supposedly demonstrate what a politician is thinking, but not saying. Proponents of such analyses even go as far as harassing and trying to intimidate researchers who attempt to set the record straight.

Body language experts sometimes call for caution. Yet, while on the surface these appeals might seem to make sense, in reality they don’t apply. For example, experts recommend looking at changes in the behaviour of male and female politicians compared to their “normal” behaviour. But how could this be done, in practice? When exactly should changes in behaviour be considered? Should a small change be given the same weight as a big one? Should a change in facial expression be given as much weight as a change in posture? Body language experts have little to say about this.

In addition to changes, body language experts say that they need to observe many body and facial movements before drawing any conclusions. However, considering several body and facial movements that have no value does not increase the value of an erroneous judgment.

Body language experts’ analyses can certainly be entertaining. However, in disseminating unsubstantiated beliefs, or beliefs that have been proven false, body language experts end up contributing to an ecosystem of misinformation. Their reach depends on the attention they receive from traditional media and the visibility they receive from social media.

The danger of false certainties

The popularity of unsubstantiated beliefs about non-verbal communication, or beliefs that have been proven false, is not a trivial issue. Voters could develop erroneous beliefs about politicians as a result. And when these beliefs are adopted by people in positions of authority, such as police officers and judges, the consequences can be disastrous.

In the U.S., for example, one interview technique suggests to police officers that movement in the chair, and looking away should arouse suspicion. But such beliefs have no value and can actually reinforce the perception of guilt in individuals who, in reality, have done nothing wrong.

Worse still, in trials, these questionable observations can result in honest witnesses being judged as dishonest, and dishonest witnesses being judged as honest. In the written judgments from Canadian courts that I have studied, some judges have decided that child victims of sexual crimes were not credible because they did not show an expected behaviour or did show an unexpected behaviour. For example, children who showed no emotion when they testified were not deemed credible. However, not all children react in the same way. In fact, “children in forensic interviews often display neutral affect at disclosure, and most do not cry.” But some judges believe differently.

In short, even if the “body language experts” truly believe what they are saying, their analyses of politicians — however entertaining these may be — are not always harmless. In the name of the public interest, we should be looking closely at the attention they receive and the visibility they get in the media.

Vincent Denault ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.