THERE were tears in the eyes of even the toughest of blokes as Molycop workers walked off the job for the last time.

Friday marked the nail in the coffin for Newcastle's 'steel city' identity, as the curtain fell on more than 100 years of steel-making at Waratah.

For veterans like steel-making team leader Paul Berthold, who marched out shoulder to shoulder with his colleagues after 33 years on the job, it was an emotional end of an era.

"I think you can see the tears already coming out, it's very sad to lose your work mates," he said.

"After 33 years we've had a lot of long-term friendships, we spend more time with the blokes at work than we do at home with our own families, so it's been a pretty tough time personally, you can see the tears."

Molycop announced in September last year that it would cease steel-making operations at Waratah, leaving 250 workers at the site without jobs.

Many have since found other employment, others took redundancies and are looking forward to retirement, but for some, like Mr Berthold, the future remains uncertain.

The company declined to comment when contacted by the Newcastle Herald on Friday, but Molycop Australasia president Michael Parker previously said the difficult decision was one they believed would best position the company for success in the long term.

Cleaner Tracey Darby's eyes welled up as she watched the men who had made her feel like "one of the boys" walk out.

"It was an emotional day, we've been here for five years and so these guys are like family, big brothers to us," she said.

"I think a lot of guys have got work but it's the young ones I'm more concerned about, they're just starting a family, buying a house, no job, they're the ones I'm concerned about."

Australian Workers' Union (AWU) NSW branch secretary Tony Callinan said shuttering the steel mill had dealt a death blow to Newcastle's 'steel city' identity.

"It's a very sombre occasion, some of our members have been here for decades, for some of them it's the only job they've ever had," he said.

"It's the end of an era for the Hunter and Newcastle, the last steel maker in the region, it's a real sad day.

"It is a real part of our history, this is one of our last 'old school' steel shops, this was a really strong union site, they all stuck together, they held union values because of the decades of struggle here and it was definitely part of the community."

Mr Callinan said the steel mill closure raised concerns about Australian's sovereign capability, especially after the pandemic demonstrated issues with relying on imports.

"It's a real long-term problem for the country's future I think," he said.

"It is a definite loss of skills and it's a potential long term problem, we don't make steel here, we are completely reliant on imports and we can see with some of the issues the world is currently facing with wars and uncertainty in other regions - if we can't make it ourselves and we need it, where do we get it from?"

Molycop did handle the situation well, Mr Callinan said, with some workers walking away with good severance packages and others moving into new careers after the company facilitated a jobs summit.

"We've made the best of an extremely bad situation," he said.

"I think it's a sad realisation but I don't think we can call ourselves the 'steel city' anymore, it's a badge we're going to have to lose."

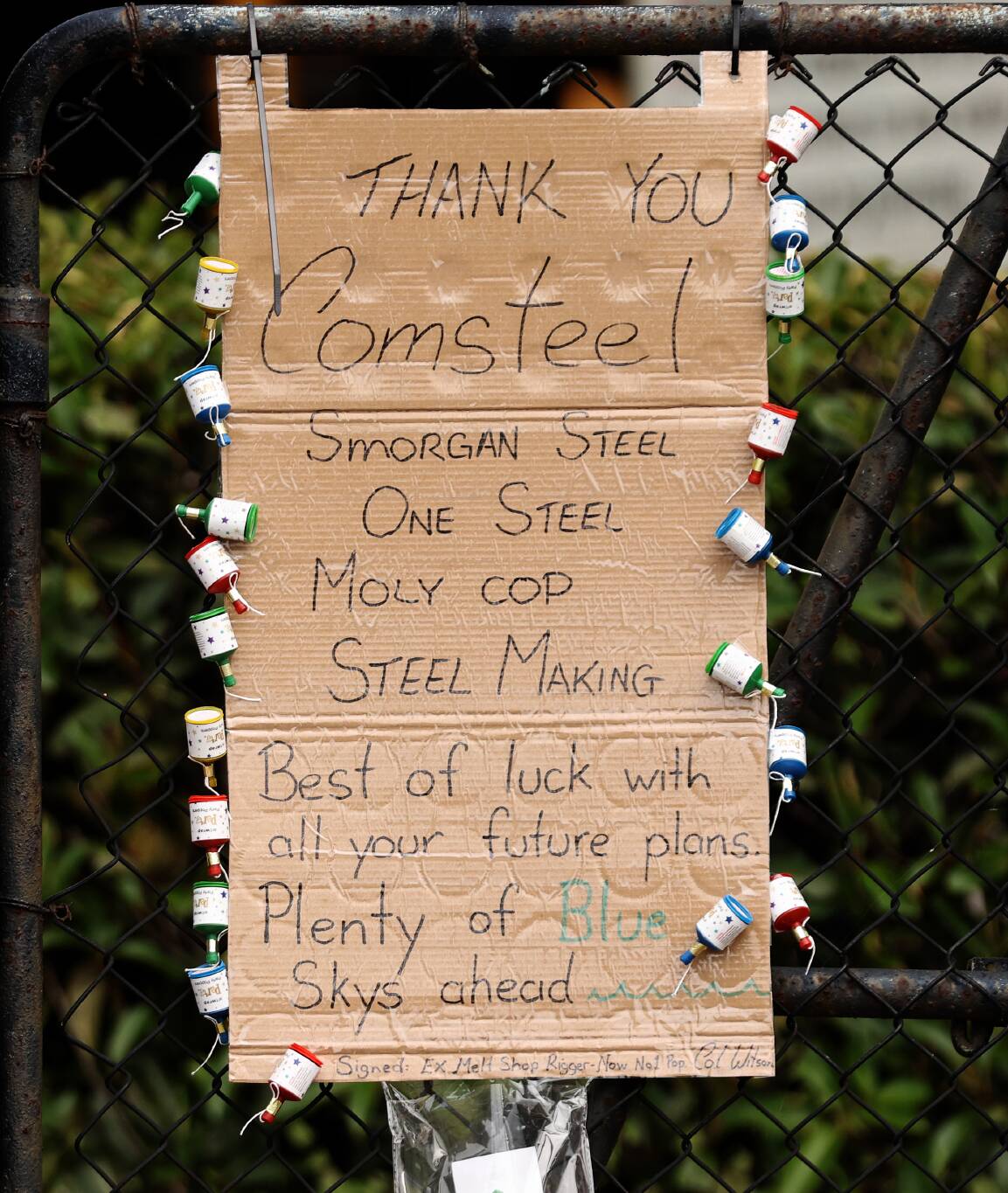

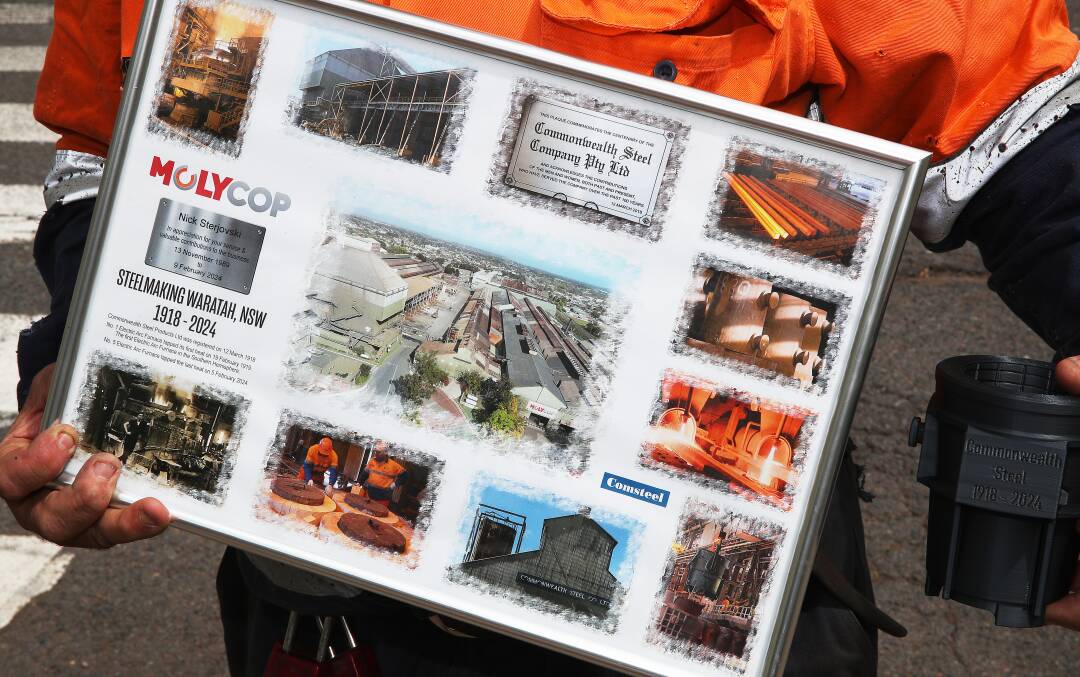

Formerly known as the Commonwealth Steel Company, or 'Comsteel', Molycop celebrated a centenary of steel-making in Newcastle about five years ago.

The company has passed through the hands of some of the largest names in national and international manufacturing, from BHP to Kerry Packer's Australian National Industries, to Smorgon Steel, One-Steel and now the Moly-Cop Group.

The site opened in Waratah in 1918 with 140 employees, by 1939 the workforce had grown to 600 - reaching more than 3,200 at the height of war production.

In the last 100 years the company has employed and trained more than 20,000 men and women.

Generations of local families have walked through the gates and for many, it provided security in uncertain times.

During the depression era, the business moved to part-time operation to hold the workforce together until they could be employed again full-time.

The Waratah plant makes grinding balls for the mining industry to grind down ores, and railway wheels still supplied under the Comsteel brand.

It's the country's only railway wheel manufacturer and has a strong presence in the domestic market, making about 40,000 wheel and axles sets a year in 2018.