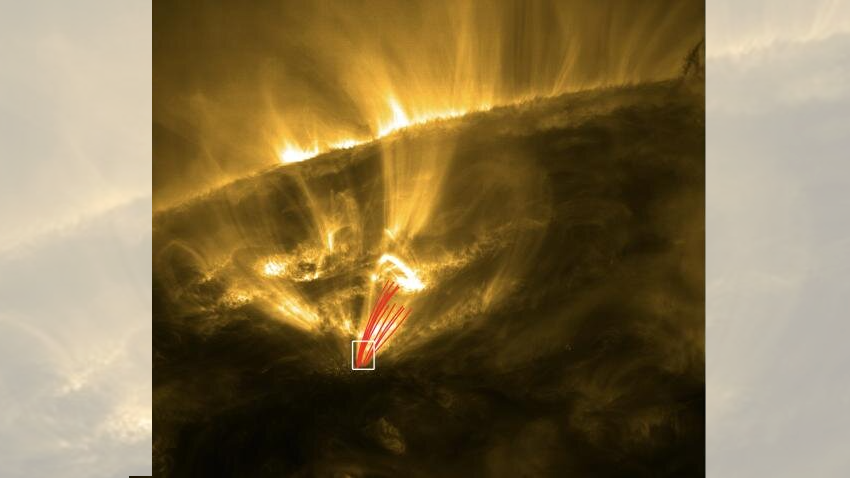

In a startling case of star-ception, our sun, which is a star, appears to have its own "shooting stars" streaking through its white-hot atmosphere.

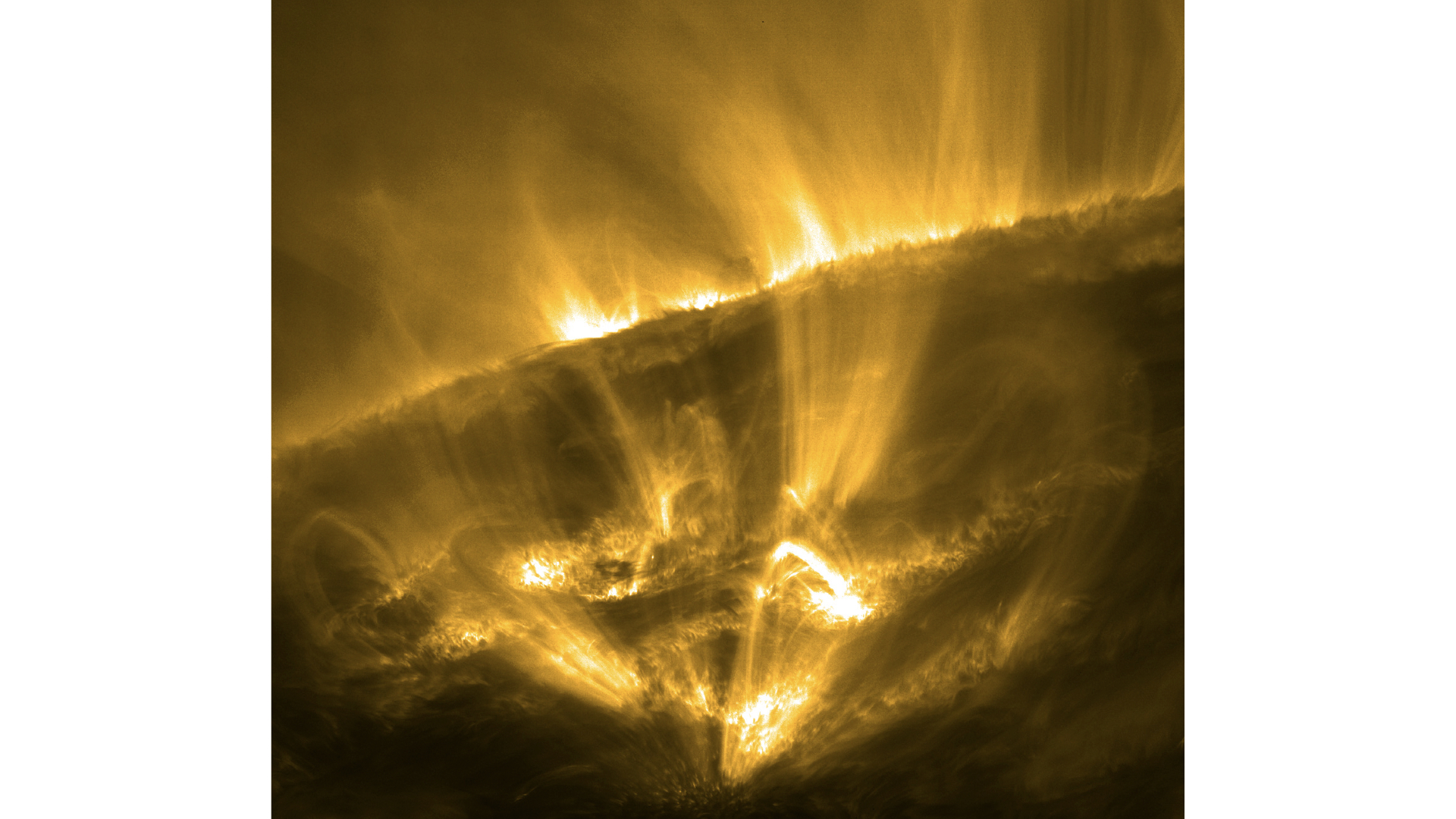

Technically, these solar "shooting stars" aren't stars at all — they're fireballs created by a phenomenon known as coronal rain. During this process, hot plasma cools and condenses in the sun's corona, the outer layer of its atmosphere.

The corona itself is unimaginably hot. It burns at upwards of 2 million degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 million degrees Celsius), according to NASA. This is hotter than the sun's surface, which is a relatively mild 10,000 F (5,500 C). But when cooler pockets form suddenly in the corona, the atmosphere's diffuse material rapidly condenses into clumps of plasma.

Scientists made the amazing discovery using data from the European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter (SolO). The researchers will present the findings, which are currently available as a preprint on arXiv, at the National Astronomy Meeting at Cardiff University in Wales later this week.

SolO was a mere 30 million miles (49 million kilometers) away when it observed coronal rain forming — among the closest any probe has gotten to the sun.

SolO's data showed that these dense plasma balls can reach up to 435 miles (700 km) across. Once they become too heavy, they fall towards the sun's surface. Unlike shooting stars on Earth, which occur when rocky or icy space debris burns up in the atmosphere, scientists think that most of these objects remain intact as they fall, because the sun's magnetic field lines act as guide rails to help funnel the plasma downward.

If humans could stand on the surface of the sun to take in the phenomenon, we would be in for some pretty stunning stargazing, the researchers said.

"We would constantly be rewarded with amazing views of shooting stars," Patrick Antolin, an astronomer at Northumbria University and lead author of the study, said in a statement. "But we would need to watch out for our heads."

As missions such as SolO and NASA's Parker Solar Probe — which made a daring plunge through the sun's atmosphere in June — continue to study the sun's surface and corona over the next few years, scientists expect to learn even more about coronal rain and other strange solar phenomena.

Solar weather phenomena, such as sunspots, solar flares and waterfall-like eruptions of plasma, have been on the rise over the past several months, as the sun gears up for its period of peak activity, known as solar maximum. Some astronomers predict that the solar maximum will come sooner and hit harder than NASA's previous estimates, with the solar maximum potentially arriving in late 2023.