Drummer John Bonham was the heartbeat of Led Zeppelin. When his great heart stopped the life went out of the band. It was a tragedy for rock music as well as for friends and family when he died at the age of 32 on September 25, 1980.

After several personal tragedies had rocked the band in the mid-70s, it seemed as if Zeppelin were poised to make the ultimate resurgence. Instead it all came to a dramatic end when John died in the throes of rehearsals for what would have been the band’s biggest tour in years.

To understand why Bonham died so young we must also understand the pressures of life with the greatest rock band in the world. Being in Zeppelin brought him great rewards, fame and success, but it also undermined his personality and health.

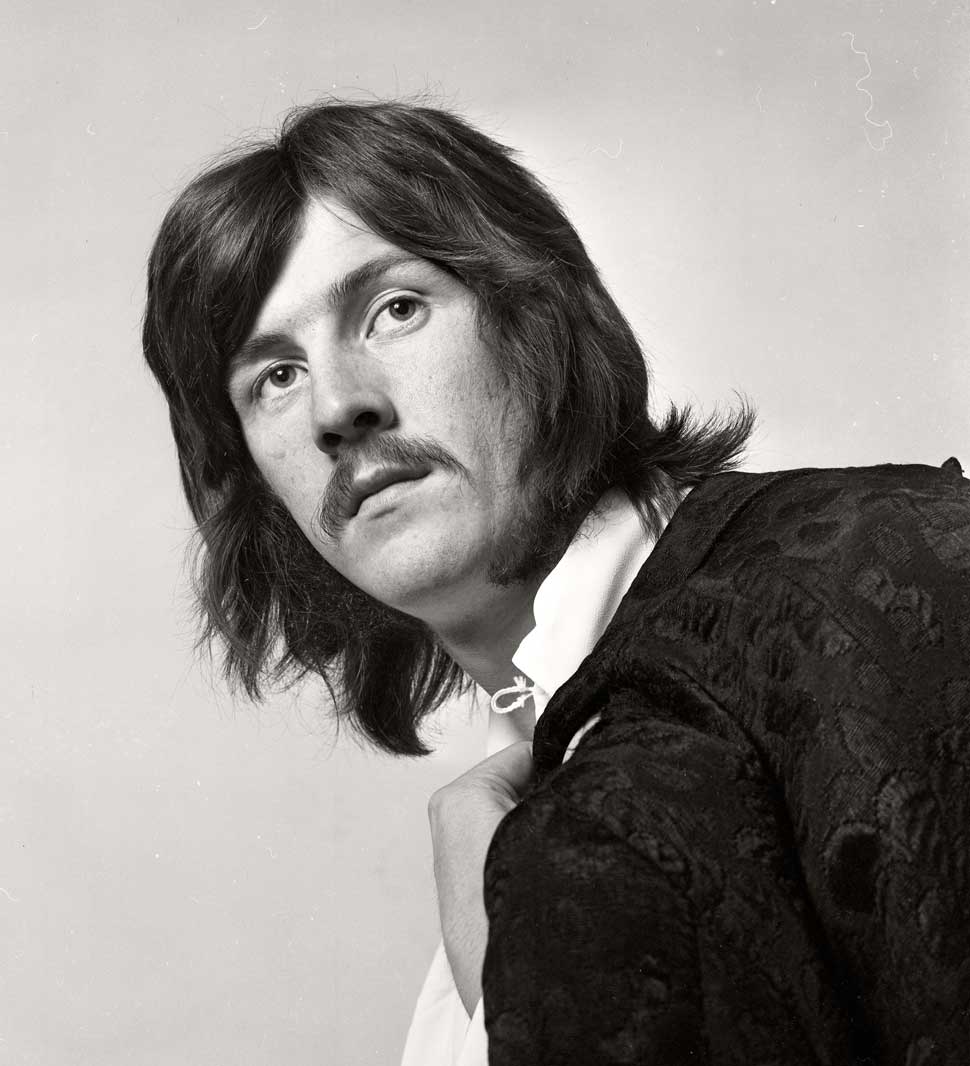

It was a wonderful, life-changing day when the lad from the Midlands agreed to join Jimmy Page’s new band in 1968. Down-to-earth, jovial and generous, John Bonham was the last person many thought would succumb to the rock’n’roll circus. A former builder and carpenter who taught himself to become a powerhouse drummer, he had to be convinced that the New Yardbirds, as Page’s new band were originally known, would ever amount to much.

He agreed to join only after a deluge of pleading telegrams from manager Peter Grant, originally telling his then employer Tim Rose: “No way [am I leaving]. Not only do I love this life, but the money’s too good.”

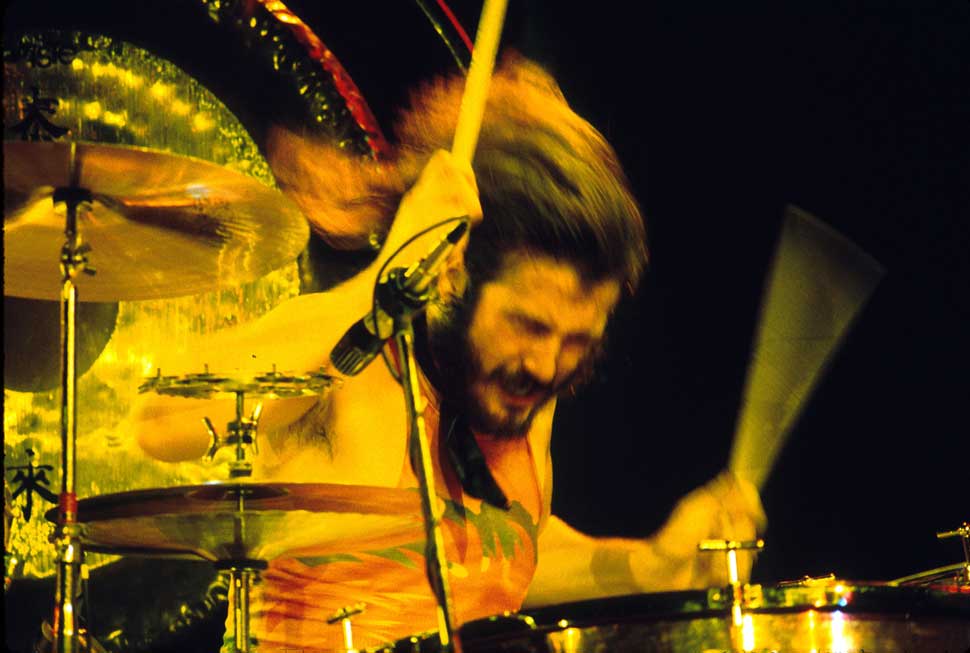

Yet Bonham didn’t get to become the drummer in Led Zeppelin by being the shy and retiring type. He attacked his kit with gusto. But despite his image as a wild man of rock, his attempts to emulate the manic destructive intensity of his pal Keith Moon, of The Who, did not come naturally. He was hard-working and had a huge appetite for life. When he became hugely wealthy from the success of Led Zeppelin he indulged in his passion for fast cars but also spent wisely, creating a happy home for him and his family at the Old Hyde in Worcestershire.

For John Bonham there was no place like home. He hated flying and sitting around all day waiting for a gig. The endless Zeppelin tours he had to go on became a drain on his stamina and confidence. There was the adrenalin rush of playing explosive music every night to thousands of screaming fans, but after that came the need to unwind – usually in a succession of faceless hotels and bars. Life became a blur of rioting fans, speeding limos, booze and groupies. It was fun at first, but powering-up the Zeppelin machine soon became a daunting task.

John Henry Bonham was born in Redditch, Worcestershire, on May 31, 1948. His father Jack ran a building company and employed both of his sons, John and Michael. Aged five John began to show interest in music. At home he began drumming on a bath salt container fitted with strands of wire on the bottom to make a crude snare drum. After adding pots and pans to his armoury, when he was 10 his mother got him a real snare drum. Then his dad bought him a complete kit.

As well as working for his dad as a builder, John drummed with local bands. The Beatles era was dawning, but Bonham had a taste for jazz drummers like Gene Krupa, Joe Morello and Sonny Payne; he loved their stick-twirling showmanship. He took lessons, but developed his own hard-hitting rock’n’roll style.

“Drumming was the only thing I was any good at and so I stuck at it,” he said later. “I always worked hard all the time. When I was 16 I went into full-time music, but I’d have to go back to the building sites to earn money to live. If there were no gigs, there was no money.”

He began playing with his bare hands (a technique he would use on his showpiece Zep song Moby Dick). He also developed a fast bass-drum pedal technique inspired by Carmine Appice, with whom he would form a strong friendship, helping hook Appice and bassist Tim Bogert up with Jeff Beck in Beck, Bogert & Appice.

“It was John who told Tim and I that Jeff Beck wanted to form a band with us,” Appice recalls. “That was after he’d played with Jeff at the Singer Bowl and had taken all his clothes off while playing, which was really wild as my parents were backstage watching the gig. I had to explain to them why! What a night.”

As he gained confidence he would go up to a bandleader and say: “Your drummer’s not much good, is he? Let me have a go. I’ll show you.” He would then take over the hapless drummer’s kit, pound it to bits, and take the guy’s gig.

In 1965, at the age of 17, he married his girlfriend Pat Phillips. As money was tight they lived in a caravan that was owned by John’s father. Later they moved into a high-rise flat in Dudley (where they were actually still living when the first Led Zeppelin album was released).

He joined A Way Of Life, who recorded some demos in a Birmingham studio. The band also included Dave Pegg, who would later go on to play with Fairport Convention. Bonham played so loudly that he was told he was “unrecordable”. He was also told there was no future in playing so loud. Some years later he sent the manager of that studio a Led Zeppelin gold disc with a note saying: ‘Thanks for your advice.’

In 1965 he joined the Crawling King Snakes, where he met Robert Plant, who thought Bonham was a flash whiz-kid. Despite much banter and rivalry the two of them became firm friends. Bonham left the Snakes after a few months to rejoin A Way Of Life. Plant and Bonham were then reunited in the third and final line-up of Plant’s group Band Of Joy in January 1967, wearing the new hippy fashion of kaftan, beads and bells.

At one memorable gig at the Queen Mary Ballroom in Dudley, as the Band Of Joy encored with Tim Hardin’s If I Were A Carpenter, Plant performed a blueprint of what would become his trademark libidinous performance of Whole Lotta Love, wrapping his leg around the mic stand and simulating a sexual act. It proved too much for Bonham’s mother Joan, who strode to the front of the venue demanding at the top of her voice: “John, you get off those drums now! You’re not playing with that boy, he’s a pervert!”

The drummer quit again in May 1968 to back visiting American singer Tim Rose on a UK tour, performing songs including Morning Dew and Hey Joe and earning £50 a week.

“The sad thing about it,” says Tim today, “was that we never managed to record anything together. When John started with me his timing was a bit erratic. His 4/4 timing could vary between 3 and 3/4 and 4 and 1/4.”

One person decidedly more impressed was a youthful Phil Collins, who caught Bonham with Rose at London’s Marquee.

“Within the first few minutes I was dumbstruck by the drummer,” he says. “He was doing things with his bass drum that I’d never seen or heard before. He then played a solo and again I’d never heard or seen a drummer play like that. He played with his hands on the drums – I later found out that as a bricklayer he had very hard hands, and it was obvious from seeing him solo that night. I vowed to keep an eye on this guy Bonham and I followed his progress. He was, even then, a major influence on my playing.”

Meanwhile, down in London, Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones and Peter Grant were putting a band together from the ashes of The Yardbirds. They persuaded Robert Plant to join, who in turn recommended Bonham for the gig. The drummer took some convincing, but within weeks he had joined Page, Jones and Plant in the studio. He told astonished mates back in Birmingham that he had just earned £3,000.

The new band proved a magical team. John Paul Jones: “The first time I ever met John was in a tiny basement room we had rented in Lyle Street. We just had loads of amps and speaker cabs there that had been begged, borrowed or stolen. The first thing to strike me about Bonzo was his confidence, and you know he was a real cocky bugger in those days. Still, you have to be to play like that. It was great, instant concentration. He wasn’t showing off, but was just aware of what he could do. He was rock solid.”

At first Bonham’s playing was too busy however, and he ignored warnings from Page to “keep it simple”. Peter Grant strode over to Bonham and asked: “Do you like your job in this band?” The drummer nodded. “Well do as this man says. Behave yourself, or you’ll disappear. Through different doors.”

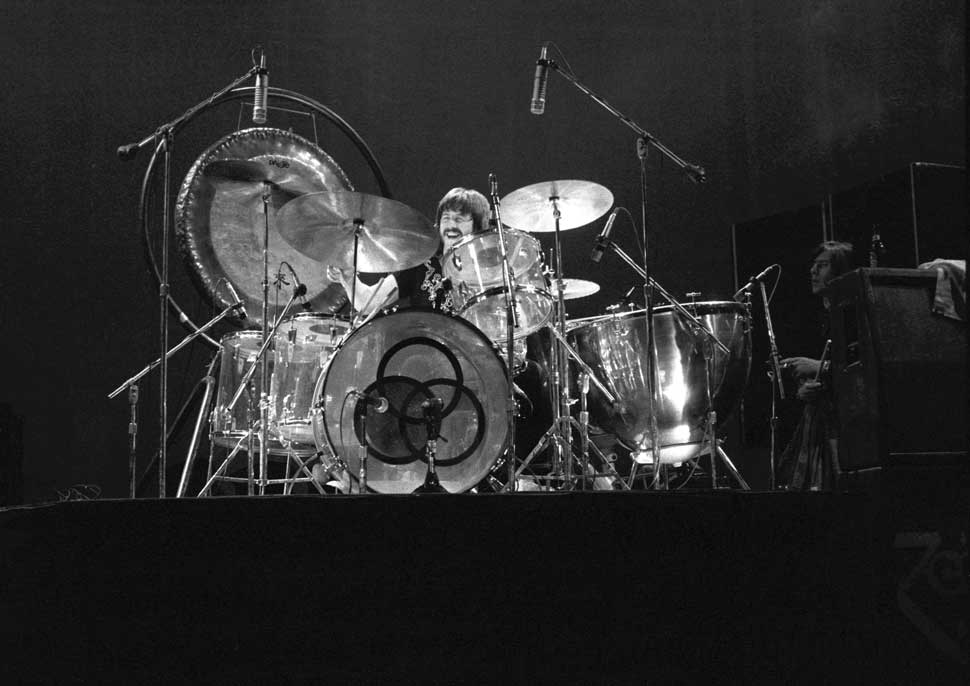

With Bonham on board, the New Yardbirds, as they were still called, played their first gig, in Copenhagen on September 14, 1968. The way in which Bonham had galvanised the band on those early gigs had a lasting influence throughout the recording career of Led Zeppelin (as they had now become). His dynamic playing perfectly suited such arrangements as Communication Breakdown, Stairway To Heaven, Kashmir, Achilles’ Last Stand and Trampled Underfoot, while his thunderous backbeat on When The Levee Breaks influenced a new generation of drummers.

Meanwhile the flow of hit albums and sold-out concerts for Zeppelin meant that his world changed virtually overnight. The once poverty-stricken Bonhams could afford flash cars, a big house and a champagne lifestyle. But he still had to work for a living. Out on the road, the 21-year-old Bonzo delivered a 20-minute, blood-spattered drum solo every night. And being the powerhouse of the energy-sapping Zeppelin show left him on the verge of collapse. He hated flying, which made him physically sick.

Holed up in hotels, the only way for a travelling musician to immunise himself against the routine was to take a drink or two, and perhaps experiment with drugs. Right from his teenage years, Bonham had enjoyed a beer. But he got boisterous after a few pints, which led to his reputation for mayhem. His pranks soon rivalled those of Keith Moon for outrage and destruction. Anyone getting too close found their clothes ripped and sprayed with lager.

Back home, Bonham returned to normality, and raised son Jason and daughter Zoë. He busied himself running his farm and breeding Hereford cattle in the calm peacefulness of the Worcestershire countryside. The real John Bonham preferred the bricklaying and decorating he’d learned from working with his father to carousing in California. Yet he also harboured a love of danger – epitomised by driving his drag-racing car at 240mph in Zeppelin’s movie The Song Remains The Same and his evident pride at son Jason’s performances for the Kawasaki Schoolboy motocross team.

Despite all the bravado, he confided to friends that he suffered from panic attacks before every concert. “I’ve got worse,” he said in 1975. “I have terribly bad nerves all the time. Once we start into Rock And Roll I’m fine. It’s worse at festivals. You might have to sit around for a whole day, and you daren’t drink because you’ll get tired and blow the gig. So you sit drinking tea in a caravan with everybody saying: ‘Far out, man.’”

After earning a fortune, Zeppelin became tax exiles, which meant living abroad. Then came a series of mishaps that dogged the group and undermined the drummer’s confidence still further. Bonham’s boisterous good humour began to give way to dark brooding and fits of anger.

Surrounded by hired security men, he may have felt invulnerable. But he overstepped the mark when he joined Peter Grant, tour manager Richard Cole and crew member John Bindon in a vicious assault on an American security guard at the fateful concert at Oakland Coliseum, California, in July 1977. Afterwards Bonham, Grant and the two Zeppelin henchmen were arrested.

Later it led to fines and suspended sentences – and to Led Zeppelin never returning to America after this tour.

It was all turning sour. Then came the death of Robert Plant’s son back in England. Suddenly it seemed like the group were close to breaking up. Bonham was left with more time on his hands, and his behaviour became unpredictable. Said his friend, drummer Bev Bevan of ELO: “He was an extrovert, a friendly, huggable bloke. But unfortunately the drink just got too much for him. He overdid it and could become quite aggressive. He was similar to Keith Moon. They felt they had to live up to their reputations.”

When Led Zeppelin played Knebworth in 1979, Bonham played well enough on the two landmark UK shows. But while on a German tour he began to exhibit signs of fatigue. At a show in Nuremberg, after three numbers he was taken ill. He then appeared unwell for the rest of the tour.

In September 1980, rehearsals for the scheduled North American tour were about to start at Jimmy Page’s home in Windsor. On the way there in a car with Robert Plant on the morning of the 24th John suddenly said: “I’ve had it with playing drums. Everybody plays better than me. I’ll tell you what, when we get to the rehearsal, you play the drums and I’ll sing.”

That day at Page’s house John started drinking at lunchtime and carried on until midnight. He allegedly got through 40 measures of vodka during a marathon 12-hour session. After falling asleep on a sofa he was put to bed by his assistant and laid on pillows for support.

The following morning there was no sign of him. John Paul Jones and road manager Benje LeFevre found him apparently unconscious. They tried to wake him, then realised he was dead. Everyone was saddened, and even angry, at the waste of life. Peter Grant went into a depression that lasted several years.

Rumours suggested Bonzo had been taking drugs, but it was drink that had caused his death. Said John Paul Jones: “It was just at the point where we had all come back together again. We had high hopes it was all coming right. Bonzo had been getting a bit erratic and he wasn’t in good shape. There were some good moments, but then he started on the vodka. I think he had been drinking because there were some problems in his personal life. But he died because of an accident. He was lying down the wrong way.”

John’s death left the Bonham family devastated.

“It didn’t take long to work out when I arrived, because security guards stood at either side of the gate and Robert Plant was waiting for me,” revealed John’s younger brother, the late Michael Bonham, of how the news was broken to him. “He told me to leave my car and walk up the drive with him. As he did so, he gently broke the news to me that John had died some time during the previous night. I don’t know enough words to describe the impact his words had on me in that split second. But as I sat with my family the only thing I knew was that the brother I loved so much, my lifelong hero, was gone.”

It was revealed at the inquest that he died from inhalation of vomit during his sleep, ‘due to consumption of alcohol’. The verdict was accidental death.

The funeral took place at Rushock Parish Church in Worcestershire on October 10, 1980, attended by mourners including family, friends and his bandmates. Tributes poured in from stars such as Paul McCartney, Phil Collins, Cozy Powell and Carl Palmer.

Said Bev Bevan: “The funeral was the most traumatic I had ever been to, because he was so young and had so much in front of him. His family were utterly distraught. Who knows what more he would have done as a drummer?”

Led Zeppelin could have carried on with another drummer, as The Who had done after the death of Keith Moon, but realistically no one could replace him. Led Zeppelin had officially broken up. Other drummers, including Phil Collins and Jason Bonham, have played on Zeppelin ‘reunions’ since. None could hope to match the power, magic and presence of the much-loved man who once told Robert Plant he was the greatest drummer in the world.

“He was definitely the greatest rock’n’roll drummer that ever lived,” Jimmy Page once said. “And that’s all there is to it, really.”

Additional information from Late Nights, Hard Fights: My Brother John by Michael Bonham and Jerry Ewing. This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock's Led Zeppelin Special, published in 2005.