For Dawoud Bey, history is anything but dead. Through the Hyde Park photographer’s eyes and his lens, the events of the past are very much alive and tangled amid contemporary life.

A MacArthur fellow whose intimate, evocative portraits have been the subject of major exhibitions across the country, Bey has shifted his focus in the last few years to the indelible mark people have had on place and space, and in particular, how the legacy of slavery still lives.

Bey, 70, began this exploration in 2017 with his series “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” a set of large-scale black-and-white images that features purported stops on the Underground Railroad in Ohio.

“That work was about trying to visualize and imagine the landscape of fugitive activity,” Bey says. “How Black bodies moved across northeastern Ohio in an act of self-liberation to get themselves to the other side of Lake Erie and Canada.”

From there, the Columbia College Chicago professor stepped further back in time and turned his camera to the places from which Black slaves escaped — the west banks of the Mississippi River in Louisiana, where more than 350 plantations once stood. This set of images, which Bey titled “In This Here Place,” focuses on Evergreen plantation, a well-preserved sugar cane plantation and historic landmark about 45 miles upriver from New Orleans.

Now, Bey has completed the three-part work with his new photo series titled “Stony the Road,” on display in Richmond, Virginia, where African men and women once were sold into slavery. The series is part of the exhibition “Dawoud Bey: Elegy” at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts that for the first time brings together the three projects.

“Virginia was an epicenter for the import and export of Black bodies,” Bey says. “This is where this whole narrative basically begins, where 350,000 enslaved Africans walked into slavery.”

Along with the exhibition, which runs through February, Bey has published a book. On the pages of “Elegy,” the 42 images create a haunting catalog of the American landscape. They illustrate, Bey says, how history reverberates in the present, how it doesn’t disappear.

Below, Bey shares the stories behind some of the “Elegy” photographs suspended somewhere between the past and present.

‘Irrigation Ditch’

“This is Evergreen, which still has an active sugar cane business on that landscape. This is a view of that, but the picture itself is meant to pull you in and suggest the vastness of this landscape. That it goes on for as far as the eye can see. I’d never been on a plantation landscape before. I still haven’t seen a cotton field. Being in those sugar cane fields and seeing the absolute enormity, even of a reduced sugar cane operation, it really gives you a sense of the intensely grueling labor needed to harvest sugar cane.”

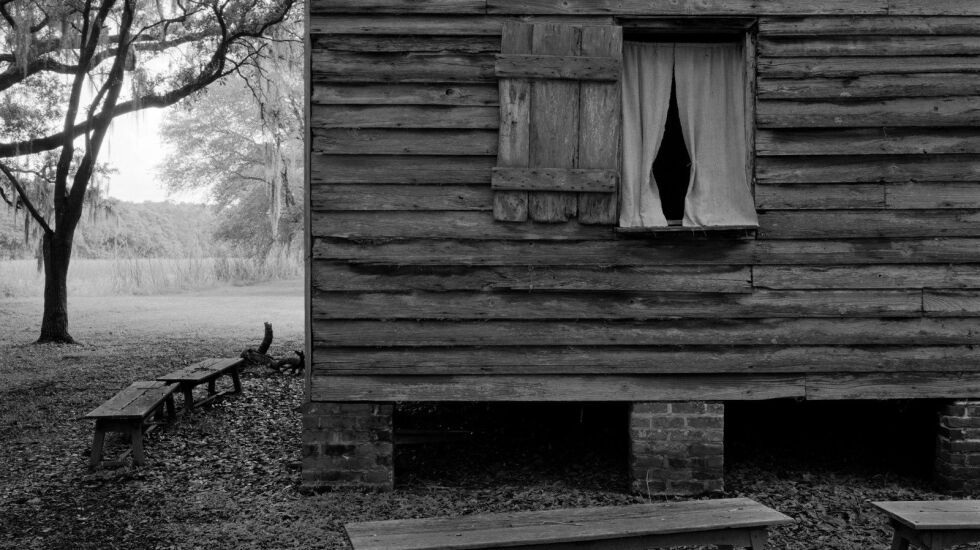

‘Cabin and Benches’

“This slave cabin is from Evergreen plantation and is one of the 22 intact cabins that remain on the site. One of the reasons they’re so well-preserved is that they were occupied until as recently as 1947 by people who were the descendants of the enslaved. People who lived here as sharecroppers on the same land where their family had once been slaves. They lived here with no running water. No bathroom facilities. This cabin looks like someone just got up and walked away from the scene. There are benches still there. Even the parted curtain, it has a very haunted and haunting feeling to it.”

‘Conjoined Trees and Field’

“There is something deeply human about these touching trees on this plantation landscape. It’s one of the few pictures that seems deeply allegorical in some way. These two touching trees and this once-horrific landscape. It’s the persistence touch and the persistence of connection, as suggested by trees, which are very much a living thing, too.”

‘Untitled #1 (Picket Fence and Farmhouse)’

“I found this house from doing research on Underground Railroad safehouses in Cleveland. The site was not overly modernized, and there’s the white picket fence, which is significant within the sociocultural sensibility of this country. The white picket fence signifies a kind of property demarcation. The very real aspiration to get your own house, around which you can put a white picket fence to mark your space.”

“I very much want to keep working in the landscape tradition,” Bey says. “For me, the human presence in these photographs hasn’t completely disappeared because it shapes how I make the photograph. They’re always eye-level.

“I’m not doing interesting and unusual things with the camera to make interesting pictures. Even if the photographs look down, they’re looking down from a human vantage point.

“They are meant to suggest the human presence in that place. I actually see it as people, those Black presences, moving from in front of the camera to behind it.”