David Harbour denies he’s become British. And yet… the evidence is stacking up. Firstly, the Stranger Things star begins our interview by making a cup of tea. Also, he’s married to London’s own Lily Allen. And now, he’s about to spend his summer treading the boards of the West End. “I am so not British,” he tells me, before doing an exaggerated, twangy voice: “I talk real cowboy in the house.”

Talking to me over Zoom from his home in Brooklyn, he’ll concede on one matter only. “The one thing that I will say about your island, that I love more than anything in America, is” – and this he says as though it’s a new phrase he’s testing out – “the Sunday roast idea. We have something in America called Thanksgiving. You have it every Sunday. And I was BLOWN away. Lily made a roast early on when we were dating and I was like, ‘What the f*** is this?’ She’s like, ‘this is a roast’. I was like… ‘this is Thanksgiving!?’”

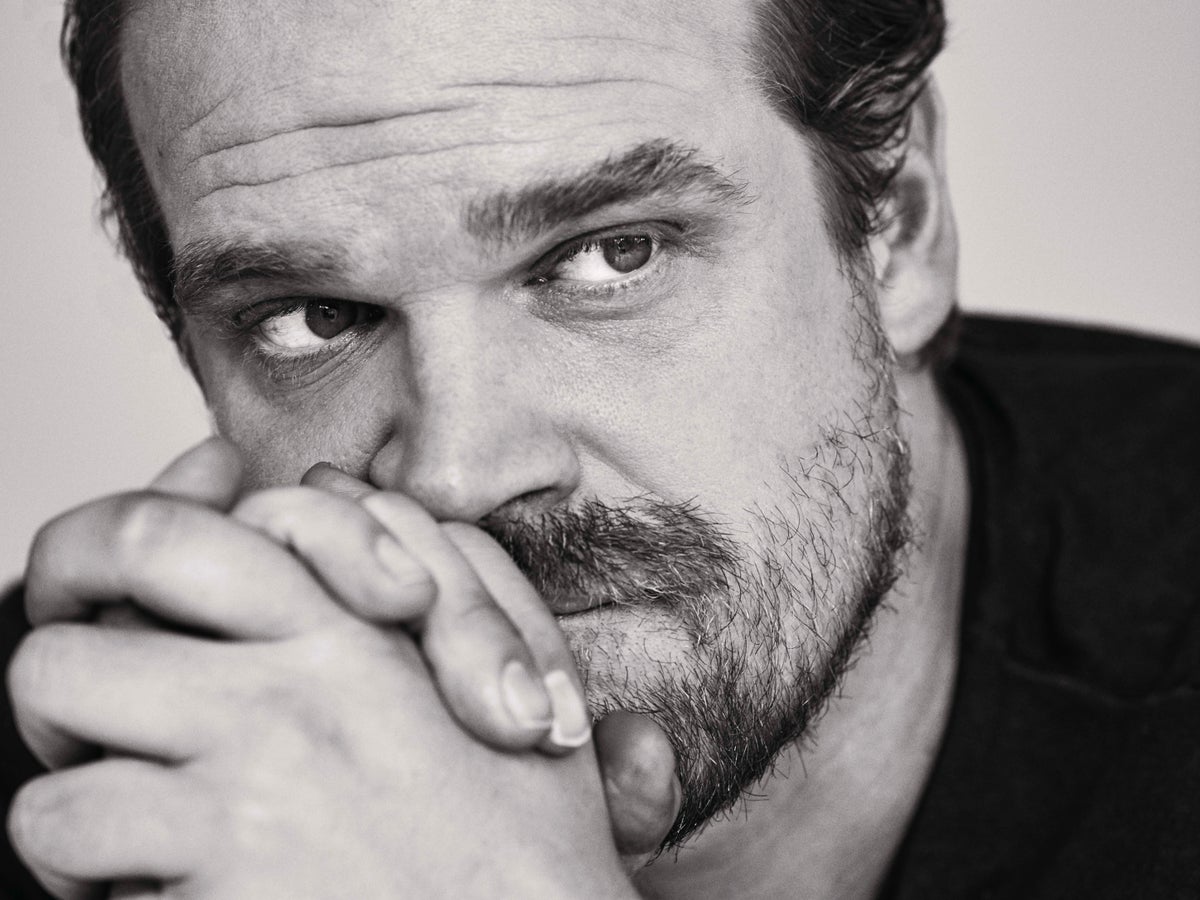

Am I a bit sad that we can’t claim him as one of our own? Maybe, but the UK does at least get him for the summer. Besides, long-term adoption would probably never work. Harbour is resolutely his own guy: emphatic and unreserved in conversation. When he’s serious about something he sits forward, his face close to the camera; when he laughs, he leans away, throwing his head back with a roar. A narrative has already formed around the idea of him as an “overnight success” in his forties, a late bloomer who hit the big time playing police chief Jim Hopper in Netflix’s Stranger Things. The world took the character to their hearts, this broken, lonely curmudgeon with the deceptively sweet soul. But talk to Harbour, and, delighted as he may be by life’s turn of events, he’d define “success” a little differently. Blockbusters might seem to be his stock and trade – he’s been in Bond and Black Widow – but really, he’s an old-school thesp. His early career was full of Shakespeare and Stoppard, and he won an early big-screen role in Revolutionary Road after Sam Mendes watched his Tony-nominated performance in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?.

Now he’s returning to the stage for Theresa Rebeck’s Mad House, playing a role written especially for him. The pair had got talking at the theatre once. Harbour liked Rebeck’s writing; he was amused by the way she complimented his acting. She’d told him: “I really like when you’re loud. You’re such a big guy, when you scream it gets me so excited.” He wanted to use his newfound success to amplify certain voices, be “in control of the stories I want to tell” – so he asked Rebeck to write a play for him.

“I’ve had some issues with, you know, madness – or what society deems ‘mental illness’,” Harbour tells me. (He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the age of 26 and spent time in a mental health facility.) “So I told her stories about my situation, she told me stories about hers, and she went off and wrote this beautiful play about a kid who’s taking care of his dying father, and that kid has been in a mental asylum, and the rest of the family don’t really trust him.” Harbour plays the son, Bill Pullman his father.

Mad House demands “a solid two hours 45 minutes of, like, relentless verbiage, experience, emotion, behaviour”. The work is intense. But – serious, sitting forward – Harbour says this is where he’s supposed to be. “I feel liberated. I feel like my mind is light. It’s something I was born to do,” he says, his voice soft. “Like, I really wasn’t born to be a film and TV guy. I’m a theatre animal. I’ve been doing this since I was a kid, and I really just sort of… come alive on stage, my whole body. It’s one of the only places where I feel I can truly live.”

Strangely, if Harbour really were British – if someone was saying this to me in a British accent – I’d think they were just being a luvvie. But I buy it from Harbour. Theatre has been like therapy for him, a place where he can follow the impulses that he’s had to learn to moderate in real life. “The idea that you can allow yourself that freedom is something that I feel like, first of all, mad people have. The psychotic brain is very much like the reptilian brain, just responding to impulses. But it’s also something that as a theatre person, or an actor in general, because I can hide behind a mask, I’m allowed to like… throw it all out there,” he explains.

I never really cared that much about success. I cared more about being great— David Harbour

It’s seven years since Harbour was on stage. A lot has changed for him. Back then, he was single, not taking care of himself. He was earning $250 (£200) a week – nothing like a living wage for New York – and keeping his overheads so low that he didn’t even have a cell phone. He did it because the work mattered to him. “I think, even if I could make no money or headway in this industry, I’d still be doing community theatre. It’s always been about pure expression for me,” he says. “I never really cared that much about success. I cared more about, like, being great. I think the two are different.” He describes friends who are living in the East Village, doing off-Broadway theatre as ‘great’. “They’re not successful in a certain economic way. But they’re still some of my favourite actors in the world.”

Hmm. No interest in money or success, a fastidious commitment to community theatre. Not what you’d expect from a guy who has been in his fair share of superhero films. What does he make of the idea that Marvel is wrecking cinema? Back he leans; out comes the booming laugh. “I don’t see it as anything but entertaining, fun stuff,” he says. Still, he wishes there was “broader scope” in the film world. “When I was growing up, Goodfellas came out in the cinema, and it was like… the Captain America of its day. We all rushed out to see it. And I don’t know if those movies really can exist in this climate anymore,” he says. That Marvel has been able to become such a dominant brand, he suggests, is “a smaller piece in a much larger cultural puzzle”.

His role as moustachioed, naughty CIA dude Gregg Beam, in 2008 Bond film Quantum of Solace, now “feels such a random thing that happened”. Harbour has two bets on who the next Bond should be: himself. Or Lily Allen. He saw No Time to Die and admired the way that the character, usually trapped in time, was allowed to develop. “The problem with James Bond is he’s always going to be, I don’t know, 35 and kind of sexy. So, what do you do with James Bond when you start to become… you know, you’re a human. So I like that they gave him the respect. He, apart from Sean Connery, became the quintessential Bond for our generation, and giving him the respect of ‘let’s just kill him’ was kind of interesting.”

It was an instance of a brand taking a risk, throwing a hand grenade into more than half a century of fans’ expectations. It’s a tricky balance to strike, something that Harbour is all too conscious of when the Stranger Things machine boots up again. It’s “stressful”, he says with a laugh. Season four is now out in the world. When they first began this offbeat, neon-badged show about outsiders, he didn’t think anyone would watch it. Now it has a global fanbase. He believes it’s remained true to its essence – but people will have their own thoughts. “This is always an interesting time, to see if the audience can give us that leeway, or if they reject it.”

He’s always trying to mentor younger castmates Millie Bobby Brown and co, who have come of age under the spotlight. “They are involved in something that is a minefield. The popularity and the money that they’re dealing with at 12 and 13 years old is… it just makes you an adult. They don’t really get to have the childhood that I wish they could.”

But there’s another reason why the youth of today are on his mind. Throughout our conversation, Harbour talks about the adjustments he’s made to his life because now he has kids. After marrying Allen in 2020, he’s now stepfather to her daughters Marnie, 9, and Ethel, 10, who “came as part of the package”. He goes a bit gooey whenever he mentions them.

“It was lucky for me because I am now in a relationship with three women. Very strong-minded women,” he jokes, underlining each word. It’s a responsibility he takes seriously – relishes, even. “[It] has brought a whole new depth to my life that I never had before. Made me an entirely new man. And that’s wonderful.”

I was excited to see Harbour’s alarmingly chic apartment, which he showed off in a viral Architectural Digest video – but he’s moved out. That was from his “bachelor days”. He and Allen are currently renting while they design a new place, which they’re keen to show off at some point. “I thought I was quite the master of it. Then you marry Lily Allen, and you realise that you’re a chump compared to her design tastes.”

Interior design might be where the artistic collabs end. Allen nabbed an Olivier nomination earlier this year for her stage debut in 2:22 A Ghost Story , and while acting together is something they’ve discussed, Harbour insists that it would “have to be pretty specific”.

“The energy we have in our home life is really nice, and to bring in draaaa-ma… Generally, I like to maintain pretty firm boundaries around people that I work with, because I like to be able to be as impulsive and spontaneous and provocative as I can when I work,” he says. “I like when someone hurts my feelings on stage – like, genuinely hurts my feelings. And if I maintain those boundaries with someone, we don’t have to worry about being friends, or, y’know, lovers outside. We can just come together and like, really throw down and work. And so I don’t know how I would do that with Lily. We’d have to really figure that out.”

He may not be British. But he really is an old-school thesp.

‘Mad House’ is at the Ambassadors Theatre until 4 September