“What the hell is wrong with freedom, man? That’s what it’s all about,” asserted Billy, Dennis Hopper’s wide-eyed, mononymous antihero in search of America during a memorable scene in the groundbreaking 1969 road movie Easy Rider.

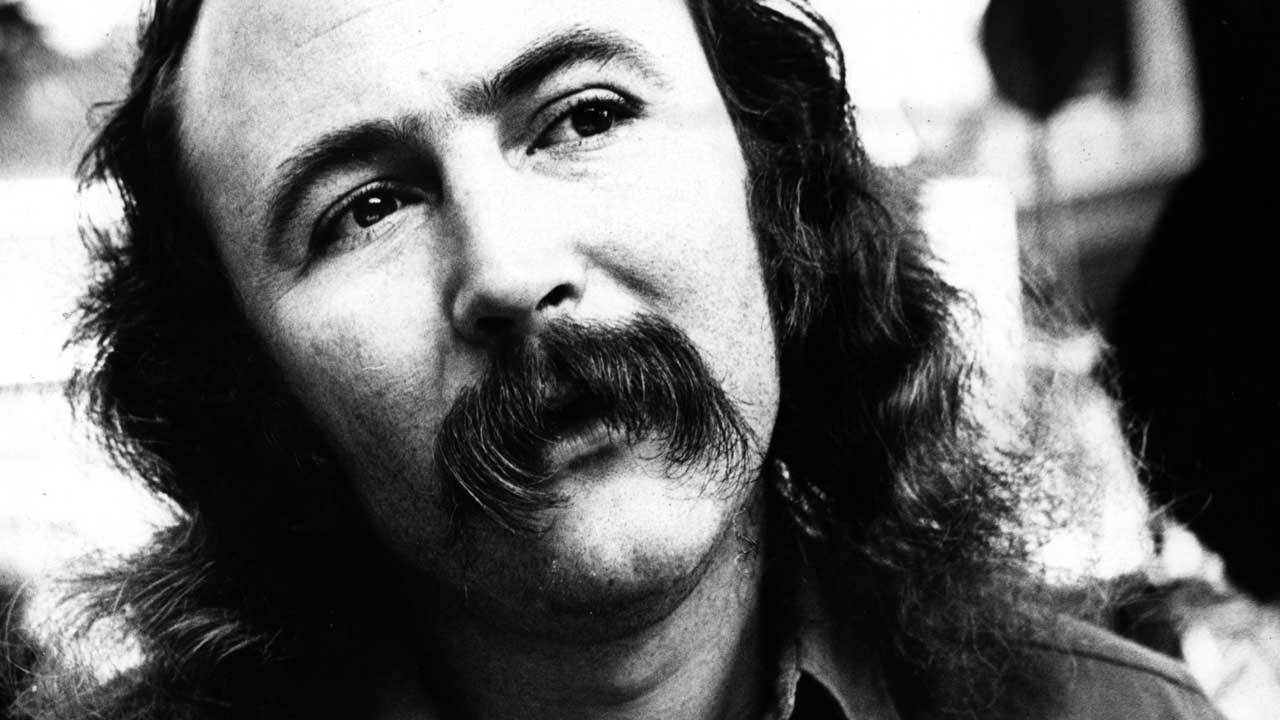

Billy – along with Wyatt, his travelling companion, played by Peter Fonda – represents the hedonistic and rebellious cult of youth, endeavouring to survive in a straight and intolerant society. That Hopper, also the film’s director, chose to model his adventuring and idealistic character – complete with a drooping walrus moustache, shoulder-length hair and fringed jacket – on David Crosby was testament to the pervading influence the free-spirited countercultural icon held on a generation atthe tail end of that revolutionary decade.

When Easy Rider was released in July that year, Crosby, Stills & Nash, the self-titled debut album from the supergroup trio who would spearhead the gilded Californian scene that would dominate the early 70s, were only two months old, but already the band’s co-founder David Crosby (looking every bit the happily stoned blueprint for Billy on the album’s cover) was considered an outspoken, anti-authoritarian, puckish prince of the hippie era.

It was a role in which Crosby thrived, where an imperial appetite for sex, drugs, and rock’n’roll wasfulfilled beyond excess alongside a nagging predilection for contention – through the years, the brunt of his raw distemper would be especially felt by politicians, lesser pop stars and, most notably, his own bandmates. But it was his voice – that rich, mellifluous, gliding expression of his soul – that truly set him apart, endeared him to the world’s greatest talents, and endured to the very end.

By the time of his death, aged 81, on January 18, 2023, Croz – as he was affectionately known – was an elder statesman of music, a Grammy Award-winning, two-time inductee into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame (as part of The Byrds and CSN), whose twilight streak of wonderful solo albums more than made up for the wilderness years that preceded them. He was a quick-witted, acid-tongued Twitter raconteur, attracting new followers across generations with his honest assessments of their joint-rolling skills.

His artistic revival, however, was not without its share of personal torment. Beset with health and financial hardships stemming from the depths of his addictions, the mercurial Croz died estranged from the peers with whom he created his greatest works. His freedom, it seemed, had come at a price.

Roger McGuinn was wary of Crosby from the moment their professional paths chanced to meet. A folk guitarist formerly of the Chad Mitchell Trio who had rocked the Greenwich Village scene by infusing traditional ballads with a Beatles beat, McGuinn had moved to Los Angeles and hooked up with Gene Clark, fresh from his stint in the New Christy Minstrels, to forge this new folk-rock vision as a duo, but quickly realised the similar tone of their voices meant a third singer would be required, and actively began looking for a new member. They found him at the Troubadour club in West Hollywood in early 1964.

“This guy is on stage who comes on very arrogant and kind of like puts the audience down,” Clark recalled in Crosby’s 1989 autobiography Long Time Gone. “I said: ‘Who is this guy?’ Roger said: ‘I know him.’ He didn’t want to talk about it. Then the guy sang and I was just blown away. I said: ‘Man, is he good! That’s it. You can’t ask for any better than that.’ McGuinn said: ‘No, man. I know David.We tried to work together. It’s impossible. It’ll never work.’”

Crosby had harboured his own folk aspirations, launching his performing career in Santa Barbara as a duo with his elder brother, Ethan, before striking out alone for New York, where he would first encounter McGuinn. Back in his native LA, Crosby approached McGuinn and Clark with the proposal of joining them, adding the sweetener that his friend Jim Dickson had a recording studio they could use. It was an offer McGuinn couldn’t refuse.

In the months that followed, the group, under Dickson’s management, were enhanced by the addition of Chris Hillman on bass and Michael Clarke on drums, and their new collective moniker: The Byrds. Their scrappy conception was played out on the stages of California clubs, indebted to the insolent, long-haired impact of the Rolling Stones, until a breakthrough came in the form of their debut single, released in April 1965: a jangly, electrified take on Bob Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man.

Suddenly The Byrds were a phenomenon. Their chiming brand of folk rock swept the airwaves as America fought back against the British Invasion. The Mr. Tambourine Man album, dominated by Dylan covers and Gene Clark originals, established the group as pioneers of the emerging West Coast sound, which in turn would surface in the strains of The Beatles’ Rubber Soul.

McGuinn may have taken the lion’s share of lead vocals, but standing in the group’s front line brandishing honeyed harmonies through a beatific smile, Crosby was a radiant star-in-waiting. “That was when we started making money,” he recalled. “Then I bought a new green Porsche. That’s when I started realising that the sixties were going to be interesting times.”

A life in the spotlight wasn’t such a far-fetched prospect for Crosby. His parents, both of whom were from an upper-class New York society background (his mother, Aliph Van Cortlandt Whitehead, was a descendent of the politically prominent Van Cortlandt dynasty), had moved to Los Angeles to follow the cinematographic ambitions of his father, Floyd Crosby – a decision validated by his Academy Award for cinematography in 1931. Ethan, born in 1937, was followed four years later by David, who would grow up on the Hollywood sets his father shot on. “I was always a showbiz kid,” Croz later conceded.

Music was a binding force in the Crosby household, where the family would regularly gather in song, with Floyd on mandolin, Ethan on guitar, Aliph singing and David providing his first harmonies. But even these communal performances did little to tether the increasingly provocative behaviour that saw a teenage David ejected from a string of exclusive private schools, and was exacerbated after his parents split in the late 1950s. A new world was opened to David upon being taught a few chords on guitar by his brother, and seeing what delights the local jazz clubs, at which Ethan played, had on offer.

“I’ve always said that I picked up the guitar as a shortcut to sex,” Croz wrote. And, sure enough, the budding folkie pursued girls with a vengeance, until his promiscuous proclivities landed him in hot water. Learning that he’d got a girlfriend pregnant, Croz left California, and embarked on the musical journey that would eventually lead to his fateful union with McGuinn and Clark.

The Byrds were restlessly creative, keenly exploring different musical avenues in their first few glorious years to wondrous effect. Folk rock gave way to jazz, country and Indian influences, producing the earliest traces of what would become psychedelia. Songs like Eight Miles High, Mr. Spaceman, and 5D (Fifth Dimension) demonstrated the group’s remarkably progressive nature in their sonic expanse.

After chief songwriter Clark quit in February 1966, it allowed the other Byrds to flourish as composers. Crosby would collaborate with McGuinn to write stellar tracks such as the be-bop raga I See You on that year’s Fifth Dimension album, and the wistful Summer of Love anthem Renaissance Fair on 1967’s Younger Than Yesterday, but his own works proved a keener insight into his creative development, where enigmatic lyrics, atypical tunings and free rhythms reflected his penchant for pushing boundaries.

Everybody’s Been Burned is the hauntingly beautiful closer to the first side of Younger Than Yesterday, while Mind Gardens evoked the ruminations of an acid trip. Crosby’s songs were innovative, interesting and profound, and gave him the confidence to wrestle for creative control of The Byrds, a power struggle that would falter against the steadfast McGuinn and Hillman, who would often rebuff his material.

“I wasn’t real happy about my role in the group,” Crosby wrote of this time. “I was starting to write good songs. I had written a couple of things that made me proud and nothing was happening with them… I had a large ego and Roger and I started having conflicts with each other over material, business, expenses… everything we did was a potential source of disagreement.”

Crosby was fired from The Byrds in October 1967. Their arguments over songs had come to a head (the group particularly disliked his Triad, a song about a three-way relationship), while Crosby’s rant about his JFK conspiracy theory at that summer’s Monterey Pop Festival hadn’t helped matters. “It hurt like hell,” Croz would later admit.

Around this time, Croz met Joni Mitchell and, astounded by her abilities, offered to produce her debut album, Song To A Seagull. “David was wonderful company and a great appreciator,” Mitchell said in Long Time Gone. “When it comes to expressing infectious enthusiasm, he is probably the most capable person I know. His eyes were like star sapphires to me. When he laughed they seemed to twinkle like no one else’s…” The pair were romantically involved for a short while, but Crosby remained an active supporter and patron of Mitchell for the rest of his life.

It was, in fact, in Mitchell’s Laurel Canyon kitchen that the next chapter of Crosby’s career was born. He’d been meeting regularly to jam with friend Stephen Stills, whose band Buffalo Springfield had imploded in the spring of 1968. One day that July, the pair were visiting Mitchell when her new boyfriend Graham Nash arrived. Nash was the guitarist and a vocalist with English pop group The Hollies, and though the three had previously met in passing, this was the first time they’d formally shared company.

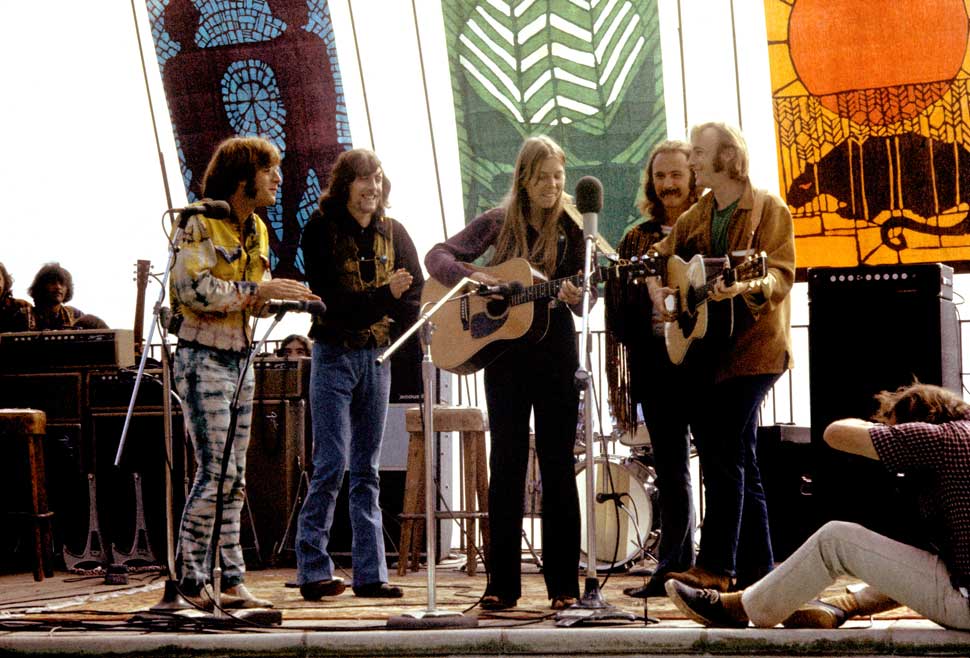

Soon, Crosby and Stills were previewing the duet they’d practised for Stills’s new song You Don’t Have To Cry. An impressed Nash asked them to play it a second time, and then again, only this time he joined in, adding a third, soaring layer to their weaving vocal harmonies. The resulting sound was, to all present, immediately epiphanic. “We knew what we were going to be doing for the next few years, right there,” Croz recalled in the 2019 documentary David Crosby: Remember My Name, when he revisited the historic house.

Once Nash had broken free of The Hollies, Crosby, Stills & Nash was officially born. Their democratic choice of band name was a reaction to the artistically stifling confines each had felt in their former groups. “The whole idea of starting the group in the first place,” Croz explained in his documentary, “was to build a mothership group that would allow us the freedom to do what we wanted to do.”

CSN duly signed to Atlantic Records, and their self-titled debut album was released in May 1969. It arrived at the perfect time; the previous year Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding and The Band’s Music From Big Pink had signalled a sea change that washed away the pretences of psychedelia and inflated blues rock in favour of a pastoral, acoustic sound that allowed for more introspection – CSN’s sumptuous, intricate melodies and mellow contemplations were to prove irresistible in this climate.

On the album, the romantically poetic Guinnevere was Crosby’s, as was Long Time Gone, an emphatic response to Robert Kennedy’s assassination. Wooden Ships, a co-write with Stills and Jefferson Airplane’s Paul Kantner, was born in the chilling shadow of the Vietnam War. These songs, and the remainder of Crosby, Stills & Nash, propelled the album into the US Top 10, sparking a thrilling and influential 70s success story that would be plagued by simmering tensions.

Neil Young, ex-guitarist with Buffalo Springfield, was brought into the fold that summer to alleviate former bandmate Stills’s multi-instrument duties, and in August the new quartet played their second gig, at the Woodstock festival. Work had begun on CSNY’s first album, Dêjà Vu, when Crosby’s life was upturned by tragedy.

On September 30, Christine Hinton, Croz’s 21-year-old girlfriend and the subject of Guinnevere, died in a car crash. He was summoned to the hospital to identify her body. “He was never the same again,” Nash once disclosed. Croz would later acknowledge that that horrifying experience and the ensuing grief sent him spiralling into depression and a dependency on hard drugs to numb the pain that would take years to conquer.

“I got involved in [heroin] because I was in a great deal of pain emotionally and it seems to help you through that,” Croz told Classic Rock in 2006. “What it actually does is stuff it. And stuffing emotional trauma doesn’t deal with it at all, it just festers. Which is what happened.“

Dêjà Vu was an unquestionable smash hit. Released in March 1970, despite the incessant internal wrangling that threatened to derail sessions, and the dark mood that permeated the music, it was certified Gold in just two weeks. With Almost Cut My Hair, Croz sealed his reputation as the consummate hippie, unfurling his ‘freak flag’ in typical defiance.

Their supergroup status confirmed, CSNY reigned at the dawn of the new decade and reaped the rewards. But even millions of dollars couldn’t abate the ego clashes that exploded within the group, and in early 1971 they went on hiatus. It was to be the first of many break-ups in their 40-year saga.

From their reconciliation in 1973 to their final, inexorable split around 2016, the members of CSNY played in every configuration and to various degrees of success (Crosby and Nash enjoyed regular collaborations). Neil Young effectively severed ties with Crosby in 2014 after Croz made disparaging remarks about Young’s wife, Daryl Hannah. In 2016, even an exasperated Nash followed suit. But in spite of all their differences, all members remained open to the possibility that one day they might reunite for the sake of music. Crosby’s death means that will now never happen.

Away from the volatile culture of CSNY, in early 1971 Croz initiated an autonomous solo career with the release of If Only I Could Remember My Name. The album’s sessions were musical therapy for a mourning Croz, where his songs and improvisations were embellished with the reassuring support of friends including Nash, Young, Paul Kantner, Joni Mitchell, and the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, who played a considerable and consolatory role in its creation.

The lush, kaleidoscopic qualities of songs like Laughing, Song With No Words and I’d Swear There Was Somebody There made for an enchanting, ethereal aural experience, but it certainly wasn’t commercial, and the album practically disappeared after a critical mauling.

By the turn of the new millennium, however, as Devendra Banhart and Joanna Newsom’s idiosyncratic stylings heralded the ‘New Weird America’ tag, If Only… underwent a reappraisal that rightly saw it exalted to cult status, and is now considered Crosby’s masterpiece. Nevertheless, after its initial release it would be 18 years before Croz would get his shit together again and record another album under his own name.

Drugs were the root of Crosby’s downward trajectory. Heroin had been supplemented by a devastating addiction to crack cocaine, which consumed his thoughts and finances in the early 80s, rendering him useless to his band. “I let those guys down terribly when I became a junkie,” he said. “I went right down the tubes in front of them, and they watched their band go all to shit because I couldn’t pull my weight.”

After a number of arrests on drugs and firearms charges, and repeated desertions from rehab programmes arranged by what friends were left supporting him, Croz’s nadir came in 1986 when an unsuccessful appeal for an earlier conviction led to five months in a Texas prison. “A horrible place,” Croz told Classic Rock. “People die there. Every day… It was a helluva place to try and kick cocaine and heroin at the same time, which is what happened.”

Croz cleaned up, and in 1987 married girlfriend Jan Dance, herself emerging from her own drug ordeal. The marriage lasted until his death, and produced a son, Django, in 1995. Later that decade Crosby fathered (via sperm donation) two children for Melissa Etheridge and her then partner Julie Cypher. But there were traumas to come.

Croz was indebted to the Internal Revenue Service, and the impact of drugs on his health was serious. In 1994 he was diagnosed with hepatitis C, and underwent a liver transplant. Ten years later he developed type 2 diabetes. Soon after, he was in hospital for major cardiac surgery. In 2020 he lost one of Etheridge’s children, Beckett, who was just 21 and had been struggling with opioid addiction.

Musically, though, Croz was back on track. Aside from the ongoing CSN activity (American Dream and Live It Up were released in ’88 and ’90 respectively), he had renewed his solo work, returning with the middling Oh Yes I Can in 1989. In the early 90s, James Raymond entered Crosby’s life. Raymond, the son of the girlfriend he had abandoned in 1961, had inherited his father’s musical inclinations, and the pair began a fruitful and symbiotic working relationship together. “He’s a better musician than I am – by a considerable amount,” Croz told Classic Rock. “He came to me in such a generous and kind way. And has been such a good friend to me.”

Father and son joined guitarist Jeff Pevar in a new group, CPR. Although they disbanded in 2004, Raymond remained Crosby’s musical director and closest collaborator henceforth. He wrote more than half and played on all of Croz, the respectable 2014 album that kick-started a creative streak in Crosby, which produced a run of acclaimed albums.

The excellent Lighthouse in 2016 teamed Croz with fusion instrumentalists Snarky Puppy’s Michael League who, in his role as producer, brought in vocalists Becca Stevens and Michelle Willis. So impressed was he by their combined talents, Croz incorporated them as The Lighthouse Band, who became his touring unit, and in 2018 played equal parts in delivering the celebrated Here If You Listen, on which their shimmering harmonies and exquisite musicianship were demonstrated to such magical effect.

It was later that year that this writer had the pleasure of meeting Croz in person, interviewing him backstage before a show in London. He had such a benign presence – a charming Buddha-like sage on the venue’s leather couch, sharing with me advice on parenthood and hard life lessons he’d learned from his tumultuous history. But behind his warm joviality I could detect a tangible sadness. His lack of earnings from record sales and no CSN income had put Croz in the resentful predicament of having to work for a living at 77.

His fortunes, which deteriorated further during the covid restrictions, were reversed in early 2021 when he sold the publishing rights of his catalogue, which saved him from ruin. It also allowed him to enjoy making music for pleasure again, and For Free, his eighth and, ultimately, last solo record, was released that July. It was, Classic Rock noted, “the sound of Crosby finally at ease with himself”.

When I spoke to Croz again, in November 2022 for Classic Rock, he was insistent that he would continue sending his music out into the world for as long as he was able, for that was his calling, his purpose. “It’s the one contribution I can make,” he enthused. “The one place I can make anything better, is to make all the music that I possibly can.”

David Crosby died, in the company of Jan and Django, of a “long illness”. His embattled body is at rest, but the many, marvellous songs he gifted will live on. The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson tweeted to say he was “heartbroken” by Croz’s passing, and scores of friends, contemporaries and celebrities were quick to follow in paying tribute.

A “deeply saddened” Stephen Stills eulogised Croz in a statement that, in touching on their often precarious relationship, revealed that they were “happy to be at peace” at the end. “He was without question a giant of a musician, and his harmonic sensibilities were nothing short of genius,” Stills said. “[I] shall miss him beyond measure.”

Similarly, Graham Nash was keen to focus on the positive aspects of their long-standing and testing friendship. “What has always mattered to David and me more than anything was the pure joy of the music we created together,” he posted. “David was fearless in life and music… He spoke his mind, his heart, and his passion through his beautiful music and leaves an incredible legacy. These are the things that matter most."