In December 2023, 34-year-old Dave Onawelo told staff in the hospital emergency department at Whipps Cross Hospital in east London that he was experiencing a sickle cell crisis. While waiting to be seen, his mother raised concerns that Onawelo’s condition was worsening, but was told by hospital staff that she was being anxious. Over the following hours, he became unresponsive and died.

In May 2022, alone in a prison cell on the healthcare unit at HMP Pentonville in north London, 43-year-old Wayne Bayley told prison officers that he could not breathe. Bayley did not receive medical assistance and died hours later.

Both men had sickle cell disease (SCD) and died from sickle cell crises. Their recent inquests have revealed that poor care contributed to both deaths. A “lack of compassion and clinical curiosity” was a factor in Onawelo’s death according to the coroner, and earlier treatment was “likely to have resulted in a non-fatal outcome”.

Bayley’s family described their struggle to ensure that his true cause of death was identified, after the cause was first reported as “unascertained”. The inquest ruled his death was caused by a sickle cell crisis, and that neglect from prison staff prevented his survival.

These are not the only inquests in 2024 that have identified problems in care for people experiencing sickle cell crises. Furthermore, the 2021 all-party parliamentary group’s No One’s Listening report showed that patients commonly experience poor hospital care during sickle cell crises. So, how can we make sense of these problems that SCD patients face?

What is a sickle cell crisis?

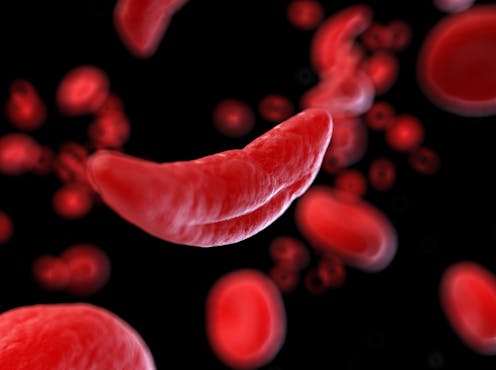

SCD is an inherited blood disorder which can affect every part of the body. In the UK, more than 17,000 people are currently living with it. While SCD occurs in people of all ethnic groups, most people with the disease in the UK are of Black African or Black Caribbean heritage.

Sickle cell crises are episodes of severe pain caused by sudden blockages of blood vessels by abnormal sickle-shaped red blood cells.

These crises can happen spontaneously, or they can be triggered by cold, dehydration, infection, stress or other factors. The suffering of a sickle cell crisis is powerfully depicted by the rapper A Star in his song Hidden Pain.

Crises are treated with pain relief and fluids. In some cases, oxygen, antibiotics or a blood transfusion are required. National guidelines require hospitals to provide pain relief to people in sickle cell crisis within 30 minutes of arrival. However, even when they describe severe pain, those in crisis often endure prolonged delays.

Why care goes wrong

Better care for people experiencing sickle cell crises has been a struggle for many decades. The No One’s Listening report identified multiple roots of poor care, some of which implicate anti-Black racism.

Many hospital staff know little about SCD or how to treat it. Even in regions where SCD is common, hospital staff can be unsure of how to manage crises or may hold negative attitudes towards patients.

In most hospitals, crises are treated in emergency departments, which are now facing unprecedented pressure from increasing numbers of patients amid limited space and staffing.

The excruciating pain of a crisis means most patients need strong painkillers such as morphine to control the pain. Healthcare professionals must follow strict processes when prescribing and administering these medications, which can slow down care. Sometimes, hospital staff can unfairly assume addiction when sickle cell patients request strong painkillers.

Finally, in addition to SCD, Bayley lived with epilepsy and delusional disorder. Some SCD patients have additional medical conditions, and their symptoms can be difficult to identify or can be mistaken for another diagnosis. SCD patients with mental health disorders or intellectual disability face additional barriers in advocating for themselves.

How can sickle cell crisis care improve?

Specific treatments for SCD can reduce the frequency of crises. But compared with many other inherited medical conditions, SCD has very few available therapies. Slow progress in developing new treatments probably relates to disproportionately low funding and research into SCD.

For many SCD patients, existing treatments do not work or have severe side effects, and hopes for better options have repeatedly been dashed. After more than a decade without any new medicines, three new treatments for SCD have been licensed since 2020. However, in the last year, two were withdrawn and the other is not currently funded by the NHS.

Work to improve services is under way. NHS England is piloting dedicated sickle cell crisis centres in some locations, allowing patients to bypass emergency departments. Two-thirds of SCD patients in London now have a universal care plan – a digital crisis treatment plan which can be used in any hospital across the capital.

The No One’s Listening report also demanded better training for healthcare staff. This training must address both a lack of knowledge of the disease and negative perceptions of those with it. Attentive listening to people with SCD can make a significant difference.

As one patient writes: “My plea to doctors is to show empathy, release any negative preconceptions about how people manage pain, and prioritise resolving the pain so I can get home as soon as it is safe to do so.”

People living with SCD live rich, complex lives, just like anyone else, yet they endure levels of pain that most can hardly imagine. No changes can bring back the lives of Dave Onawelo and Wayne Bayley, and our thoughts are with their grieving families.

But improving treatment options, creating safer care systems and fostering more compassionate care will not only ease the suffering of people who live with SCD, it is likely to save lives.

Funmi Dasaolu receives funding from The National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Stephen Hibbs receives funding from the Wellcome Trust.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.