A shadow fleet of almost 1,000 ageing tankers – totalling 18.5 percent of global capacity – has been used since 2022 to dodge Western oil sanctions. These flag-hopping vessels with opaque ownership and frequent name changes ferry crude oil to Chinese "teapot" refineries from states including Russia, Venezuela and Iran.

On 1 October, 2025, French military personnel boarded the rust-streaked tanker Boracay just off the Bay of Biscay, after the captain, a Chinese national commanding a largely Chinese crew, ignored repeated orders to stop.

He was detained, and French prosecutors opened an investigation for refusal to obey a "lawful signal” and failing to prove the ship’s nationality – rendering it effectively stateless under international law, and boardable without flag-state consent.

On paper, the ship was registered in Benin, but this registration was marked “false” by the relevant shipping registries – the official records maintained by a flag state that document a vessel’s nationality and ownership, granting it the right to sail under that country's flag.

The Boracay also appears on several blacklists, including that of the European Union, as a ship that has been caught “transporting crude oil or petroleum products ... that originate in Russia or are exported from Russia while practising irregular and high-risk shipping practices”, as set out in resolutions of the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

Its detention in France was just another stopover on an erratic journey – one that exemplifies the global movements of Russia's shadow fleet.

EU hits Russia with sweeping new sanctions over Ukraine war

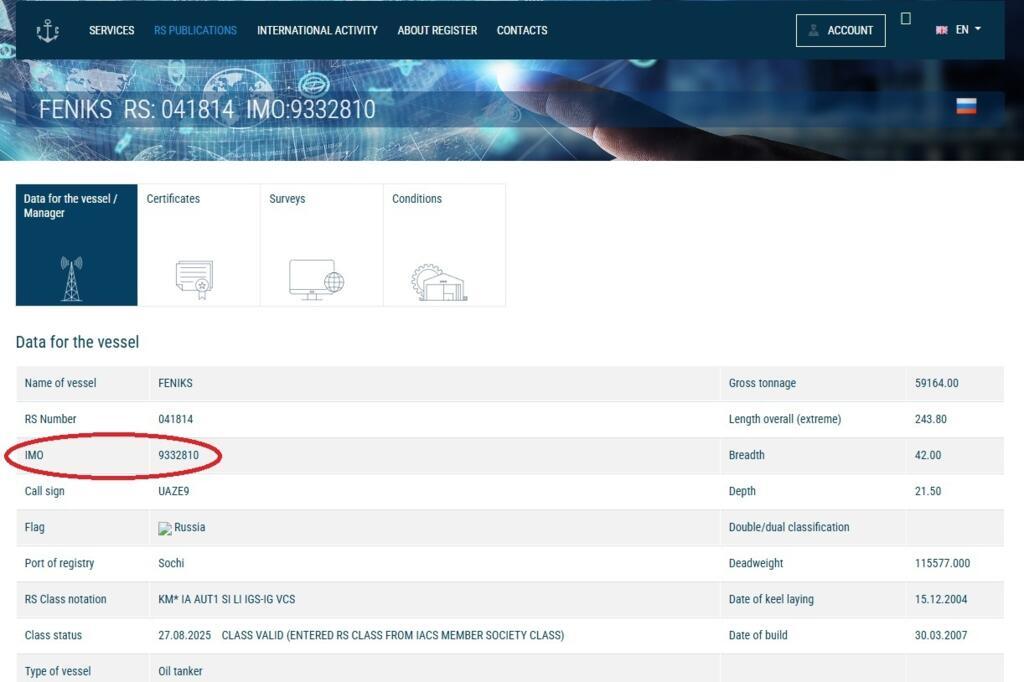

IMO 9332810

Launched in 2007 as Pacific Apollo, from a Japanese shipyard, the vessel is identifiable by its IMO number 9332810, the unique and unchangeable number assigned to every merchant ship for lifetime identification, regardless of name or flag changes.

It became Virgo Sun six years later, then sped through aliases from 2020: P. Fos, Odysseus, Varuna, Kiwala, Pushpa – and finally Boracay, from September 2025.

The vessel's flags shifted rapidly too: the Marshall Islands, St Kitts and Nevis, Mongolia, Gabon, Djibouti, Gambia, Malawi and Benin – several lacking valid registration, according to Equasis, the database of the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA).

'Name-hopping" is a hallmark of a so-called shadow fleet.

“There is no official definition of the shadow fleet,” according to Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council think tank.

"Different organisations use different definitions, but the characteristics that most of them include are flag-hopping, obscure ownership, uncertain P&I insurance, and the fact that they transport sanctioned cargo,” she told RFI.

The Boracay's managers have included India’s Gatik Ship Management, a leading carrier of Russian oil since Ukraine’s invasion, and Turkish firm Unic Tanker Ship Management.

UK armed forces helped US mission to seize Russian tanker, MoD says

Drone attacks

In April 2025, when it arrived in Estonia after a long journey from India’s Sikka port, Estonian naval forces detained the IMO 9332810, then under the name Kiwala and registered in Djibouti – despite Djibouti cancelling its registry months earlier.

The ship was on the EU sanctions list, and heading for Russia.

Estonian inspectors found 40 “deficiencies" – issues that didn’t conform to shipping regulations – with 23 of them documentation-related.

However, they had to release the ship as there wasn’t enough evidence to hold it indefinitely.

It reached the Russian port of Ust-Luga in late April, then Primorsk near St Petersburg in September and changed name, this time becoming the Pushpa. According to Eurasia Daily and other shipping publications, this time it was filled with petrol.

As the Pushpa continued its journey, Danish authorities then linked it to suspicious drone flights over airports, forcing closures, although proof remains elusive.

On it went, through the English Channel and then southwards.

According to data from the Marine Traffic tracking website, the ship had been scheduled to arrive in Vadinar in north-western India on 20 October.

But it was followed by a French warship and local authorities boarded the ship – by now named the Boracay – off the coast near Saint-Nazare, and detained it.

Shadow fleet targeted as EU advances frozen assets plan for Ukraine

With the detention of the Boracay, French President Emmanuel Macron was fulfilling a promise that France and its EU partners would pursue a “policy of obstruction” against such shadow-fleet vessels.

However, it is not always easy to determine when maritime rules permit the physical challenge of these clandestine vessels.

“You can board and you can possibly detain if you have strong suspicions and allegations, but then if you can’t prove beyond reasonable doubt that that ship has been involved in some kind of crime, then you have to release it,” explains Braw.

She added: "Every vessel in the world has the right to sail on the world’s oceans... these shadow vessels don’t sail in the territorial waters of Western countries, they sail in the exclusive economic zone, where coastal states have fewer rights.”

The capture of the Boracay and the more recent detention of ships leaving Venezuela by United States forces are rare examples of national authorities taking action against the shadow fleet.

According to Braw, critics who have called Europe “spineless” in this regard often miss the point that governments follow the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS,) making "systematic action against the shadow fleet... very difficult without stretching or violating maritime rules".

Opaque ownership

Since its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and subsequent sanctions, Russia has stepped up use of this fleet of ageing tankers with opaque ownership and shifting identities to circumnavigate Western restrictions on its oil exports.

When the G7 imposed a $60 per barrel price cap on Russian oil in December 2022, this shadow fleet trafficking of Russian oil exploded.

Today, S&P Global counts 978 tankers totalling 127 million deadweight tonnes – 18.5 percent of global capacity – with 54 of these vessels (9.5 million payload tonnes) being used for Venezuelan crude swaps.

"There is no official definition, no official list and no precise number,” says Braw. The EU’s 18 December, 2025 sanctions hit 605 vessels, nine enablers (including owners and shipping companies) as well as firms in the UAE, Vietnam and Russia; yet port bans are not universally applied.

EU on track to end Russian gas imports by end of 2027

Global reach

The recent US detention of two Venezuelan tankers, thought to be shipping sanctioned oil, exposed the fleet's global reach.

Roughly 80 percent of Venezuela's 1 million barrels per day flowed to China, says Eric Olander, co-founder of the China-Global South Project, adding that: "The vast majority of the oil that Venezuela was producing was going to China.” The majority arrived at its destination via the shadow fleet.

For Beijing, this is just a small slice of its total oil imports – some 4 percent.

Venezuelan heavy, sour crude oil is hard to refine. But smaller, independent refineries, mainly located in China’s eastern Shandong province – nicknamed “teapots” – specialise in processing this oil from Venezuela and Iran, and are dependent on it.

"The teapot refineries will be the most impacted because they have tuned their systems to these particular grades of crude from Iran and from Venezuela,” according to Olander.

Unlike Chinese oil giants Sinopec or PetroChina, “teapots" lack diversification. With Iranian oil comprising 14 percent of imports, combined Venezuelan-Iranian pressure could hit 20 percent of China's barrel basket.

Meanwhile, French authorities released the Boracay after a detention of just a few days. At the time of writing, it was located in Malaysia.

The ship now also appears on the Russian maritime register, under the name Feniks and registered to the Russian port of Sochi – a move that could suggest acknowledgement by Russia of its involvement with this shadow fleet.