"Dark comets," which are near-Earth asteroids that behave like comets and could contain water ice, have mostly come from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and could make up as much as 60% of all near-Earth objects, a new study suggests.

Dark comets were first revealed in 2023, when a team led by Darryl Seligman of Cornell University identified six of them based on their anomalous motions.

Asteroids follow orbits dictated by the sun's gravity. However, the six objects identified by Seligman's team display an orbital acceleration that cannot be explained by gravity alone. Such motion is not unfamiliar — we see it all the time with comets, which receive an extra push when they heat up and their ices sublimate, creating outgassing that can speed them up and alter their orbital trajectory, while the material that is outgassed forms a comet's tail and coma (the fuzzy cloud around the head of a comet).

However, the six objects found by Seligman's team don't have a coma or tail. In fact, they have no visible outgassing at all, but their non-gravitational acceleration tells us that there must be some, presumably caused by the sublimation of subsurface ice. Hence the nickname "dark comets."

Related: Comets: Everything you need to know about the 'dirty snowballs' of space

Now, new research led by Aster Taylor of the University of Michigan, whose team includes Seligman, has found where these dark comets come from. By applying dynamical modeling techniques in computer simulations, Taylor's group was able to replicate the orbits of the dark comets, showing that they can end up in near-Earth orbits if they start out in the inner region of the asteroid belt. There is one possible exception: One of the discovered objects, the dark comet 2003 RM, could have once been what's called a Jupiter-family comet, which typically have orbits that take them out as far as Jupiter before coming back in toward Earth. Another possibility is that it came from the outer edge of the asteroid belt instead.

The findings solidify an earlier theory dating back to the 1980s that predicts there's a lot of water ice buried beneath the surface of objects in the asteroid belt. NASA's Dawn mission found ice on the dwarf planet Ceres and strong hints of ice on the asteroid Vesta, both of which are the main asteroid belt. However, both Ceres and Vesta are much larger than most asteroids, and are considered to be the remains of protoplanets that were never accreted into fully fledged planets back at the dawn of the solar system.

It was not clear if water ice is commonly present on much smaller asteroids, but the dark-comet studies suggest that it is.

The new findings are supported by previous observations of other objects that blur the line between comets and asteroids. So-called "active asteroids" are bodies in the asteroid belt that behave like comets, with visible outgassing and even small tails. However, their existence is mysterious — are they asteroids that have accrued some ice, or are they comets from the edge of the solar system that have become trapped in the asteroid belt on their journey around the sun?

The connection between active asteroids and dark comets is still being debated, but Taylor suggests that dark comets, and possibly active asteroids, could be a source of Earth's water.

"We don't know if these dark comets delivered water to Earth," Taylor said in a statement. "We can't say that, but we can say that there is still a debate over how exactly the Earth's water got here. The work we've done has shown that this is another pathway to get ice from somewhere in the rest of the solar system to the Earth's environment."

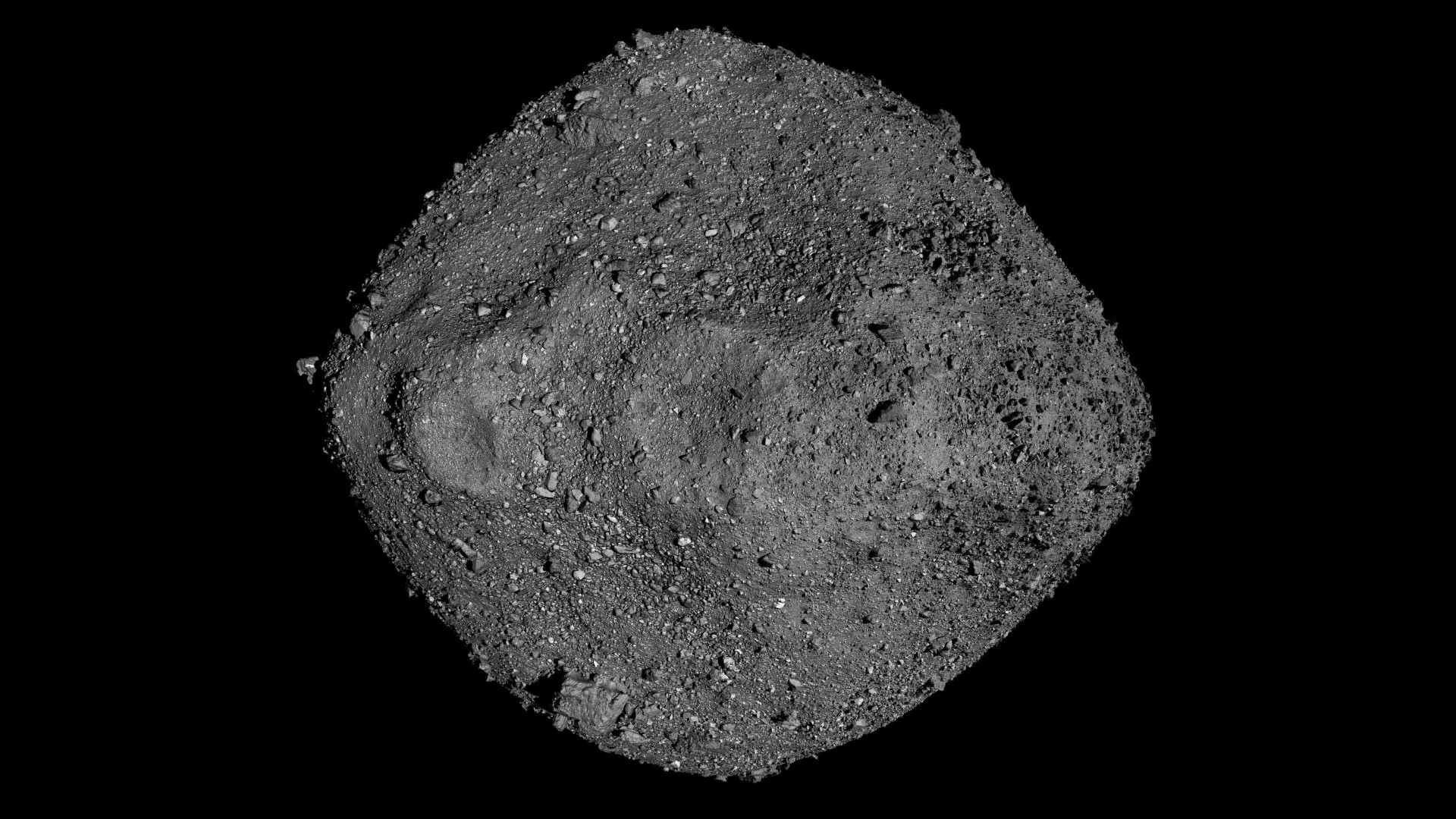

Taylor's team's calculations and modeling suggests that up to 60% of the near-Earth object population could be dark comets. Even the asteroid Bennu, recently visited by NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission, displayed some subtle outgassing activity when seen up close, implying that asteroids that outgas at levels too minor to be seen from Earth could be common.

The lifetime of objects that orbit near Earth is only about 10 million years before gravitational forces scatter them into the sun, toward Jupiter or into a planet. So dark comets must be being constantly replenished with fresh objects from the asteroid belt to maintain the current numbers near Earth.

"There may be more ice in the inner main [asteroid] belt than we thought," said Taylor. "There may be more objects like this out there. This could be a significant fraction of the nearest population."

With the exception of 2003 RM, dark comets are typically small — just a few dozen meters or so across — and are spinning quickly. The outgassing, which must be a fairly modest amount since we cannot see it directly, is also to blame for the fast rotations and small sizes of the dark comets. When patches of ice begin to sublimate, the resulting vapor bursts through the asteroid's surface and creates plumes of outgassing material from different locations on an asteroid. The momentum imparted by this outgassing can send the asteroid spinning fast enough to eventually break apart. The resulting fragments then also begin spinning as they outgas, and gradually they whittle themselves down to the size of the tiny dark comets that we see today.

"What we suggest is that the way you get these small, fast-rotating objects is, you take a few bigger objects and break them into pieces," said Taylor.

It's also possible that we've seen a dark comet before. In 2017 the first known interstellar object, 'Oumuamua, passed through the inner solar system. It experienced non-gravitational acceleration despite no comet-like outgassing having been detected. This led to somewhat wild claims that 'Oumuamua may actually be a spacecraft traveling under the power of a solar sail. However, the discovery of natural dark comets native to our solar system and which also exhibit non-gravitational acceleration while having no visible outgassing is too similar to 'Oumuamua to not draw comparisons. It therefore does not seem outlandish to suggest that 'Oumuamua was also some form of dark comet, rather than a spaceship.

Taylor's findings describing the origins of dark comets was published on July 6 in the journal Icarus.