In the video game Grounded, you play as a human shrunk down to the size of an ant who’s forced to survive the perils of a suburban backyard, including mites, beetles, and mosquitos. But when Obsidian Entertainment was developing the game, it found that one critter, in particular, posed a problem: its elephant-sized spiders were just too scary for what was otherwise a kid-friendly action-adventure romp.

The solution was an optional Arachnophobia Mode, which gameplay programmer Brian MacIntosh developed in partnership with the Xbox User Research Lab. The mode gives Grounded’s spiders a more friendly appearance, like two round blobs. But that wasn’t Obsidian’s first solution.

“Initially, I thought we could solve the problem by hiding a particular feature of the spider, like its legs,” MacIntosh tells Inverse. “What we learned is that it’s not one specific feature that causes the phobia reaction, but the player’s holistic identification of, ‘That’s a spider.’”

Using Arachnophobia Mode, players can manipulate a slider that gradually removes the critter’s legs, fangs, and even a select number of its eyes. Spiders attack with the same aggression and damage regardless of appearance. With a simple fix, Obsidian turned a potential barrier to entry into a meme embraced by Grounded fans who affectionally refer to the creatures as “danger dumplings.” The idea has caught on with other developers, too. The new Star Wars game, Jedi: Survivor, also offers an arachnophobia setting to make some of its aliens less spider-like.

More importantly, Arachnophobia Mode was also a significant step forward for accessibility in gaming. Video game accessibility is typically divided into three main categories: mobility, auditory, and visual. Customizable controls, subtitles, and audio descriptions can profoundly reduce potential barriers within games. But players with mental health conditions have often found themselves left out of those innovations. Now, that’s finally beginning to change.

Trigger Warning

The most basic form of mental health accessibility is content warnings. The 2017 visual novel Doki Doki Literature Club alerts players of potentially upsetting topics at the beginning of the game and throughout the experience. Content warnings allow some players to prepare for disturbing moments, but they’re often intentionally broad to avoid spoilers.

For Senior Xbox Game Studios Lead Tara Voelker, who lives with PTSD, these types of content warnings aren’t just a nice perk, they’re a necessity.“For me, it’s not that a game having a specific type of content is something that I want to avoid completely — I just need to intentionally opt into that experience,” Voelker says. “When certain sensitive topics surprise me when I’m not prepared for them, it can cause a flashback experience. My brain becomes flooded with traumatic experiences, and I physically feel whatever it was happening again.” The effects of these flashbacks can last for days.

Voelker notes that most content warnings are too vague to be helpful. She specifically calls out The Medium, a psychological horror game released in 2021 that contains discussion of child sexual assault, pedophilia, rape, the Holocaust, and suicide, but fails to spell that out ahead of time.

“The Medium does offer a trigger warning at the beginning, but it is so incredibly vague I do not know who it could have helped,” Voelker says. “Some sensitive topics I am totally fine with and will never trigger me, but others will. So, by saying something generic like ‘sensitive topics,’ I have no idea if it’s something I can handle that day.”

Rate Smarter

Content warnings are a necessary tool, but those warnings need to be as specific as possible to truly benefit the players who need them. Kelli Dunlap is a clinical psychologist who teaches at American University’s Game Center and community director for Take This, an organization that works to destigmatize mental health issues in the games industry. She says that ESRB ratings don’t go far enough to inform players of potentially triggering content.

“People need information to make an informed choice, and the information provided by ESRB content descriptors just doesn’t cut it,” Dunlap tells Inverse.

She points to two video games rated T for Teen that fail to disclose the complicated topics they explore. The Entertainment Software Rating Board notes that What Remains of Edith Finch features violence, blood, drug reference, and language, but doesn’t warn players that it also depicts the death of an infant, child death, suicide, cancer, and intergenerational trauma. Similarly, Sea of Solitude’s rating calls out “fantasy violence and language,” but fails to mention topics like depression, extreme bullying, domestic abuse, and substance abuse.

Dunlap adds that developers need to be mindful of including outdated and harmful stereotypes about mental health in their games.

“It could be characters talking about or experiencing mental health challenges. It could be mechanics like sanity meters, or environments and ephemera like a psychiatric hospital full of straight jackets and electroshock therapy machines,” she says. “Are these representations necessary? Or are they just flavor, something added without thought?”

Changing The Game

Content warnings are one thing, but removing the accessibility barrier itself gives players the chance to actually experience these games, rather than just avoid them. Some recent titles, like Grounded with its “danger dumpling” spiders, have gone the route of modifying or removing the triggering content entirely.

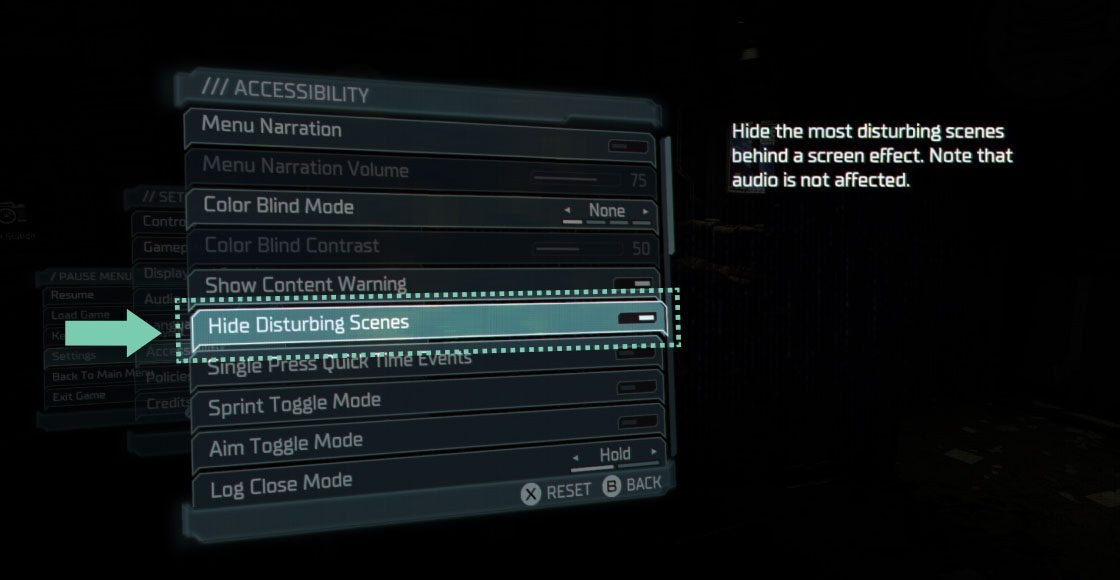

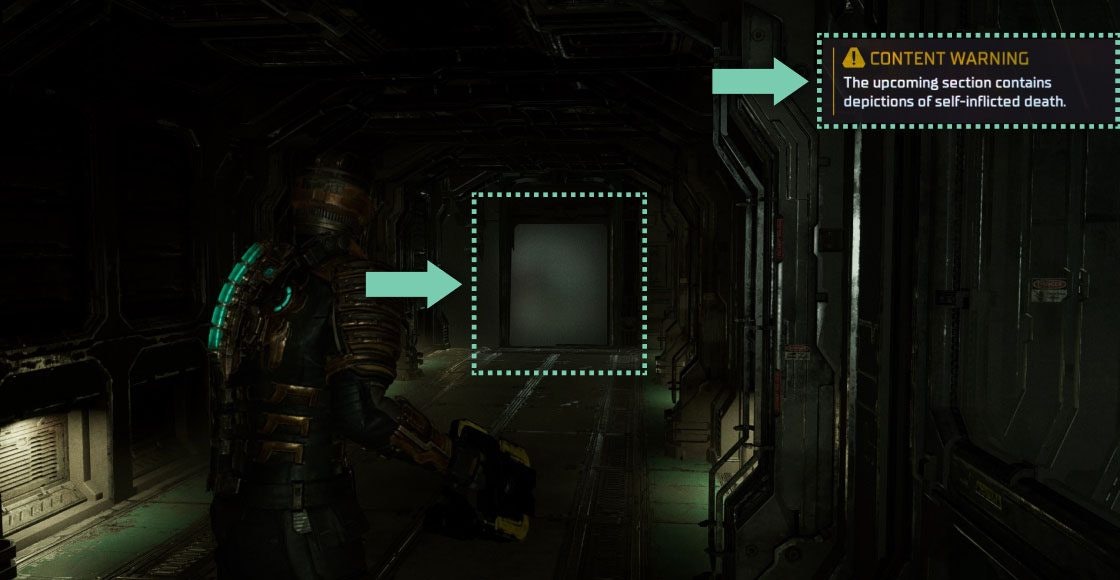

The 2023 remake of the survival horror game Dead Space gives players the option to blur instances of self-harm and gratuitous violence. Text logs that reference these themes can also be censored at a player’s discretion. The content may be less explicit for certain gory moments, but the core experience remains the same for every player. Dead Space’s extensive options fit seamlessly within the game’s core design, only affecting brief cutscenes or pieces of lore. Players still experience an immense feeling of isolation and dread as Isaac Clarke fights to survive.

While it may seem counterintuitive, Dead Space demonstrates how the horror genre can lead to innovation in mental health accessibility.

“You can absolutely make horror games accessible to people with mental health challenges,” Dunlap says. “If you’re including mental health-related content, do so with intention and an eye toward avoiding stereotypes.”

Grounded’s Arachnophobia Mode made proved beneficial for the development team, too. MacIntosh says the research behind the setting can be applied to future titles, further refining the option to appropriately fit new gameplay experiences.

“We’ve considered supporting other creature phobia modes, but it becomes a much more difficult task when every creature in the game is an insect,” Gameplay Programmer Brian MacIntosh says. “If we apply the same ‘danger dumpling’ approach to all of them, every creature silhouette becomes a blob of blobs, making it much more difficult to tell them apart. But we have this knowledge to keep in mind for the studio’s future games. If any might feature the occasional insect enemy, as RPGs often do, we can use what we’ve learned to make safe variants for them.”

Dead Space and Grounded both attest to the boundless potential for developers to create solutions that allow more people to enjoy their games. With mental health accessibility, candid communication with the player community will be key to furthering innovation in the months and years ahead.

“Let players know what they’re in for, or at least give them the option to be alerted,” says Dunlap. “Give players as many tools as possible to make an informed decision and empower them to navigate difficult content based on their own needs.”