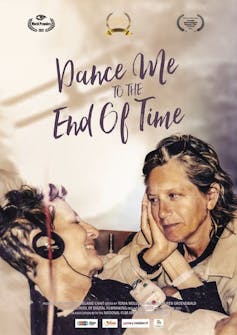

In her 2021 documentary Dance Me to the End of Time, South African film-maker and educator Melanie Chait has produced a truly great film. Not only for the breadth of themes it broaches – from cancer to green activism, from lesbian love to arts therapy – but also for the intensity with which she deals with these themes.

One of the hallmarks of a great film is its ability to transport audiences; to hold their undivided attention and evoke deep emotions in them. The documentary does this, as it pieces together four years of home movie footage filmed by Chait.

Read more: How a film is fighting the erasure of South African activist Dulcie September

This very personal, award-winning film chronicles the final years and death of Chait’s life partner, London theatre director Nancy Diuguid. Diuguid died from breast cancer. The film is, of course, more than just about the death of Diuguid. It is also about the triumph of lesbian love in the face of death as well as the ecological and feminist politics of Chait and Diuguid.

In the process it elevates itself above death and disease to become a veritable celebration of life and love. Powerfully original, it is also likely to change the way people think about the food they eat and how it is produced. This is particularly important given the ever increasing prevalence of cancers.

The art of death

Dance Me to the End of Time has been enjoying a successful festival run after premiering at the Encounters documentary festival in South Africa and has won several international awards.

The documentary fits into a genre of film-making which focuses on disease, dying and death. This genre was popularised in the early 1990s by films which documented the death of people living with AIDS. These are films such as Silverlake Life by US director Tom Joslin and Modesty and Shame by French writer and photographer Hervé Guibert. I argue in an article on this genre that there is something more to such films than just the representation of diseased bodies and slow deaths.

Dance Me to the End of Time shows how two women face the presence and reality of death. Diuguid thinks through how, although she was losing control of her body, she still wanted to be “present in the process of dying”. Chait contends with the idea of losing her loved one. She expresses her helplessness in offering the comfort that her dying lover required:

It felt like I was playing God: deciding what to do, when. Nancy was so unlike the Nancy I had known. I only wished I could do better with the process of knowing how to comfort and help ease her anguish.

Despite the difficult conversations they have about death and the meaning of loneliness, it’s fascinating how the film eloquently demonstrates that even in the face of death, the couple was able to experience happiness. In many instances, Diuguid is filmed swimming in the ocean or dancing with their adopted son, Desmond. This film is a beautiful ode to lesbian love, an elegy of two women loving one another through sickness and health.

Ecological and feminist politics

Chait also weaves into this personal story the important feminist and ecological work that the couple did to expose the health dangers of pesticides. When diagnosed with cancer, Diuguid decided to adopt a holistic, integrated medical approach combining traditional medicine and natural methods.

The story of US scientist and ecologist Rachel Carson is woven into that of Chait and Diuguid. From as far back as the early 1960s, Carson had exposed the health hazards of pesticides, especially DDT, used to spray farm crops. Diuguid grew up on a farm in Kentucky and experienced how small wildlife would be killed days after the spraying of their farm.

Diuguid and Carson both died of cancer. By drawing parallels between their lives, the film highlights the politics of what and who is responsible for causing cancer. In its focus on the gruesomeness of the effects on cancer, Dance Me to the End of Time is itself political in dealing with ecological questions and the impact of pesticides.

The film also shows how, when Diuguid was diagnosed, she was able to use the creative arts and her lesbian identity as tools to campaign for justice and to heal others. Through an initiative called VOICES, she used expressive arts to help women and children deal with trauma in the townships of Johannesburg. In addition to the historical trauma of apartheid, townships in South Africa have had to do contend with high levels of intimate forms of violence.

Vulnerability and dignity

Even in chronicling Diuguid’s dying, the film does not rob her of her dignity and humanity.

In fact, the film celebrates her life and her important work in expressive arts therapy.

In its personal and deeply emotional texture, Dance Me to The End of Time offers a sincere depiction of how to face death and more importantly how to live life to its fullest.

The film will be screened on 5 March as part of Cape Town Pride.

Gibson Ncube does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.