The Accommodation begins with the bombings. The 1950s terror spree that racist Dallasites unleashed on Black residents who’d dared buy homes in a then-white neighborhood. The dozen or so packages of dynamite hurled at South Dallas houses that rocked the city, yet led to no criminal conviction. The shameful episode that local elites have fought to see forgotten but that, the book’s author writes, sprung “right up out of the spiritual heart of the white community, the heart darkened by nineteenth-century specters.”

A 34-year-old work set for republication this September, The Accommodation is an unusual book with an unusual backstory. Jim Schutze, a long-time acerbic city columnist and white man, wrote the text in the mid-1980s after many evenings buried in Dallas Public Library archives. The end-product may fairly be called a journalistic account, blending straight reportage and opinionated analysis, of race and civil rights in mid-20th century Dallas. But the 260-page book is also amateur history and historiographical critique, newsy play-by-play and grand political theory. It is a fierce indictment, occasionally indiscriminate and overwrought, that still hits its target. It is, perhaps above all, a pleasure to read.

The Accommodation almost never saw the light of day. In 1986, the book’s Dallas-based publisher unexpectedly scrapped it due to either poor pre-sales or political pressure, depending on who you ask. A year later, a New Jersey press gave the book a small release but decided against a second run. Schutze then handed over the rights to Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, who pledged to find a publisher, but after the two men had a falling out, Schutze says, Price simply sat on the book for decades. Thus, an obscure book’s legend grew.

Like literary contraband, young Dallasites over the last decade passed around a Dropbox link leading to a photocopied version of the book. No one seems sure who made the copy. On Amazon, The Accommodation listed for hundreds of dollars and D Magazine profiled the phenomenon in a piece titled “The Most Dangerous Book in Dallas.” As the now-75-year-old Schutze interprets it, millennial-age residents were encountering a Dallas still viciously riven by a north-south divide and allergic to talking about why. His book spoke to a burning question: “Why is the city like this?” Now, with Price’s blessing, the local publisher Deep Vellum will let everyone digest Schutze’s answers.

The book’s thesis is this: Dallas, despite its boosters’ claims, is a place crafted stem to stern by white supremacist violence and expropriation. Yet, through an anti-democratic alliance between the city’s business class and conservative Black clergy members, Dallas managed to avoid the riotous convulsions of the civil rights era seen elsewhere in America. The city maintained a relative peace with precious little justice, the titular “accommodation,” which Schutze believes hampered the development of independent Black leadership and the advancement of white attitudes.

“Dallas commands a part of Texas that is much more Southern, with stronger roots in slave culture, than many outsiders realize,” Schutze writes. To make the case, he recounts the 19th-century influx of enslavers to North Texas, where he argues slavery then was likely even crueller than in the Deep South. He reviews post-Civil War federal reports recounting floggings and murders that permeated Dallas, and describes the city in the 1920s as a hotbed of KKK activity. As the Black middle class fitfully grew, he describes how the city used “legal hocus pocus” to vaporize property rights, clear neighborhoods, and push as many Black residents as possible into segregated housing projects. These very pressures, he details, led Black housebuyers to venture into South Dallas, where working-class whites responded with dynamite.

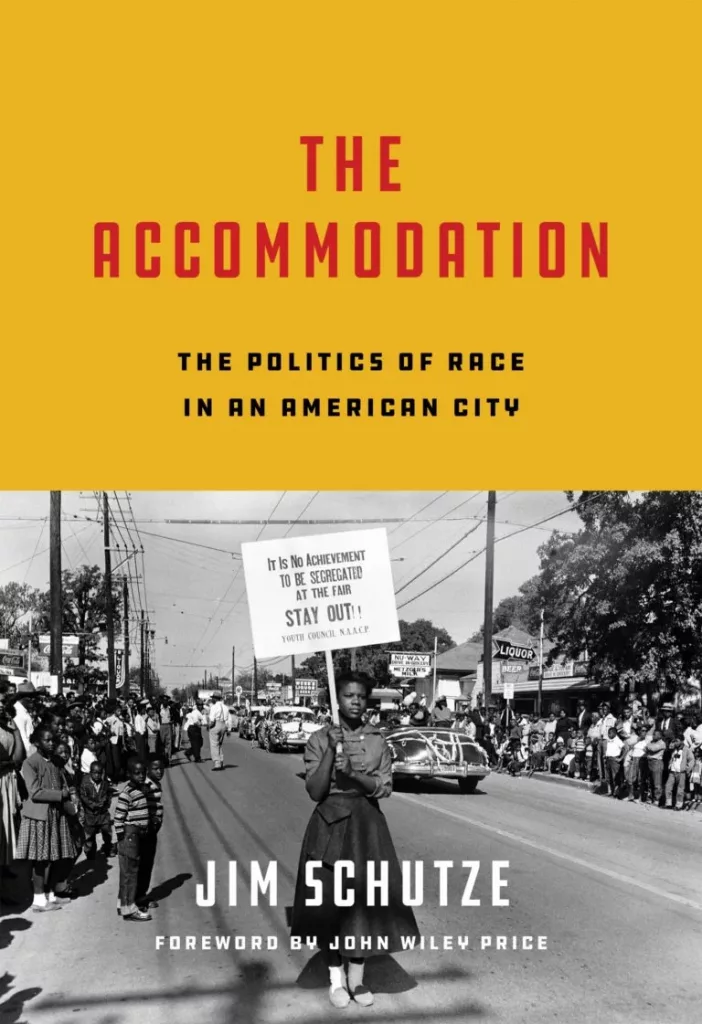

Black Dallasites fought back, defending their homes with guns as necessary, but—in Shutze’s telling—the public square stayed rather quiet. Bull Connor sicced his dogs in Birmingham and Watts burned in Los Angeles, but Dallas saw just a few picket lines outside downtown stores. The key player, he says, was the Citizens Council, a coterie of business elites that controlled the city council, elected entirely at-large, and ran Dallas like a “pre-democratic city-state.” With a fine-tuned sense of when to co-opt a leader or cut ties with one who veers too far-right, the council was adept at propaganda and substituting tokenistic reforms for justice. The group ultimately sowed the enduring myth of Dallas as a rational Southwestern city of convenient commerce. Members of the Citizens Council also composed the grand jury that, after finding the 1950s bombings plot involved respected white community leaders, asked to be disbanded. Still, the city did not burn, and blatant segregation persisted from the State Fair to graduation ceremonies.

For Schutze, a turning point came finally in the late ‘70s, when a movement of Black homeowners spearheaded a lawsuit that overturned the at-large city council system, leading to district elections that the Citizens Council couldn’t control. The book ends hopefully. But, in a new foreword, County Commissioner Price argues that little has actually changed in Dallas—even in today’s era of Black Lives Matter uprisings—and many locals still see the city as a uniquely white-washed place.

Jerry Hawkins, now the director of Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation—an anti-racist nonprofit—was one of those Dallas residents who discovered The Accommodation through a Dropbox link years ago. He tore through the PDFs. “These were things I had never heard of,” he says. “Nobody talked about this stuff.”

Hawkins says he’s shared the photocopied version with numerous acquaintances, and he references it at talks where he finds that even lifelong Dallasites don’t know the history of the bombings and similar events. He says The Accommodation spreads well thanks to its reputation as a banned book and because it’s written “like a telenovela.” With a friend, Hawkins formed a reading group to discuss each chapter. “This book has created a whole bunch of other things,” he says, noting that the actor William Jackson Harper, a Dallas native, wrote a 2018 play based on the story.

At the same time, Hawkins doesn’t actually buy a core piece of the book’s thesis. He thinks Schutze undersells the history of Black activism in Dallas, not because of ill will but because of ignorance. “The notion that Dallas didn’t really have a civil rights movement is kind of a myth that’s perpetrated in the way the author tells the tale,” he says. “I’m not saying he’s intentionally leaving things out. I’m saying he probably doesn’t even have the key to the door to get that information; I mean the Black Panther Party was in Dallas, and he’s not going to be in those meetings.”

Hawkins plans to help flesh out the story of Black Dallas himself. He’s editing a collection of essays called A People’s History of Dallas, set for release next year, and he’s researching another project, with a working title of “How to Build a Racist City.”

Schutze himself has called for further attempts to unravel Dallas’ past. In a recent article, he described his own book, with some exaggeration, as “the only attempt anybody has made so far to solve a glaring unavoidable riddle: Why is the city like this?” He then urged new and younger authors to soon produce “a better answer to the question.”