Plagiarism is a serious offense both in the academic world and in many workplaces. And high school is a great place for kids to make mistakes and learn about academic misconduct. Their missteps won’t result in any legal or monetary repercussions. Yet it can teach kids a lesson in what happens when you present someone else’s work as your own.

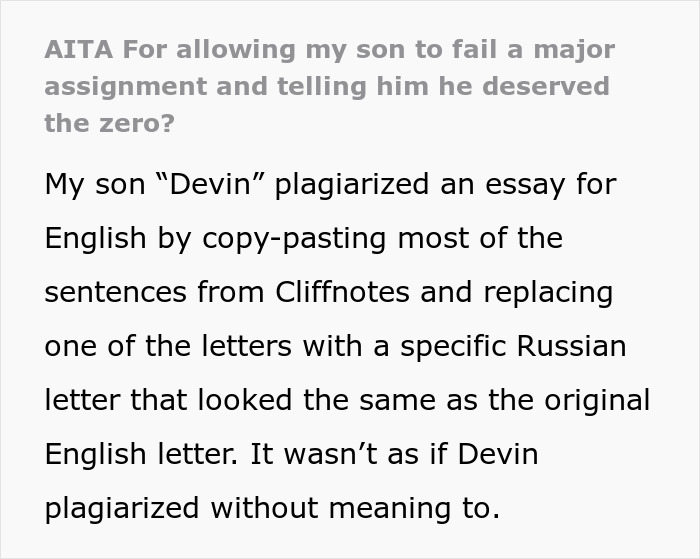

The parents in this story disagreed on what the right punishment for plagiarism should be. The dad, aka u/NotFixingSonsGrade, asked the Internet’s opinion on whether he was right not to challenge the zero his son got for plagiarizing an essay. The mother disagreed, claiming that this would impact the son’s academic future negatively. To better understand where the mother is coming from, the dad asked for more opinions. And the Internet delivered.

Plagiarism is stealing someone else’s work, it can destroy reputations and result in legal consequences

Image credits: drazenphoto /envato (not the actual photo)

This dad wanted his high-schooler son to learn this lesson the hard way but angered his mom in doing so

Image credits: LightFieldStudios / envato (not the actual photo)

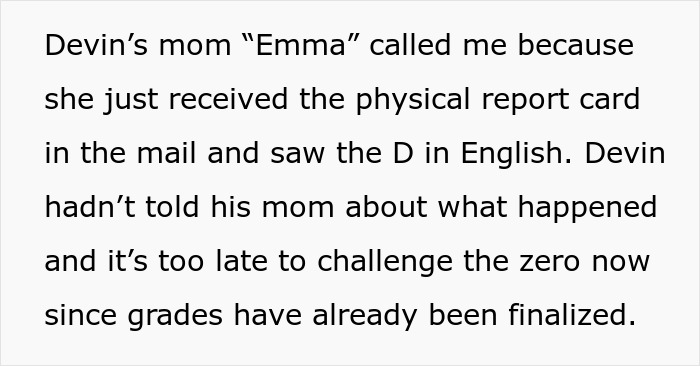

Image credits: NotFixingSonsGrade

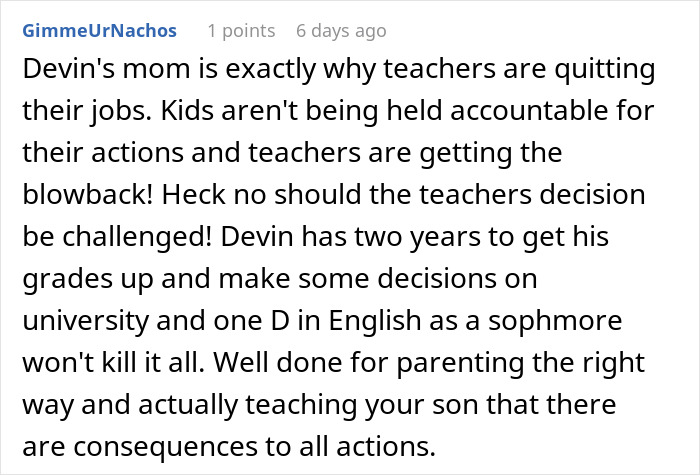

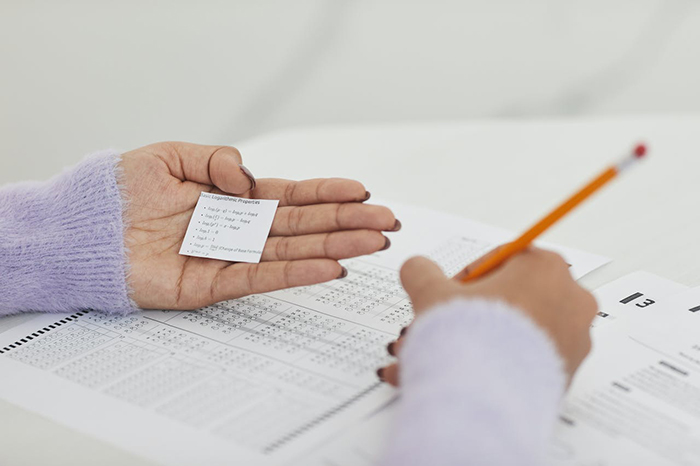

Telling your kid that cheating is okay is the same as telling them it’s okay to lie

Image credits: Mikhail Nilov / pexels (not the actual photo)

Cheating in high school is quite a common occurrence. Many of us probably have done it in one form or another. That’s one of the reasons why people (and adolescents especially) think it’s okay. Should parents let it go just because academic cheating is so commonplace?

Essentially, no, psychologist Carl E Pickhardt, Ph.D., writes for Psychology Today. He claims that “the core dynamic in cheating is too serious, too risky, and potentially too formative to ignore.” Pickhardt writes that cheating is the same as lying. And if a child believes that plagiarism and other forms of cheating are okay, they risk making a habit of lying.

The psychologist suggests emphasizing the consequences cheating will have on the child. It’s not so much a behavioral issue between the parent and the child. Parents should acknowledge why the kid decides to cheat and let them know the possible costs.

“Parents can declare that how much to cheat in school, and in life, is a matter of choice that people must weigh every step of the way,” Pickhardt writes. “They can explain: ‘How honest do I want to be?’ is a question everybody, young and old, asks all the time.”

Young students understand the moral dilemma of cheating, yet they still do it

Image credits: Andy Barbour / pexels (not the actual photo)

Researchers from the University of Virginia conducted a survey on teen moral formation in 2021. 83% of the respondents claimed they think honesty is very important, if not essential, to them. Qualities like ‘hard-working’, ‘reliable and dependent’ were more relevant than being ‘ambitious’ or ‘a leader.’

Yet, kids who want to be honest and know that cheating is wrong still do it. What are the roots of this discrepancy? Most research claims that personal and situational factors override this ideal. Either they’re afraid of failure or ease their guilt because ‘everyone else is doing it too.’

Research Professor of Sociology Joseph E. Davis, Ph.D., offers another reason. He says we should blame adults who send adolescents mixed messages in their most formative years. Adults tell teenagers that honesty and integrity are the standards they should meet. Yet, “they are regularly exposed to the idea that success involves a trade-off with honesty and that cheating behavior, though regrettable, is ‘real life.'”

Davis cites the 2012 Josephson Institute survey of 23,000 high school students. 57% of them said that “in the real world, successful people do what they have to do to win, even if others consider it cheating.” The professor observes that educational success becomes more important for the students than honesty.

Davis theorizes that the solution could be consistent norms, values and expectations. Achievement and the ‘real world’ shouldn’t be in opposition to honesty. “Rather than confronting students with trade-offs that incentivize ‘any means necessary,’ they would receive positive, consistent reinforcement to speak and act truthfully,” Davis writes.

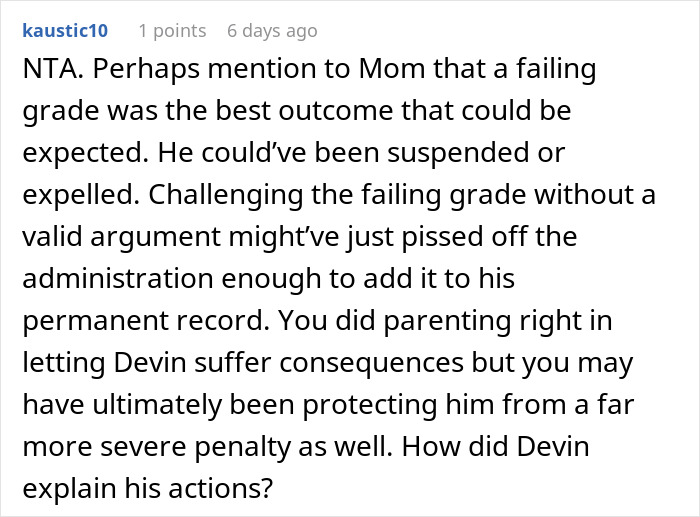

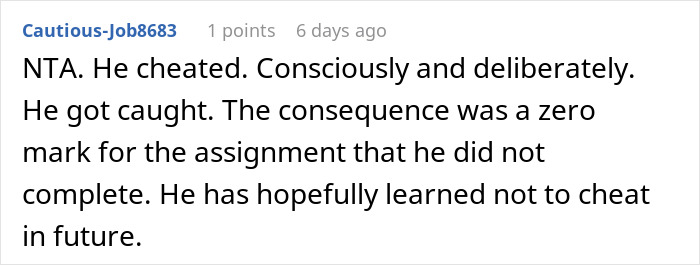

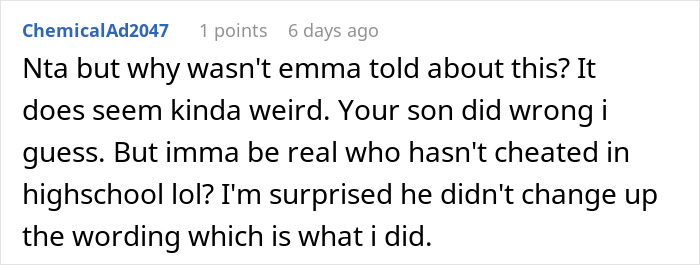

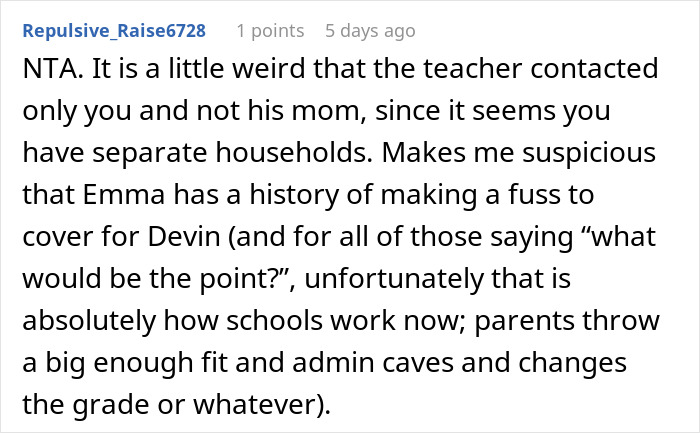

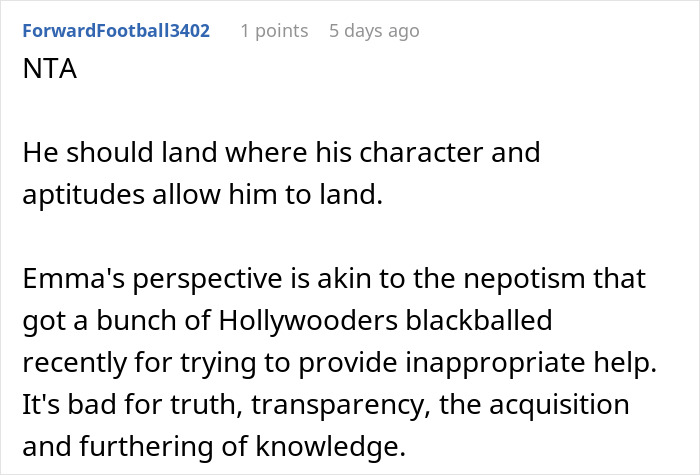

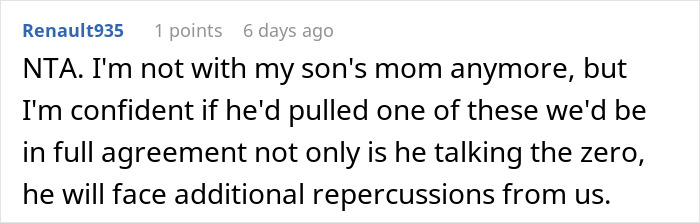

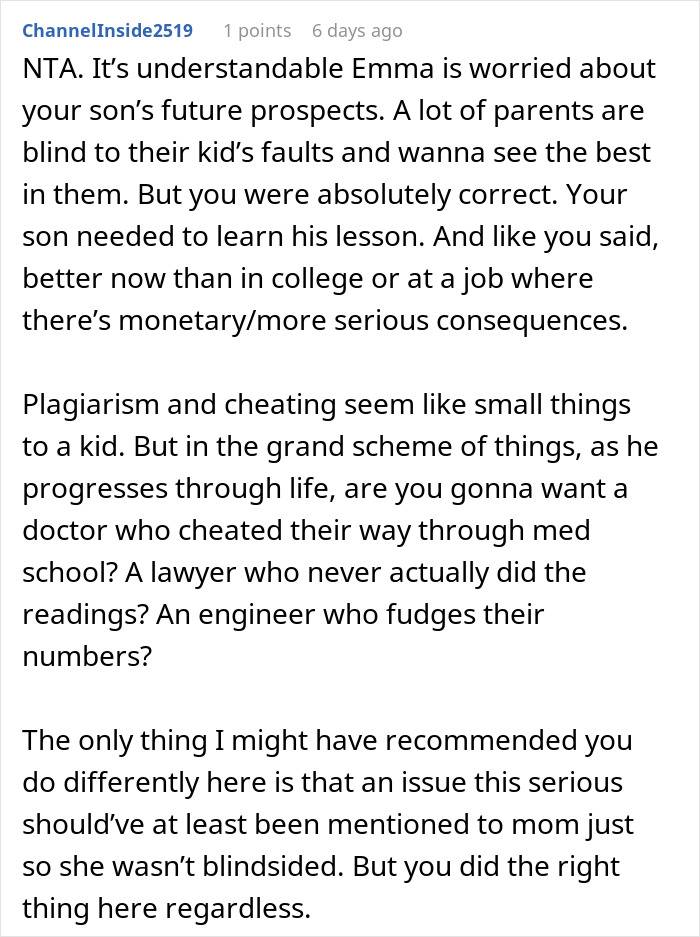

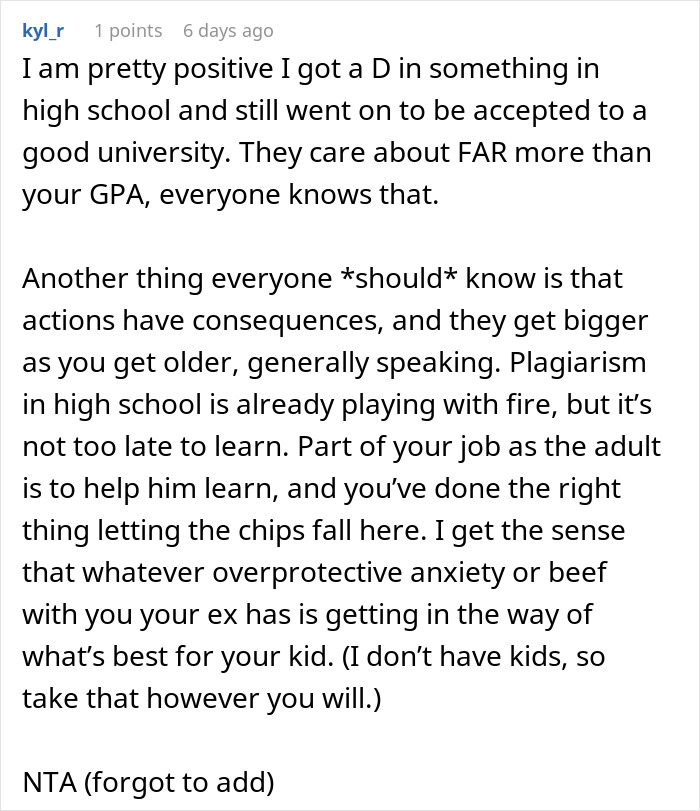

People in the comments agreed with the OP’s parenting technique