There’s an assumption among cyclists that riding a bike is as green as a gardener’s thumb. And it’s true, to an extent.

Environmentally speaking, bikes are significantly more sustainable than cars, trains or planes, both in the way they’re manufactured and the way we use them. But let’s not be fooled into thinking our pedal-powered companions come without a carbon footprint of their own.

From the moment the materials are extracted from the earth, to the final time we swing our leg over the saddle, our bikes are leaving an impact on the world. To find out how to minimise that, Cycling Weekly spoke to three experts, all involved in cycling, and all passionate about our planet’s future.

Here are the steps they said all of us can take to leave as little trace as possible, starting with the most impactful.

1. Ride more, not just for sport

If you’re reading this article, the chances are that you ride a bike, and for that you can give yourself a pat on the back. Still, in terms of sustainability, there’s a big difference between your Sunday café ride and your daily commute.

According to Erik Bronsvoort, sustainability expert and founder of Circular Cycling, our riding can only be considered green when it’s replacing a journey that would have been more damaging to the environment.

“A lot of bikes are never used for transport, they’re used for sport, and that has nothing to do with sustainability,” Bronsvoort said. “If we all start cycling more as transport, we reduce the use of other types of vehicles that have a way bigger impact on the environment.”

Last year in the UK, more than two thirds of trips between one and five miles were made by car. The most commonly cited purpose for these journeys was shopping, with commuting a close runner-up. It’s these short, five-minute engine spurts that are particularly bad for the planet, releasing a puff of polluting gases into the atmosphere, and wearing down the vehicle’s battery.

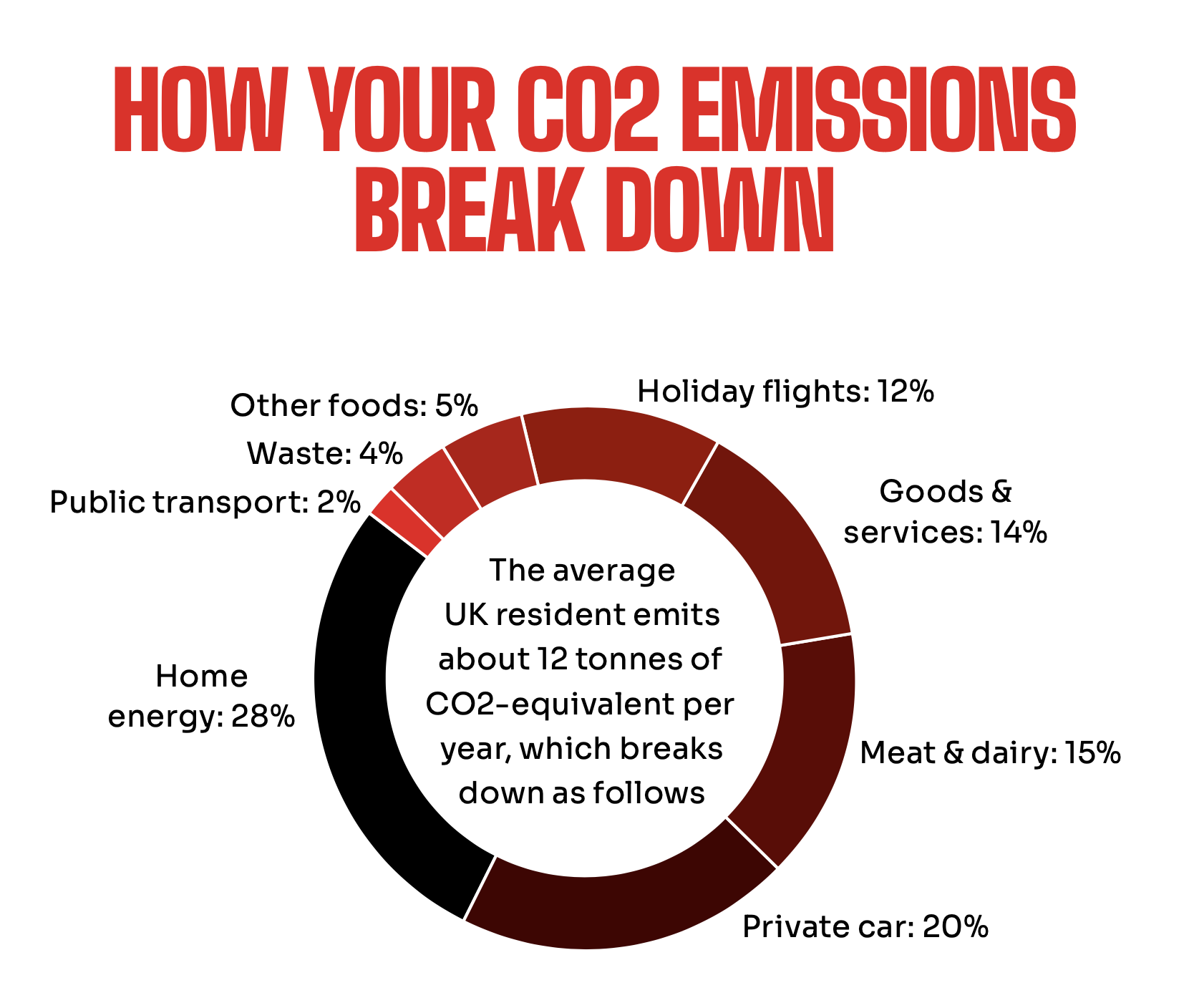

So next time you head out for that carton of milk, grab a rucksack and lock, hop on your bike, and pedal down to the supermarket. According to researchers at the University of Oxford, switching from a petrol car to a bike for just one trip per day can slash a person’s carbon emissions by half a tonne of CO2 equivalent each year – that’s almost 10% of their whole carbon footprint.

2. Keep your bike pristine

Look after your bike and your bike will look after the planet. That’s the motto of Dani Farrow, a fellow at Exeter University, who has worked with British Continental team Saint Piran on their net-zero ambitions. “One of the most important things you can do as a cyclist is keep your bike in a good condition, so that it lasts you for as long as it possibly can,” Farrow said.

“The fewer bikes I buy in my lifetime, the fewer need to be made, which means that I’ve reduced my environmental impact. That’s it in a nutshell.”

A key part of this is regularly washing away dirt and grime to keep your bike running smoothly. When doing this, use biodegradable products – brands such as Muc-Off and Fenwicks pride themselves on this – and clean often, particularly after riding in harsher weather. Eventually, individual parts, the chain, cassette or tyres, will need to be replaced, but try to extend their lifetime rather than swapping them every year. A well looked-after chain, for example, can last up to 4,000 miles.

Reducing the production of bikes and parts slashes emissions. According to manufacturer Trek, the average bike in their fleet generates 174kg of CO2 from start to finish of production. To offset this, the brand says that the owner of the bike will need to ride 430 miles that they would have otherwise driven. From then on, the bike is essentially carbon neutral, contributing to a more sustainable system. There’s no reason it can’t last a lifetime.

3. Buy responsibly

In the event you do need to buy a new bike, or parts, take a moment to think about the materials available to you. “In terms of longevity, ease of use, and ease of repair, the best is a steel frame bike,” said Alec Seaman, founding member of the Cycling Industries Europe sustainability expert group. Then comes aluminium and titanium, Seaman added – “they’re frames for life, they don’t rust”.

Carbon fibre, although lightweight, has sustainability limitations: it’s labour-intensive to make, and currently very difficult to recycle. Bonded together with epoxy glue, the carbon fibres have to be broken down in the process, making them shorter each time, and leaving them with fewer applications.

That said, it’s the lifespan you get out of your products that helps dictate their long-term sustainability. Bronsvoort follows a simple rule whenever he buys something new: “I always say, ‘If I like a product, I will buy it, but not within the next six months’,” he said. “If, after six months, I still think it’s the wheelset or the bike I’m in love with, then I make the purchase. The six-month rule provides a very good indicator that this product will be with me for a very long time afterwards.”

If you want to buy a cheap, second-hand bike, try sites such as The Bike Project, a charity that refurbishes and sells bikes, supporting refugees with the proceeds. For premium bikes, look at MyNextBike and Cycle Exchange, both of which sell pre-loved, top-of-the-range road bikes at slashed prices. Halfords also sell what they call “pre-pedalled” bikes at a cut cost.

4. Make your own snacks

Most of today’s high-end performance snacks, gels and energy bars, come in single-use wrappers, and can cost a fortune. Why not make your own mid-ride snacks? If you’re lacking inspiration, here’s a faithful flapjack recipe – the ingredients are all vegan, as studies have shown avoiding meat and dairy to be the single biggest way an individual can reduce their carbon footprint.

Don’t forget about the humble banana, either. It even comes in its own eco-friendly packaging.

Ingredients:

350g porridge oats

80g flour

Seeds, nuts, sultanas

200g vegan butter (Stork or Flora will do the trick)

175g golden syrup

200g soft brown sugar

Method:

Mix the porridge oats with the flour and your favourite seeds, nuts and sultanas. Next, melt the vegan butter and add to the mixing bowl, together with the golden syrup and the brown sugar. Grease a tray, pour in the flapjack mixture, and bake in the oven for half an hour at 160°C. Once they’ve cooled, you’re ready to pop them in resealable bags, and take them along on your next ride.

5. Recycle, if you must

“Recycling should be a last resort,” said Exeter University fellow Farrow. “We need to be thinking about other strategies before recycling. We’ve gone far beyond the ‘reduce-reuse-recycle’ to add in other strategies; we’ve also got repair, remanufacture and repurpose.”

At its core, recycling involves putting materials back into production, relying on machinery and energy to turn them into new products. When parts are scuppered, though, recycling is better than landfill.

Look at the Velorim website to find your nearest place for recycling inner tubes, tyres and lithium-ion e-bike batteries: the answer is often your local bike shop.

Brands, too, have begun recycling in-house, with Schwalbe recycling its one millionth inner tube this July. Still, Seaman stressed that fixing beats recycling: “There should be a degree of pride in pulling out an inner tube with 20 patches on it.”

All that’s metal – frames, chains and cassettes – can be taken to recycling centres or scrap metal dealers. Aluminium and steel are two of the world’s most recyclable materials.

6. Fly, but at a cost

A return flight from London Stansted to Palma de Mallorca bears the burden of half a tonne of CO2 equivalent per passenger. That’s the same as driving 1,250 miles in a standard petrol car, the distance from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Is there any way we can justify that warm weather cycling getaway? Well, maybe.

According to Seaman, we can look to offset those emissions in our own riding at home. “If you know that, for that trip to Mallorca and back, you have to commute to work 100 times, consider the benefit: it’ll get you as fit as a butcher’s dog when you go, and it’ll help you develop a real awareness of your carbon footprint,” he said.

The best option, though, is to seek alternative transport for your holiday – travelling by train produces 10 times less carbon than driving – or keep it local. Bronsvoort, a keen gravel racer, has been focusing his riding around the Netherlands where he lives. “I’ve been exploring my own country like never before, and I’ve really fallen in love with it again,” he said.

7. Use your voice

You don’t have to be Greta Thunberg to speak up about climate change. Often, big changes come from small actions, and a conversation with one person can snowball into something meaningful.

“Next time you’re in a bike shop, talk to the person in the shop about sustainability,” said Bronsvoort. “Write an email to the customer service of your favourite bike brand and tell them that you think this is important. It all helps. We need to get bike brands to be aware that consumers think this is an important topic. We need more people to raise their voices and say, ‘Guys, we want these sorts of products’.”

That way, we can all have our say in the long-term future of our industry.

This article was originally published in Cycling Weekly magazine. Subscribe now and never miss an issue.