It may have seemed inconceivable to scientists merely decades ago, but this dream is inching closer to reality thanks to recent leaps in reproductive technology: One day, couples assigned the same sex at birth may be able to have children that are genetically related to both parents.

Recently, scientists have made some breakthroughs, though only in lab mice. Over the past decade, some teams have harnessed genetic engineering to welcome a handful of rodents born from both male and female pairs into the world.

If these cutting-edge technologies are ethically and safely developed for humans, different types of families might be possible in the distant future.

“These researchers have been remarkably creative,” David Albertini, an embryologist at the Bedford Research Foundation, tells Inverse. “They kept Mother Nature in mind in their engineering approaches when building gametes — that is, sperm or eggs — out of stem cells.”

In vitro innovation

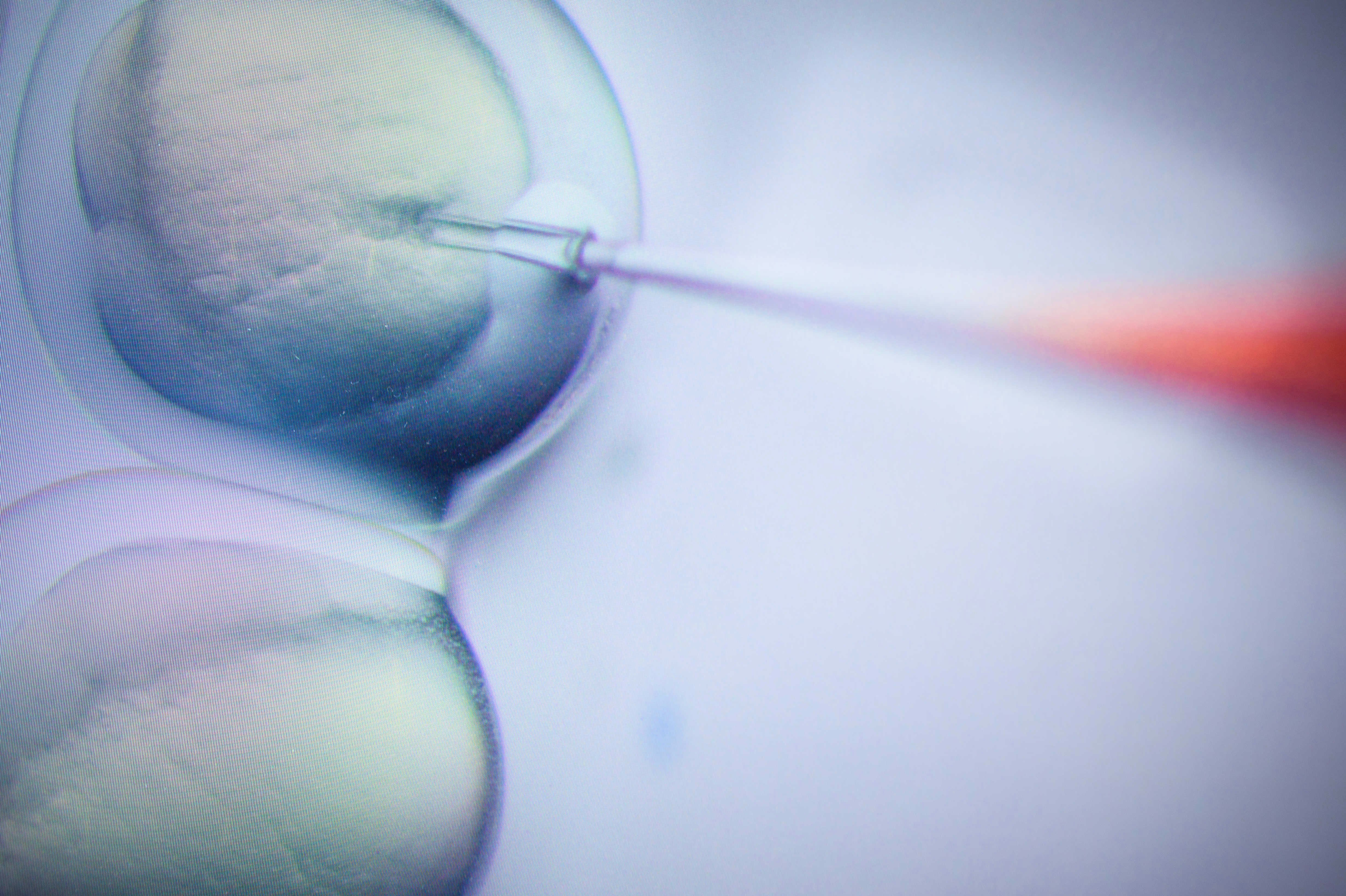

In a March study published in the journal Nature, a team of researchers in Japan reached a major breakthrough: The scientists created mice with two biological fathers for the first time. To achieve this, Katsuhiko Hayashi from Kyushu University and his co-authors used an innovative technique called in vitro gametogenesis, or IVG.

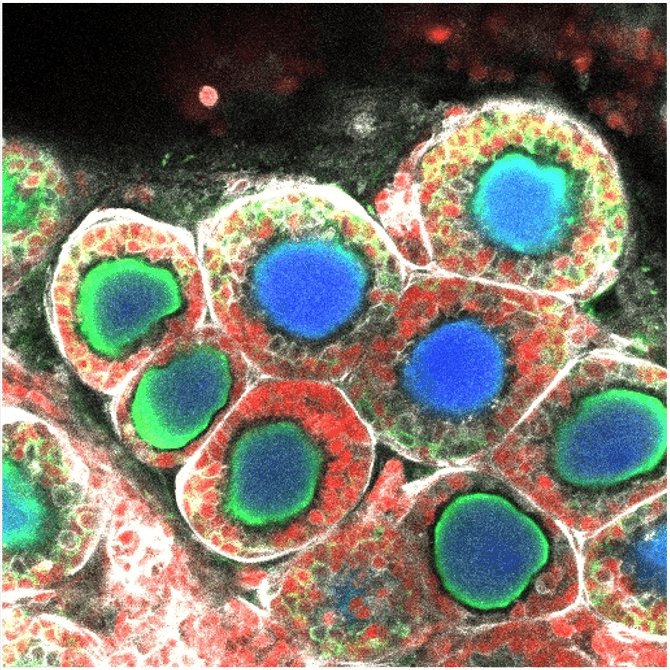

IVG works like this: Scientists can genetically reprogram cells from any tissue, such as skin or blood, into induced pluripotent stem cells or iPSCs, which are stem cells that can be turned into any other type of cell. From there, chemicals nudge these stem cells to become egg or sperm cells.

In the recent study, the team took tail skin cells from male mice and converted them to iPSCs. Then, they altered the genetic sex of these cells by coaxing them to ditch their Y chromosome and develop a second X chromosome, essentially forming eggs. Finally, these eggs were fertilized by another male mouse and transferred into the uterus of surrogate female mice to develop.

Hayashi and his colleagues transplanted 630 embryos formed from such egg cells into surrogate mice. But they only yielded seven healthy, living mice pups — a success rate of just over one percent.

A new frontier for queer couples

The milestone builds on Hayashi’s past breakthroughs. In 2011, his team created the first functional mouse sperm from stem cells. Then in 2016, Hayashi and another team from Tokyo University of Agriculture became the first to convert skin cells from mice into fertile eggs.

“This is a decade in the making,” Albertini, who wasn’t involved in the new research, says. “Hayashi and his team have been pretty much singular in their success with manipulating stem cells to make eggs and sperm.”

In theory, IVG foretells a future where scientists can take a small sliver of skin or blood from a human to create eggs and sperm, meaning a same-sex couple may be able to have a baby that shares both parents’ genes.

“This is a decade in the making.”

But this isn’t the only method that could transform fertility.

CRISPR-Cas9 technology is a gene editing tool that acts as molecular scissors, allowing researchers to precisely alter stretches of genetic code. In 2018, scientists from China used mouse stem cells — which they engineered to contain one set of maternal chromosomes — to breed mice pups with two mothers, according to a study published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

To do this, they used CRISPR to snip out genetic instructions from these stem cells and injected them into sex cells from another female mouse, creating an embryo with two sets of maternal DNA. They then transferred the resulting embryo into a surrogate mother.

Of 210 of the embryos implanted in surrogate mothers, only 29 were born. For this study, researchers also produced mice from two fathers — but the offspring only survived a few days after birth.

Technology of tomorrow

Despite early successes in mice, experts caution that many engineering hurdles remain before the technologies of tomorrow allow same-sex human couples to have children.

For instance, human cells require longer periods of cultivation to produce a mature egg, Kevin Doxzen, a biotechnology researcher and a fellow at the World Economic Forum, tells Inverse.

That could increase the risk of unpredicted and potentially risky genetic changes, which could kill a developing fetus in the womb.

More broadly, scientists now suspect that CRISPR can introduce unwanted — and even harmful — edits to the genome, even turning cells cancerous, as suggested by research published over the past few years. “You couldn't do any of these experiments without a lot of really technically sophisticated genetic manipulation,” Albertini says.

Genetic engineering technologies like IVG may also spark a bevy of legal and ethical issues. For one, it isn’t clear whether cell donors should give consent in this context. And the outcome of a large number of unused embryos remains hazy.

Techniques using CRISPR have also bred controversy: In 2019, a Chinese court convicted the infamous scientist He Jiankui after he created the world's first gene-edited babies using CRISPR — violating the country’s research regulations in the process.

“There are policies in place that prevent doing experiments like this on humans.”

Still, these new fertility strategies have a ways to go before they’re researched in people, Doxzen says. “There are policies in place that prevent doing experiments like this on humans, because you would technically be disposing of hundreds — or even thousands — of embryos.”

Despite these limitations, some startups aim to move this research from mice to humans. For example, a California-based company called Conception wants to form human eggs with stem cells sourced from human blood samples, though they’ve been tight-lipped about a specific timeline. (The company declined an interview with Inverse.) “There have been a lot of companies that have said they’re going to make eggs from human stem cells, but nobody has ever come close,” Albertini says.

Beyond allowing same-sex couples to have biological children, IVG may be useful in treating health conditions that can result in infertility, such as Turner's syndrome — where one copy of the X chromosome is missing or partially missing.

Hayashi presented his team’s findings at the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing at the Francis Crick Institute in London in early March — there, he estimated that this technique could be used with humans within a decade, reports The Guardian. Experts like Albertini and Doxzen, meanwhile, don’t think this timeline is realistic.

Still, if researchers can overcome the technical (and ethical) obstacles, genetic engineering technologies like IVG could rewrite the rules of human reproduction — creating previously unimaginable possibilities for queer couples and their children.

The Cusp is a weekly Inverse series that offers a sneak peek at the science and technology that could power our future.