The old National Film Board of Canada headquarters in Montreal, with its smokestack and beige brick facade, was the very image of a film factory. Until it moved to its new offices in 2019, the NFB had the distinctly nondescript aesthetic of a mid-century institutional building, a simple utilitarian look that contrasted sharply with the imaginations let loose within. Set up in 1939 to produce and distribute original Canadian film content, it kick-started numerous careers, stimulated the development of entire sectors of the industry (notably in animation), and served as an incubator for new and emerging technologies. Perhaps most importantly, the NFB has faithfully served the nation by telling our stories, to ourselves and people around the world, for over eight decades.

That might be careening to an end. The NFB eliminated fifty-five jobs in early April, representing about 14 percent of its workforce. Two interactive studios were shuttered earlier this year, and even more jobs were lost last fall when the film board closed regional studios in Edmonton, Halifax, and Winnipeg. These cuts come after decades of austerity budgets. NFB commissioner Claude Joli-Coeur had admitted in a CBC article in 2019 that the film board was operating on far lower budgets than it had in the past. According to a 2022 report by the Canadian Union of Public Employees, the NFB has been underfunded for twenty years at least.

NFB brass are spinning the staff reductions as modernization. They claim the cuts will free up $5 million to reinvest in the film board’s key businesses of documentaries and animation. But typical management rhetoric—do more with less, trim the fat, get smaller before we get bigger—makes little sense in the context of the NFB, an organization whose mandate is, in part, to “create, produce, and distribute distinctive and original audiovisual works that reflect the diverse realities and perspectives of Canadians.” A mandate like that might give one the impression a public film producer would grow with a growing population. But such is not the case in Canada, where politicians pontificate about what makes us culturally distinct yet often steadfastly refuse to adequately fund the arts.

And steadfastly refuse to admit it. In an email response to specific questions about the impact of the cuts over the past twelve months, a spokesperson for Minister of Canadian Heritage Pascale St-Onge described Liberal Party investments in the NFB as “historic,” saying “our consistent investments and support of the National Film Board has strengthened the creation of and access to bold, original films and animation of the highest quality for Canadians.” They continued with “while other political parties threaten to weaken our cultural sector’s vital economic and social impact with cuts, our Liberal government continues to stand up for it.” Finally, they compared the NFB to other “cultural and screen sector organizations coming out of the pandemic” that are now “refocusing their funding to reduce their structural deficit.”

But is the NFB really just another cultural organization, like a film festival or community theatre group, that got knocked down by COVID-19 and is struggling to get back on its feet? Its “structural deficit” isn’t a consequence of audience attrition, increased costs, or declining revenue. It’s a consequence of chronic underfunding—an issue that goes back years, inflicted by Conservative and Liberal budgets alike. Having created around 13,000 original productions and won over 7,000 awards, the NFB should have already amply proven its worth to the Canadian public. Star Wars might not have the Force, animation might not have ever made it past Disney, and we might not have a film industry were it not for the NFB. But in a world where the success of a film producer and distributor is too often exclusively measured in box office sales and merchandising, the NFB can only ever look like a failure.

Reacting to the most recent round of job cuts, the Syndicat général du cinéma et de la télévision (the union representing NFB workers) noted that the film board had, in fact, eliminated eighty positions since the beginning of this year. A deeply concerning number, especially when you consider the NFB had only 381 full-time employees on its payroll last year. In a press release, the union stated job losses were likely higher given the number of silent cuts that had occurred, reflecting the new downsizing trend of “quiet cutting”—eliminating someone’s position and moving them to a less prestigious position, leaving them with fewer responsibilities and lower pay, and, often enough, waiting for them to quit and avoiding the financial liabilities inherent to layoffs. “A true modernization,” said Olivier Lamothe, SGCT president, in a statement, “would be to ensure adequate funding for the NFB to preserve its integrity and protect the craftspeople who work there with all their heart.”

In other words, if the Liberals are indeed making historic investments, then the NFB shouldn’t have to tighten its belt. Indeed, the NFB is also expected to pick up the tab for whatever modernization it is currently undergoing. According to the 2022 CUPE report, the government has refused to absorb the expenses of moving the NFB to its new head office, something that’s cost the film board $1.2 million per year off the top of its budget since 2018 and is likely to continue at least up to 2030.

The closure of the NFB’s interactive studios in Vancouver and Montreal earlier this year didn’t even register in Canada’s mainstream media despite the fact that the studios had operated for fifteen years and were involved in the cutting edge of new media: augmented and virtual reality, interactive and immersive media. The NFB’s statement on the studio closures was rife with political doublespeak—closing the studios would save $3.5 million, the film board said, permitting it to direct $2 million for “innovation” and “audience engagement.” One might wonder what’s more innovative and engaging than immersive, interactive virtual environments. The same press release glossed over the elimination of fourteen full-time positions by indicating a half dozen might be created in the future. The NFB even concluded their announcement of the two studios’ closure with “mission accomplished,” stating that, because the studios had produced 200 works and collaborated with 500 artists, they had fulfilled their mission before passing the baton to the private sector.

The film board’s mandate, however, doesn’t say anything about stimulating the private sector. The NFB is a public service created expressly for societal benefit. It does not have the financial tools that could see it through lean years. It has no equivalent of TV licensing, which helps fund the BBC and has given it some considerable independence, or the Corporation for Public Broadcasting—the organization that funds PBS and NPR in the United States—which receives federal funding but also raises funds through corporate and personal donations and directly from viewers. Moreover, what’s distinctive, original, and introspectively Canadian often doesn’t become commercially viable. Culture and commerce aren’t the same thing. Norman McLaren’s 1952 Neighbours, with its dazzling and pioneering mix of live-action and stop-motion animation, or Alanis Obomsawin’s 1993 documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, which transformed our understanding of the Oka Crisis—who else would have produced these groundbreaking films?

In response to several questions from The Walrus about the future of the film board, Lily Robert, the NFB’s director of communications and public affairs, stated in an email that there is no plan to merge with Telefilm or the CMF, nor to discontinue the NFB’s streaming service. For many of the other questions, it was much the same content as could be found in the official government press releases: saving to reinvest in documentaries and animation, the film board’s bread and butter, was the headline they favoured.

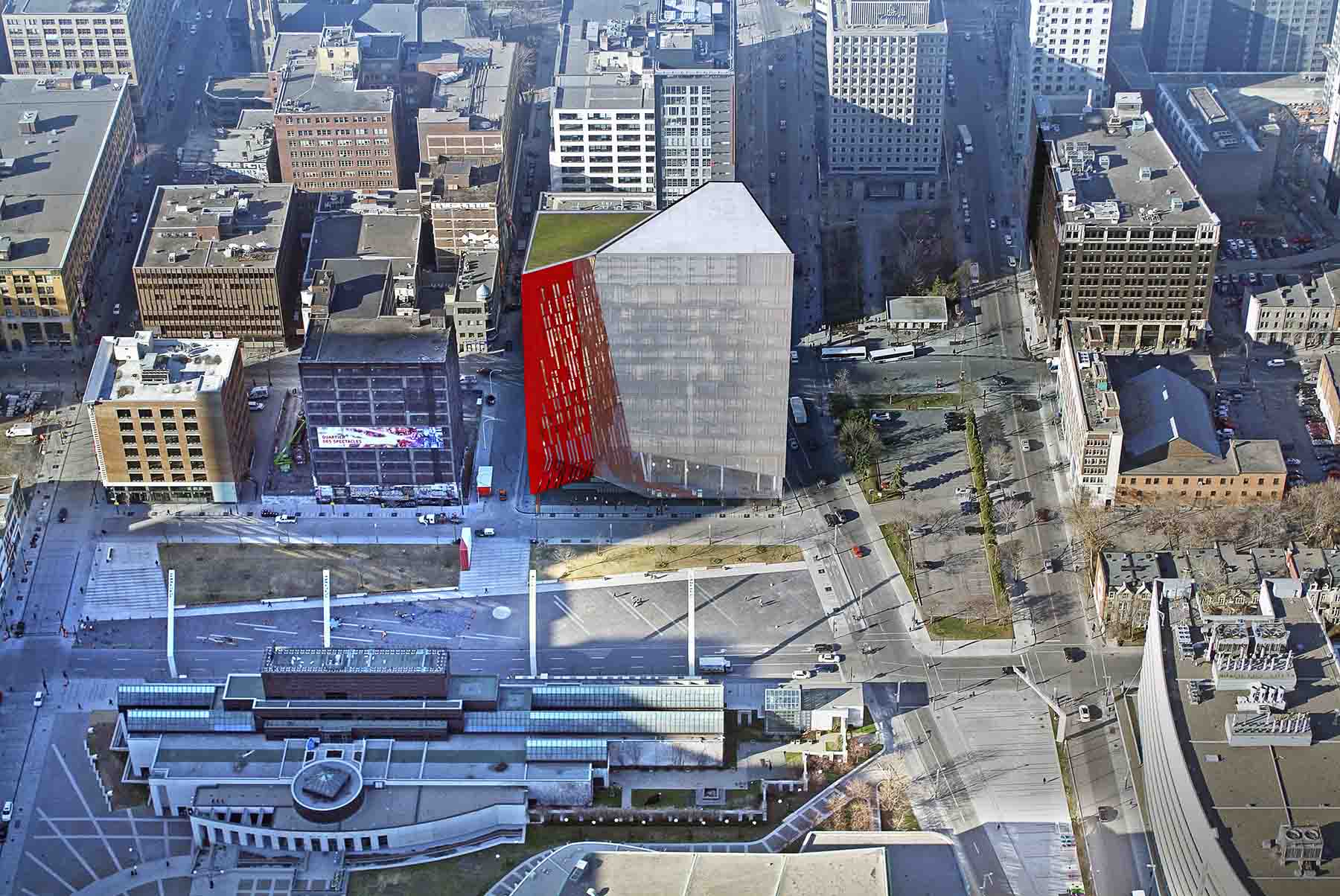

On the edge of Montreal’s urban core, the NFB’s sprawling former campus is slated for residential redevelopment. The NFB’s new office sits on the edge of Montreal’s entertainment district, le Quartier des spectacles. The iconic “seeing man” logo has been affixed to the top-right corner of the building’s eastern facade, but little else identifies it as the home of Canada’s public film producer. It is a small, somewhat irregularly shaped, glass-walled box separated into two triangular buildings by an atrium whose inner walls are painted bright red.

It looks like someone cut a giant heart in two.