What Are Currency Depreciation and Appreciation?

In the foreign exchange market, currency depreciation occurs when the value of one currency falls compared to the value of one or more other currencies. On the flip side, currency appreciation occurs when one currency gains value compared to one or more other currencies.

What Is the Foreign Exchange Market?

The foreign exchange market (also referred to as forex and FX) is where currencies are traded, and as a whole, it is by far the biggest market in the world on a daily trading basis, exceeding the average daily trading turnover in the bond and stock markets. According to the Bank for International Settlements—a financial institution that is controlled by central banks worldwide and serves as their bank—daily turnover on foreign exchange markets exceeded $6 trillion in 2019, the latest year in which data was compiled.

Trading in the forex market affects the relative values of various currencies, and the relative values established by the forex market create the exchange rates at which travelers and other consumers can exchange currencies.

Foreign exchange is an integral part of global business, and reportedly, about 40 percent of the earnings of companies that make up the S&P 500 Index come from overseas. That means these companies have to repatriate money earned in euros, yen, pounds sterling, Swiss francs, Brazilian reais, Canadian dollars, Indian rupees, and other currencies back into U.S. dollars through these foreign exchange markets. When a currency appreciates or depreciates, it can have a large impact on a company’s bottom line.

Why Do Currencies Depreciate and Appreciate?

The value of a nation’s currency typically changes because of events or policies undertaken by that country. A single factor or a combination of factors may contribute to a currency’s change in valuation.

A floating currency is more subject to depreciation or appreciation than one whose rate is fixed to the value of another currency. For example, the Canadian dollar is a floating currency, so the market dictates its value. The value of the Hong Kong dollar, on the other hand, is pegged at a fixed exchange rate to the U.S. dollar.

The following are some of the main factors that can affect various currencies' appreciation and depreciation relative to one another.

Interest Rates

An increase in a country’s interest rates tends to make its currency more valuable. A higher interest rate may lead to higher rates on sovereign debt, making it more attractive to domestic and international investors. A country lowering interest rates, on the other hand, might make its assets less attractive.

Trade

Another prime factor that influences a currency’s direction is a nation’s trade balance. A deficit in the current account, which represents the broadest measure of trade in goods and services, could mean that there’s less demand for the local currency because there are more goods imported than exported. A current account surplus, on the other hand, indicates that a country sells more goods abroad than it imports, and that translates into more demand for the local currency.

Speculation

Investors may sometimes turn to speculation and target a country’s currency for profit. For example, in 1992, George Soros made a profit exceeding a billion dollars when he bet against the British pound, which dropped significantly against the dollar because it was viewed as overvalued at the time.

Politics

A change in a nation’s political future may prompt investors to trade for or against that country’s currency. Uncertainty over leadership may cause the currency to depreciate, while optimism for the nation’s future may lead to appreciation.

Global Influences

Worldwide or international events may cause currencies across countries to depreciate or appreciate. For example, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, nations closed their borders, which resulted in global trade coming to a virtual halt, tourism declining, and people not spending. As a consequence, currencies depreciated.

How to Calculate Depreciation and Appreciation

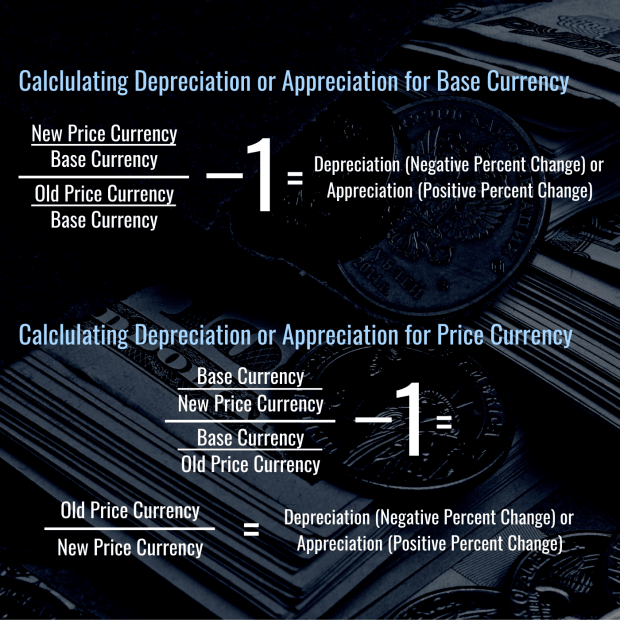

A change in the value of one currency against another is typically expressed as a percentage. When calculating the change in the value of one currency (using another as its benchmark), it’s important to note which is the base currency and which is the price currency.

Calculating Depreciation or Appreciation Using Base Currency

([New Price Currency / Base Currency ] / [Old Price Currency / Base Currency]) — 1 = Depreciation (Negative Percent Change) or Appreciation (Positive Percent Change)

For example, let’s say a U.S. dollar fetches 20 Mexican pesos during trading on a Monday. In this case, the base currency is the U.S. dollar, while the price currency is the Mexican peso. Monday’s exchange rate can be expressed as 20 Mexican pesos per U.S. dollar. The following day, Tuesday, the dollar is quoted at 22 Mexican pesos.

In this equation, the price currency is the numerator, and the base currency, which is represented as 1, is the denominator.

Using the equation above, ([20 / 1] / [22 / 1] ) — 1 = (20 / 22) — 1 = 0.909 — 1 = -0.0909 = -9.1 percent.

That translates to a 9.1 percent depreciation in the Mexican peso compared to the U.S. dollar.

Calculating Depreciation or Appreciation Using Price Currency

([Base Currency / New Price Currency] / [Base Currency / Old Price Currency]) — 1 = (Old Price Currency / New Price Currency) — 1 = Depreciation (Negative Percent Change) or Appreciation (Positive Percent Change)

To measure the dollar’s change to the peso, this formula for the base currency would be used—it is the inverse of the previous formula.

Filling in the Mexican peso as the base currency and U.S. dollar as the price currency, ([1 / 20] / [1 / 22]) — 1 = (22 / 20) — 1 = 1.1 — 1 = 0.1 = 10 percent.

Looked at from this angle, the U.S. dollar appreciated in value by 10 percent compared to the Mexican peso.

Notice that these two results are different. One currency, the Mexican peso, weakened against another currency, the U.S. dollar. But it can also be looked at from the other side—the U.S. dollar strengthened against the Mexican peso.

Note: Technically, a currency’s depreciation cannot exceed 100 percent. Rather than express it in mathematical terms, it is better to phrase it from its original level to its current level. For example, it makes more sense to say that the Mexican peso depreciated to 46 per U.S. dollar from 21 instead of saying it declined by 125 percent.

What Happens When a Nation's Currency Depreciates?

When a country’s currency depreciates, its central bank can intervene in an attempt to prevent the currency from depreciating further. Their main tool in stemming a decline is the use of international reserves, which are typically in U.S. dollars.

Central banks, especially in developing nations with trade surpluses, tend to save dollars as a way to help strengthen their balance sheets because the U.S. dollar is viewed as stable and has been serving as the world’s currency of choice for the past few decades.

If a currency comes under attack from speculation, a country’s central bank could buy back its national currency by selling U.S. dollars in the foreign exchange market. Sometimes, a central bank can use up almost all of its international reserves with disastrous results that leave it with few resources to defend its currency, leaving the country vulnerable to a freefall of depreciation. For countries that have high debt relative to gross domestic product, this can mean risking a pick-up in inflation and defaulting on debt.

How Do Depreciation and Appreciation Affect a Nation’s Economy?

A stronger currency can have upsides as well as downsides for a country. In the U.S., for example, international investors are attracted to American assets, such as real estate, and U.S. government securities due to the strength of the U.S. dollar. At the same time, though, an appreciating currency could make asset prices higher, raising the specter of an acceleration in inflation.

Real-World Examples of Currency Depreciation

Currency depreciation is not an uncommon issue—it has occurred on a large scale in various countries, and in some cases, the consequences were significant.

The U.K

In 1990, the U.K. joined the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), which allowed its currency to be fixed against other European currencies but allowed to trade within a range. In 1992, the British pound was viewed as overvalued and was coming under attack from speculators. The pound sterling decoupled from the ERM and traded freely, but its value depreciated, allowing speculators like George Soros to pocket huge profits. The U.K.’s response to prevent the pound’s sudden depreciation was a steep increase in interest rates and buying its currency in the foreign exchange market.

East Asia

In the lead-up to the 1997–98 East Asian currency crisis, nations such as Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, and South Korea were building up years of deficits in their current accounts. Yet, their currencies remained relatively stable, and their exchange rates traded against the dollar in a narrow range for many years.

The Thai baht was the first currency to come under attack, and the central bank tried to defend the baht by selling dollars from its international reserves until almost all of its reserves were gone and the baht traded to float freely. The baht lost half its value, and depreciation in currencies of other East Asian nations followed. Economies went into recession, marked by high unemployment rates and accelerating inflation. Businesses collapsed as their dollar-based loans became difficult to repay.

Currencies of many countries affected in this contagion have yet to return to their pre-1997 crisis levels, and it took years for some countries to bring back their international reserves to earlier levels. One benefit from their depreciating currencies was that purchasing goods produced in their countries became cheaper, pushing their current accounts into surpluses.

Sri Lanka

In 2022, after years of mismanagement of the country’s finances, a persistent current account deficit, and an unpopular government, Sri Lanka’s rupee depreciated to record levels. In its economic collapse, prices for consumer goods such as gasoline and food skyrocketed.