What is the most important thing a scientist needs? – Lennox, age 6, Leichhardt NSW

Hi Lennox! Thanks for this great question. Unfortunately, there’s not really one simple answer. So I’m going to talk about three important things.

Scientists need to be good at asking questions. They need to be good at investigating the world to find answers to their questions. And they need to keep in mind that no matter how much they know, there’s always more to learn.

Asking questions

Most scientists are inspired by wanting to understand how things in the world work. That means they start by asking questions.

The questions might be driven by curiosity about something amazing in nature, like “Why do stars look like they’re twinkling?” or “Why do these birds have such fancy feathers?” Or they might be driven by wanting to help communities (or even the whole world) with a problem, like “How can we keep this river healthy?” or “What can we do about climate change?”

But all good scientific questions have something in common: they will point scientists towards some sort of investigation they can do to try and find out an answer.

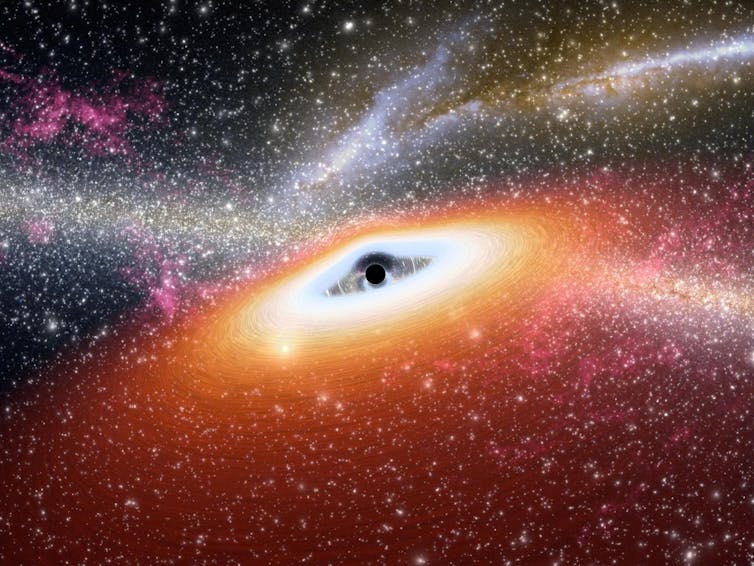

Scientists investigate in many different ways. Some examples are observing how animals behave in the wild, measuring how plants grow over time, doing an experiment in a lab, or using a computer to create a virtual version (called a simulation) of a black hole.

Read more: Curious Kids: can black holes become white holes?

Finding answers

Different scientific questions call for different sorts of answers. Here are some examples (asked by other curious kids!).

Why do onions make you cry? How do ants walk on the ceiling? These questions call for explanations: telling us why or how something works the way it does.

Could octopuses evolve until they take over the world and travel to space? This question calls for some explanation about octopuses and also a prediction about what might (or might not) happen in the future.

How many stars are there in space? This question calls for a number (but it helps if the answer explains a bit, too).

How do scientists investigate the world to find answers? It often takes a lot of training and some creativity. There is a thing called the scientific method which you can think of as a sort of recipe for doing science. It goes like this:

Ask a question

come up with a guess (called a hypothesis) about an answer to your question

do an experiment to test your hypothesis

report what you learned, so others can learn from it too.

This is a good way to do science, and many scientists always follow these steps. But many others don’t. Some scientists do experiments. Some do observations instead, or create models and simulations of the things they want to learn about.

Also, not all scientific projects start with a hypothesis and then test it. Some start with big open-ended questions and investigate them by exploring. There is really no such thing as the scientific method. There is a whole family of scientific methods.

Read more: How many stars are there in space?

There is always more to learn

Becoming a scientist takes a lot of learning. But it is important for scientists to keep in mind they don’t know everything. A fancy name for this is intellectual humility. “Intellectual” has to do with how clever we are, and “humility” has to do with recognising our own limits.

So, “intellectual humility” means being aware that you’ll sometimes get things wrong. It also means listening to other peoples’ ideas rather than just thinking you’re right all the time.

The relationship between science and truth is complicated. Scientists work hard to learn true things about the world. But the things we think are true change over time. A few hundred years ago, people thought that when we get sick it’s because of some sort of poison in the air. Then we learned about bacteria and viruses, and figured out they can make us sick. But we still haven’t figured out everything about how that works.

It’s great to be curious – there’s always more to learn!

Read more: Curious Kids: could octopuses evolve until they take over the world and travel to space?

Emily Parke receives Marsden funding from The Royal Society of New Zealand Te Apārangi.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.