Can black holes become white holes? – Remy, age 9, Wangaratta, Victoria

Hi Remy! Thank you for this great question. The short answer, unfortunately, is no.

White holes are really just something scientists have imagined — they could exist, but we’ve never seen one, or even seen clues that one may exist. For now, they are an idea.

To put it simply, you can imagine a white hole as being a black hole in reverse. So if time was running backwards, black holes would look like white holes. But time doesn’t run in reverse in our universe.

To understand more, let’s start by thinking about how black holes work.

What’s a black hole?

When you drop a tennis ball, it falls to the ground due to what we call gravity. The Earth is very heavy, so it pulls the tennis ball down.

If Earth had more material inside, making it even heavier, gravity would pull on the ball more strongly. The pull would also be stronger if we stood on the surface of a shrunken Earth, which remained as heavy as it is.

Now, imagine we’re deep space explorers and we’ve found something out in space that is both extremely heavy and very small. It pulls very strongly on anything that comes close to it, so we keep our spacecraft a safe distance away.

This mysterious object would pull so powerfully that nothing inside could escape to the outside. A spaceship with the biggest rocket boosters couldn’t escape. Even a laser beam, fired straight out at the speed of light, would not make it to the outside.

This kind of object is a black hole.

Read more: Curious Kids: can Earth be affected by a black hole in the future?

What’s a white hole?

Now imagine we stick around in our spaceship (at a safe distance) and make a movie of this black hole.

As we watch it, we’d never see anything escape the black hole. We would instead see the black hole eat anything that came too close. We get lucky: as we watch, the black hole swallows an entire star!

Our movie, titled “Black hole eats a star” gets a million views online. But now imagine if we played it in reverse. In the backwards movie, we’d see a very heavy, very small object just sitting there – and then, all of a sudden, spit out an entire star!

The object we’re looking at now, which spits everything out and eats nothing, would be called a white hole.

Are there white holes?

We have good evidence from our telescopes that black holes really do exist.

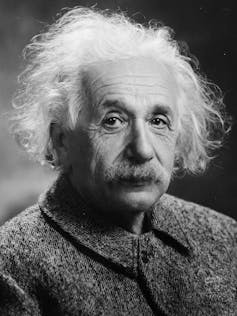

However, we’ve never seen a white hole (which is a shame, because they would be really awesome). The reason astronomers think about white holes at all is because of Albert Einstein – a great scientist who is no longer alive, but if you’ve ever seen him you may remember his crazy hair.

Einstein came up with an excellent idea about gravity, the invisible force that keeps our feet on the ground. His theory describes how black holes work, with their huge gravitational pull.

Einstein’s idea also says white holes are possible. So could our universe actually make a white hole? And could a black hole become a white hole? Probably not. Something can be “possible” as an idea, but also extremely unlikely in real life.

White holes are unlikely because they are an “in reverse” kind of thing. Think of breakfast in reverse: your egg unscrambles itself and jumps out of the pan, back into the shell. It’s possible, but it would mean time had turned itself around and started running backwards.

As best we can see and measure, time in our universe only flows in one direction: forward. So for now, white holes are just an interesting possibility.

Luke Barnes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.