With a new NFL season upon us the trophy hunt begins again; but what about the league's other trophies, the ones with a dark past that people are more reticent to discuss?

Taxidermy conjures up images of mounted deer heads over fireplaces . . . One hardly thinks of sports teams or car manufacturers.

These aren't the shiny ones that teams almost kill each other to win; these are the ones you literally kill to take, celebrating the genocide of another peoples. The trophies I am referring to are the Kansas City Chiefs, the Atlanta Braves, Chicago BlackHawks, Golden State Warriors and countless other teams at all levels of sports. Of course this particular trophy-taking practice isn't reserved just for athletics, but seen in all aspects of business, from brands like Pontiac and Jeep Cherokee to depictions in media.

While the pushback to the use of Indigenous imagery is nothing new, most chalk it up to a disagreement over — or sensitivity to — cultural appropriation. The term has been used to describe when a member of one culture takes elements of another culture to use as an accessory (or repurpose entirely) without accreditation or even going so far as to denigrate its origins as somehow lesser. However, cultural appropriation doesn't capture the full scope of the problem.

Take a musical artist who wears a traditional Indigenous headdress for a performance simply for the aesthetic. This is deemed cultural appropriation, the thoughtless use of and disregard for a mearningful symbol reserved for those who have earned it. But when this act is juxtaposed with the "Chief Wahoo" mascot long used by the team formerly known as the Cleveland Indians or the Kansas City Chiefs players regularly donning helmets adorned with pictures of arrowheads, the adoption of these manufactured symbols that are reproduced over and over again convey far more. And because of that, they cause more damage.

Instead, I propose that these pseudo representations of Indigenous Peoples in professional sports, consumer branding and the entertainment industry aren't cultural appropriation, but actually much closer to a form of trophy taking that I refer to as cultural taxidermy.

What is cultural taxidermy?

You will find few taxidermied bears posed as if it they were nursing cubs or eating berries in a non-threatening manner. That wouldn't make the hunter look very strong.

Let's look at what taxidermy is — a prop meant for display, to be a symbol of the hunter's prowess in conquering the natural world. Depending on the animal, a taxidermist will choose to display it in a specific pose, but typically try to reflect this victorious ideology, especially if it's seen as a so-called fierce beast.

For example, you will find few taxidermied bears posed as if it they were nursing cubs or eating berries in a non-threatening manner. That wouldn't make the hunter look very strong or proficient for having killed it. But is this supposed to be an objective depiction of a bear or is this just one moment of its overall existence that the hunter has posed statically to tell a story about him? Whether it's true the bear rose up ready to attack or the hunter shot it while it was drinking water passively doesn't matter — the bear will be forever frozen in time as the antagonist in the hunter's story. And for those who have never seen a bear, this unjustly perpetuates the idea that bears must all be ruthless killing machines. The hunter's bias is packed into the messaging, and that's what is problematic when it comes to cultural forms of taxidermy.

In U.S. history, we see the origins of this particular cultural practice during the Victorian era. Prominent Indigenous leader and medicine man Geronimo was largely touted as the last Indian warrior in newspapers as he was leading raids against U.S. soldiers, and became a mythical and romanticized figure when he surrendered in 1886. With Geronimo's surrender, newspapers ran front page headlines declaring victory and that the "Indian Wars were over." With the final embers of colonial resistance now stomped into the ground, the West had been won and could officially be considered settled.

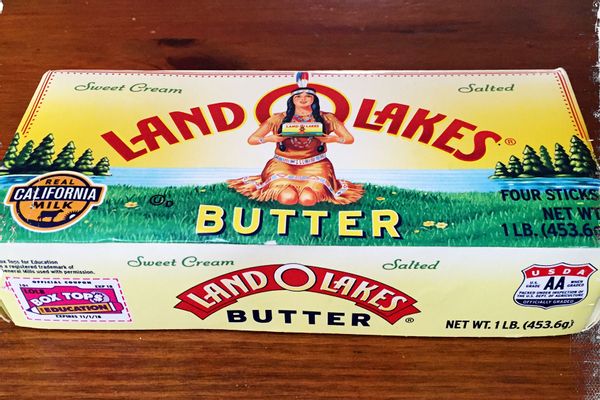

It was around this time we started to see those first examples of cultural taxidermy begin to appear: the Atlanta Braves in 1871, Indian Motorcycles founded in 1899, Pontiac Motor Company in 1907, the Cleveland Indians in 1910, Land o Lakes butter in 1921, the Chicago Blackhawks in 1926 and so on. The practice continued well into the 20th century with the founding of the Golden State Warriors in 1946, the Kansas City Chiefs in 1960 and the Jeep Grand Cherokee in 1974. It also broke into the new millennium with Pontiac's release of the Aztek in 2001. These are just a few of the countless examples that have continued to exist across the different industries in North America.

The cultural taxidermy poses

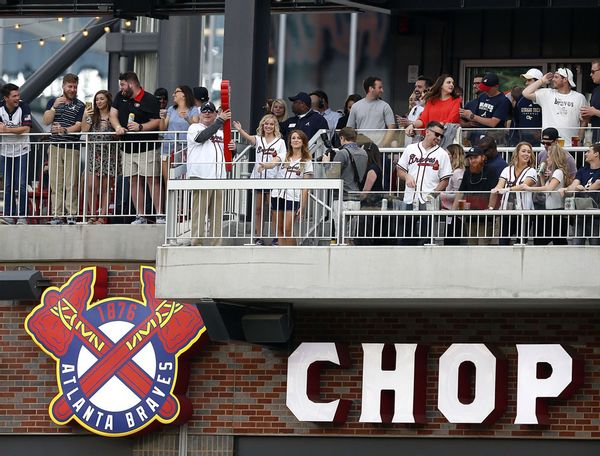

The figure of "The Fierce Warrior" — brave and willing to fight in vain against insurmountable odds — is probably the most familiar as he is often used as a mascot for sports teams like the Goldenstate Warriors, Kansas City Chiefs, Chicago Blackhawks and Atlanta Braves. If sports are a metaphor for war, then the appeal of carrying the figurative heads or weapons of their dead enemies into battle begins to make more sense

"The Honorable Indian" or "Noble Savage" is the figure whose integrity and honor stems from their resolve and pride in commitment to their original way of life despite its newfound obsolescence. You typically will see variations of this trope in movies like "Dances With Wolves" and in vehicle branding as a mark of pride, trust and integrity.

Meanwhile, "The Indian Princess" is usually the Chief's or another high ranking leader's daughter who falls head over moccasins for the settler. Beautiful and submissive, she is grateful to be rescued from her wild life and betrays her own people. We have seen this trope as the logo for Land O' Lakes butter, but we have also seen it in film with white washed stories like that of Pocahontas and Sacagawea.

Seen in movies like "Last of the Mohicans" is the "Wild Lustful Indian" who is so overcome with an unreciprocated ardor when he sees the beauty and innocence of the white woman that he must take her for himself. This was and is a common plot device for the Spaghetti Western and Western genres of film, as is the "Wild, Evil Indian," so bloodthirsty that he will stop at nothing to kill the most vulnerable of innocent settlers. Women, children, the elderly — not even priests are safe from the primal wrath of the bloodthirsty savage.

Some other poses/tropes can also be found in media: "The Stoic Chief," who appears intelligent and hard to negotiate with at first, but is quickly won over by the superior intelligence of the white man; the "Wise Old Indian/Shaman" who's able to heal the settler with an ancient Indian wisdom, perhaps revealing to him some quality about himself that his culture failed to recognize. (We also see this in certain yoga subcultures and new age spiritual movements with the burning of sage in made-up ceremonies, chanting and drumming. Their reasoning for appropriating comes from this culturally taxidermied wise old Indian idea.)

Lastly and probably the most harmful is the stereotypical "Actual or Real Indian." This has unfortunately become the only way to be recognized as an Indigenous person by settlers: wearing long or braided hair, buckskin jackets, feathers and/or beads and war paint.

The effects of cultural taxidermy

Instead, we can see the origins of the mindset that created cultural taxidermy in the mid- to late 19th century, when zoos in America and Europe would often display Indigenous and Black peoples in "wild people from exotic lands'' exhibits. As a prisoner after surrender, Geronimo himself was trotted out at fairs and exhibitions. When we take a moment to consider the connotations of this in tandem with the poses of cultural taxidermy we discussed, we have a pretty good case that settlers did indeed see Indigenous peoples as animals. Therefore, this practice can longer be thought of as simply hyperbole.

Cultural taxidermy has a powerful subtext, particularly when it's flaunted so openly in the public with impunity; it is a tacit statement about power to both the culture displayed and the exhibitor. If you could imagine what a deer might think seeing the head of another deer mounted above the fireplace in your home; do you think it would feel honored or do you think it would feel fearful, angry? Thankfully the deer would likely not understand the context in this scenario, saving everyone the embarrassment. However people do understand context, and although distorted through a colonial lens, Indigenous people do see themselves mounted as colonial trophies, disingenuously and eternally posed as the antagonist in the settler's story of origin.

Each instance of cultural taxidermy put on display echoes the colonial power structure, tantamount to parading enemies of the state through the streets as a reminder to not step out of line again. This is why removing existing examples of cultural taxidermy from the shared cultural landscape needs to be thought of as a priority on par with the ongoing removal of Confederate monuments tacitly celebrating slavery-era politics.

So the next time you see stadiums full of Kansas City Chiefs fans wearing face paint and headdresses or the Atlanta Braves fans doing the "tomahawk chop," ask yourself what they are really saying and to whom.